‘Mouse in Transition’: Detour Into Disney History (Chapter 6)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition will be published every Friday on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Read Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Read Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Read Chapter 3: The Disney Animation Story Crew

Read Chapter 4: And Then There Was…Ken!

Read Chapter 5: The Marathon Meetings of Woolie Reitherman

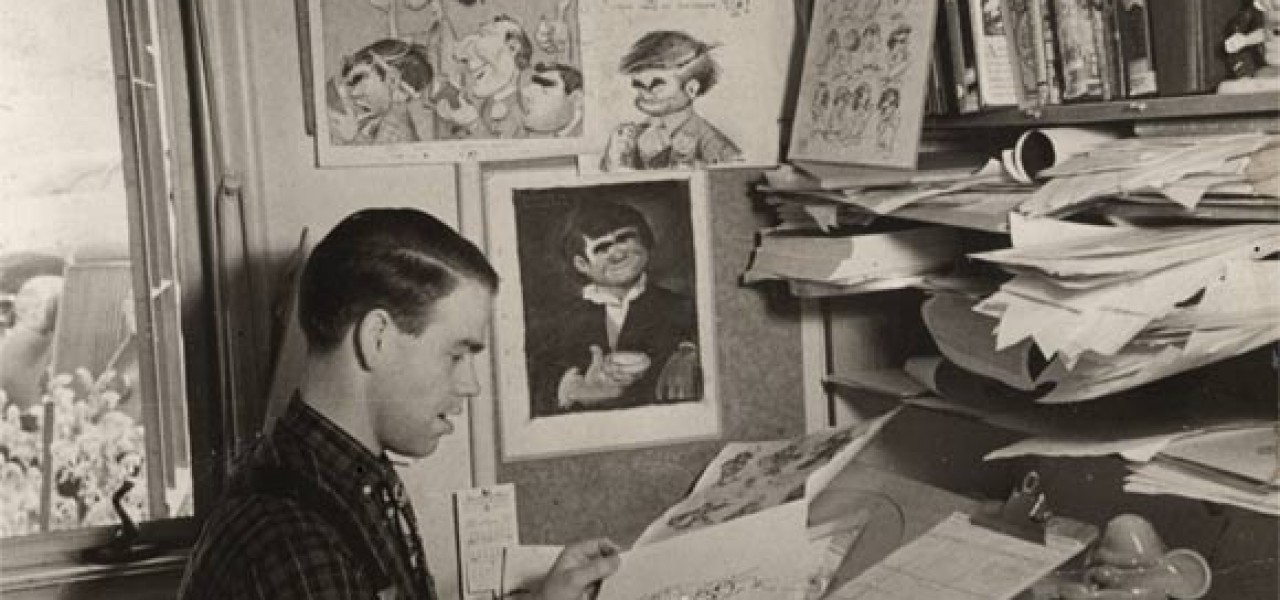

Before I got hired at Disney Features, I sold a few magazine articles and developed a love of writing for print, where there was nothing between writer and reader but words on a page. When I became a Disney employee, I realized I was surrounded by animation veterans with vivid memories of the rambunctious days at the old Hyperion studio, and the creative struggles that went into making Snow White, Pinocchio, and the other early features. Talking to older Mouse House staffers, it dawned on me they could provide great source material for articles.

So with visions of magazine sales glowing in my head, I commenced interviewing the old-timers. Guys that had been there in the thirties on the shorts. Guys that had worked on early features. Their stories and reminiscences threw open windows to a time of smaller, more personal movie-making, when the studio’s founder worked alongside his employees, and the movie world was several clicks less corporate.

I started researching and writing an article about Pinocchio, and contacted Ward Kimball, who had been a supervising animator on the feature. Ward had retired from Disney a few years before, but he was happy to talk, and invited me out to his San Gabriel home, providing me with a tour of his backyard railroad and sheds filled with Disney memorabilia before sitting down with me in his big, sun-washed living room to talk about life at Walt Disney Productions and the trials and tribulations of creating the studio’s second animated feature:

Pinocchio was the first picture where I operated as an animation supervisor. Walt began to take the older, or more talented, or whatever you want to call them animators and make what he called animation supervisors. Maybe two or three of us would go on a picture early—try to take the story sketches and develop a character, draw a character that would work in animation. Lots of times, a story sketch wouldn’t work.

But Pinocchio was no soft touch. In fact, I thought it was harder for everybody than Snow White. We finished Snow White and we said, “Ha. We know how to do features!” And everybody went into Pinocchio with this great load of confidence. Boy, six months later we found out, and Walt found that what you learn in one picture doesn’t necessarily work on the next picture.

The cricket had been drawn like a little black grasshopper, and the problem there was getting a character that Walt would accept. Now, that was a tough job because like I tell everybody, the cricket looked like a cockroach. So each time I’d go up there, Walt would kind of frown and say, “He’s not cute enough,” or something.

So by a process of elimination, I dropped all the cockroach stuff so what we had was a little man, with a cut-away coat, which I suppose you could call wings, the way they come to a point in back, but there they stop. There’s a collar, top hat, and umbrella, and his face is an egg with cheeks. No ears, two lines on top, reminiscent of the feelers, and his nose. You couldn’t put on anything that looked like nostrils or holes or things that looked ugly.

And finally we got this abstraction, a cute symbol they called a cricket. He can’t be anything else, and he’s small. That’s one thing you can say about him: he’s not a three-foot mouse like Mickey…

I carved out a lengthy piece from interviews with animator Eric Larson, background artist Claude Coats, and my former boss Ken Anderson, then on the verge of retirement. Now that I wasn’t working for him, Ken had morphed back into Mr. Friendly, reminiscing about his time on Pinocchio:

I kept a notebook at that time of camera angles and moves from live-action pictures like Anthony Adverse. Walt took a look at the notebook and liked it. He had others start taking notes, too. He was always aiming at exceeding the limitations of the medium, though we never heard it expressed in so many words.

In those big down shots of the town at the beginning of Pinocchio, our layout supervisor Charles Philippi wanted an eagle’s eye view of the town. To get the amount of detail we needed, the scene had to be painted six feet wide and six feet long.

But the most difficult multi-plane shot in terms of design and layout was far from the most spectacular of the film. It’s where Pinocchio is locked in the bird cage in Stromboli’s wagon, and the wagon is moving. You had a great number of levels. There were the swinging bars of the cage, and that cage had two levels, front and back. Pinocchio was inside, responding to the pull of gravity. The problems of proper registration was tremendous. On top of that, you had swinging puppets in the foreground and light coming in the window with the moon shining on the farthest level back. The moon was held while the other things were moving and swinging. The light ray of the blue fairy had to be airbrushed through the window. The final result looks natural, but planning all the effects was every complicated. And expensive.

When I sifted through all the information the veterans had provided and finally finished the piece, I sent the results off to Film Comment magazine. The editors there surprised me by immediately buying it. Excited by this success, I quickly wrote an article about Dumbo. That effort failed to arouse interest from any magazine or newspaper inside the continental United States.

I was puzzling over what to do next when the Disney publicity department phoned to tell me that Viking Press needed several thousand words of text on the making of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs for a coffeetable art book they were publishing, and would I be interested in writing the chapter?

“When does Viking want it?” I asked.

“In eight days. They’ve got an insane press deadline.”

“How much are they paying?”

“Twelve hundred dollars.”

“Sure, I can do that,” I said. For twelve hundred dollars, I would have hand-copied all the books of the New Testament.

So I plunged in. I had never interviewed so many people so fast, nor typed so many pages in such a short span of time. I worked on dialogue and gags for Fox and the Hound during the day, then went home and wrestled with book prose late into the night.

I was inordinately proud when I turned in the copy for The Making of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs a day early, and prouder still when I got the check for doing it from the Disney publicity department. But I had another emotion altogether when, months later, the book came out and I read a review of my work from animation expert and historian Mike Barrier in Funnyworld:

This is a surprisingly thin piece, considering how much research material is available in the Disney Archives. … Hulett seems to have relied mostly on interviews with a few of the people who worked on the film, and this has led him to include a few statements that are at least questionable.

…

Hulett, in explaining why the live-action film for Snow White and the Prince had to be traced, rather than blown up as Photostats as guides for the animators, says that there were no photographic frame blowups in the mid-thirties. That is simply wrong.

I was cut to the marrow when I read Barrier’s indictment, and I went steaming down to Pete Young’s office for some moral support and brotherly love. I showed him Barrier’s article and whined, “This guy lacerated me, Pete. So maybe he’s right that I got a couple of things wrong, but …”

“A couple?”

“Okay, maybe more than a couple. But geez, I only had eight days to write the thing!”

“You got paid, didn’t you?” Pete smirked. “Twelve hundred bucks?”

“Sure, but …”

“So if you feel bad about the review, why don’t you write Mike Barrier a letter and tell him: ‘Sure the piece is lousy, but I only had eight days to write it.’ I’m sure he’ll totally understand.”

I felt my face grow hot. I went skulking out of Pete’s office and climbed the stairs back to my own, feeling like a horse’s backside. Brooding in my office, I decided I would take a break from magazine and book writing and refocus on cartoon work.

Nobody fact-checked dialogue for foxes, owls and badgers.

.png)