‘Manifest 99’ And The New World Of Animating For VR

There’s all kinds of challenges now open to animators; one of the newest is animating for vr experiences. The big difference, of course, from linear-based narrative projects is that in vr, the viewer can look almost anywhere, and that means animating things that might not even be in the center of attention.

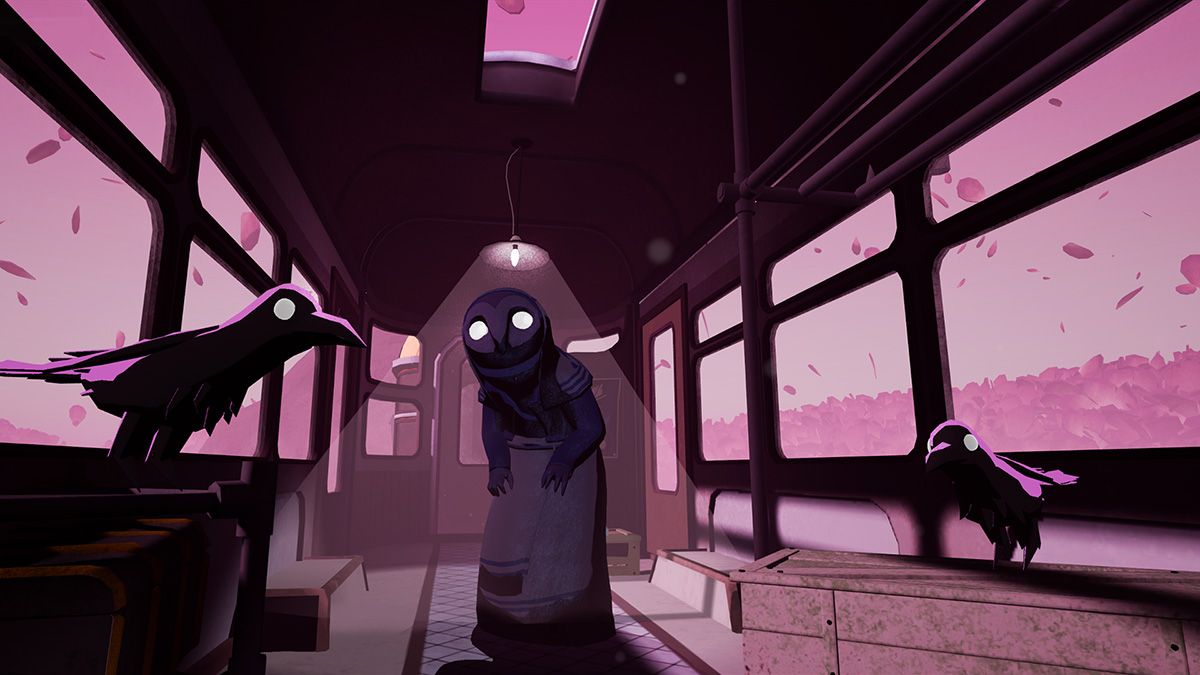

It’s something Flight School Studio – an outfit started by Reel FX Animation and former Moonbot Studios artists – had to comprehend for its debut project launched last year, an interactive vr experience called Manifest 99. In it, viewers follow an eerie tale about redemption in the afterlife while aboard a train and engaged with a number of mysterious animal travel companions.

The painterly Manifest 99, which was developed for the Playstation VR, Oculus, and Vive platforms, was this year nominated for an Emmy Award for Outstanding Interactive Media – Original Daytime Program or Series. Cartoon Brew asked lead animator John Durbin and animator Andrew Stovesand about what it meant to animate for vr while working on the experience.

So, what are the big differences in animating for a vr project than for a traditional narrative one? Durbin told Cartoon Brew that there are obvious similarities – you still tend to work in creative content tools such as Autodesk’s Maya. But the main differences come about in terms of not thinking so much about ‘shots.’ “It kind of changes the way you do staging,” he said. “There’s not really a composition of a shot. You don’t work with silhouettes the same, it’s not like you can lock in nice poses. So you’re kind of challenged by what you’ve learned are the principles of animation.”

Those things represent some of the overall challenges of animation for vr, but there are practical considerations, too. Although vr is essentially a 360 degree experience, that’s not necessarily how animation for vr can be approached. For Manifest 99, Flight School’s team essentially worked normally inside Maya on a flat 2D screen, then consulted with a team of developers working in Unreal Engine for the interactive ‘gaze’ elements of the experience, and then had to review animated sequences separately with vr goggles on. (At one point during the project, the team also tested a way of working in Maya through vr goggles).

“As an animator working with your camera, you playblast it, and that’s what it looks like,” noted Durbin. “In vr, you’re still playblasting and looking at your work, but then you put the headset on and look at it, and it might be completely different! [It might be] too close, too far, and the scale is not right. It’s just such a different and immersive world when you’re in there.”

Stovesand said he had a similar experience working day-to-day on Manifest 99. “I’d think it looked pretty cool from my locked camera Maya angle, but [you] put that headset on and then you get in the world and it’s like, ‘Oh, you could refine that.’ Every time it was eye-opening in a different way. Say, the environment, you wouldn’t think something would be such a huge distraction because of animation.”

One example of where this occurred is in a scene involving a bear. The animators had provided motion in Maya but upon viewing in vr goggles found that the focal length would change a little, and thus, the impact of the bear in the scene was not as great. The solution, apart from adjusting staging and camera placement, was also to, according to Durbin, “crank everything up,” including the bear’s breathing, to add to the impact.

Asked what advice they have to give to any animators thinking of transferring to interactive vr experiences or vr games, Durbin says, “If you’re already working in Maya then you can do this.”

Stovesand adds that animating in vr is about somewhat abandoning the usual approach of perfecting poses and silhouettes. “You can’t be too precious with it,” he said. “It was almost good in a way to have a lot of work, try to knock something out, not overdo it, get it to a good spot, and move onto something else. Other people could check it out and decide whether to come back to it. You upgrade it, get it working better, work on something else, and come back to it. It’s not a film shoot where you have two weeks on this three second shot and you tear it apart down to the eyelash. It’s a different beast in that way, working in vr.”