De-mystifying VFX Bidding And Budgeting: An Insider’s View Into The Process

Amongst the many mysteries of movie magic – that is, how the imagery gets from idea to screen – one elusive part of the process regularly remains somewhat of a mystery: vfx bidding and budgeting.

Historically, the process behind bidding vfx shots has tended to be carried out without too many standardized practices. Vfx shots can can change dramatically over production, but bids don’t always change with them. It’s also a process that can leave vfx studios working in unprofitable ways when their costs of production go over their bids.

To help get a handle on how vfx bidding works, Cartoon Brew got an insider’s view from experienced visual effects supervisor and producer Mark Russell, whose credits include A.I, Minority Report, Tower Heist, The Wolf of Wall Street, and The Promise. He is currently visual effects supervisor on the upcoming films Motherless Brooklyn and Triple Frontier. Here is his film vfx bidding breakdown.

Step 1. An internal vfx estimate

The first thing that generally happens on any film containing vfx is an ‘internal vfx estimate’, observes Russell, noting that his overview of bidding here relates to scenarios where he has already been brought on as the production-side vfx supervisor. “The internal estimate is something that is either done at the studio by simply reading the script, or if there is a vfx supervisor or producer involved, it is something that we would do.”

At this stage, the estimate is only a cursory pass at attempting to identify all of the potential vfx work in a project. It’s here where the vfx production team will try to include every single thing that could be a visual effect, unless there’s been some other decision already that the shot will be achieved in a different way.

“Oftentimes, I will make the initial vfx budget without any input from the creative team, which is always a challenge because there are so many variables in any film,” said Russell. “You are forced to make assumptions based on previous experience and really try to account for everything. It usually comes down to the type and quantity of shots, assets and extra materials, and tools that are needed to complete the project. I rarely will go into detail about the hours and the minutiae of things actually needed to complete a shot – better to leave that to the [vfx] facilities.”

Step 2. Building a bid package

After the internal estimate is put together, Russell says he tends to be able to receive enough creative input from various sources to build a bidding package for vendors. The bidding package may go to various visual effects companies and can include the script (or part thereof), any storyboards or previs, and the breakdown of anticipated vfx shots in the film, or possibly just a sequence or series of sequences.

A relatively common approach in the industry is to divide the shots up by complexity (such as easy, medium, and hard – all of which might change in complexity over the course of production on the proeject).

The vfx studios are invited to make their bids on these shots, and the vfx producer will look to compare those bids in deciding which shots to award to which facility. One thing to point out here: the bid packages can sometimes even not go out until principal photography has finished, but in big visual effects-driven films, vendors need time to ramp up on asset creation and R&D. This means you might need to get bid packages sorted out before principal photography is over, and keep refining as you move into post-production. As a result, there can often be a number of stages that shots can go through in terms of the bidding process (often accompanied with detailed conference calls).

“From my perspective,” said Russell, “it is pretty easy to tell which shots are going to require more time and attention, and I try to communicate that to the vendors as clearly as possible. I will often break a sequence down by how many hard, medium, and easy shots I think there will be and I will estimate accordingly. I really leave it to the vendors to break down the man days and labor costs to go with that.”

At this stage, Russell also adds that including artwork to accompany the bidding material is a must. “Otherwise,” he says, “your numbers and methodologies are going to be all over the place. Previs can be really helpful, if you have a director who will either actively participate in its creation or at least use it. If not, it can be a waste of time, energy, and money.”

Step 3. Getting back the bid

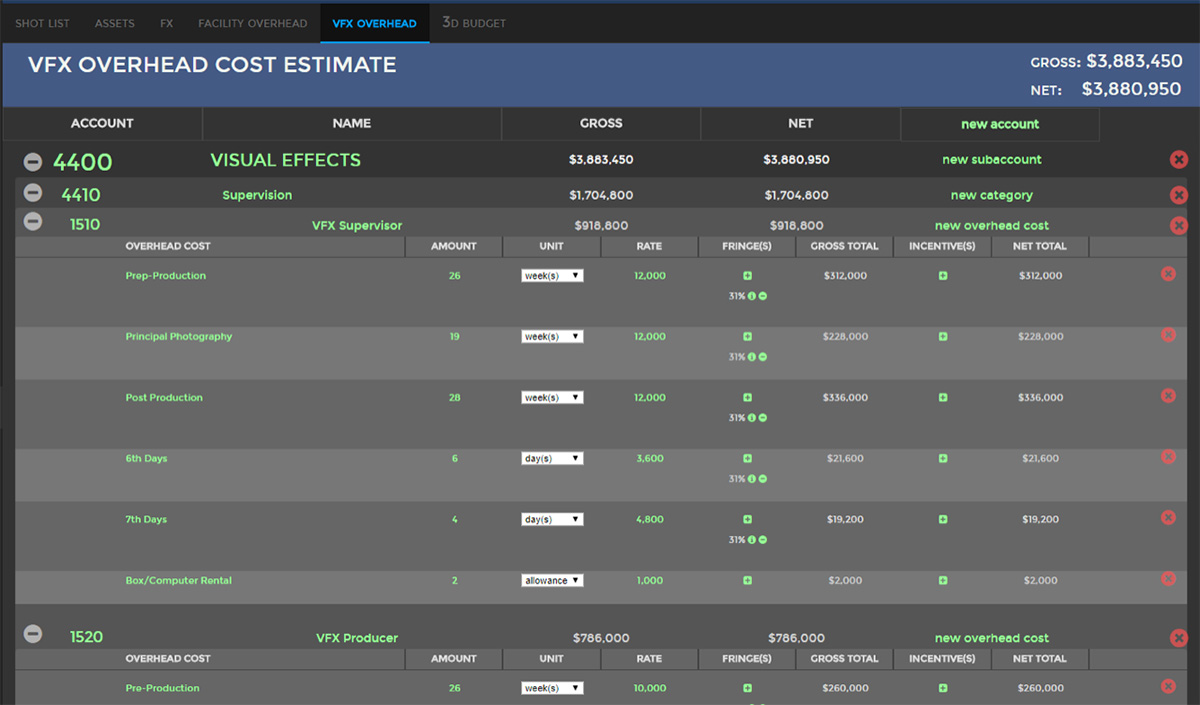

On the vendor side, a vfx bid can be a detailed process. Using what are largely old-fashioned spreadsheets (although new tools such as Curó have started becoming available), the vendor will go through each shot and typically work out the number of artist hours that are involved, based on what tasks might be required, for example, matchmoving, roto, animation, compositing, etc.

“The vfx studio will deliver back an estimate of the costs to complete the work from their facility,” said Russell. “This will often include a proposed creative team and facility location, if bidding a multinational company.”

Here, it’s really experience that comes into play with how much various shots should cost. Bidding on a show has sometimes been described as a ‘dark art,’ and often depends on several factors such as the capabilities of the vfx studio, previous relationships, the project as a whole, tax incentives, and future capacity.

“For me,” suggested Russell, “it’s a combination of a good but fair price and seeing an awareness of the nuance of the project. It’s very important to find the right vendors for any job, and that includes ones with a true understanding of the scope and scale of the work, not only the creative ability to pull it off.

“Oftentimes, if a facility comes back with a bid that is either too high or too low, it tells me that they don’t have the same understanding of the work that I do. So that brings another round of phone calls and bids.”

Step 4. Awarding the bid, and the process of re-bidding

The winning bid is typically confirmed with a contract that spells out the specific requirements and dates for turnovers when the vfx shops will receive the photographic elements from the film studio. (Remember, there can be multiple turnovers and multiple re-bids because some vfx studios might start even before principal photography, or might come onto the project right at the end.)

“I have never been on a project that ended up exactly as bid, even the ones where the bids were based on actual photography,” noted Russell. “There is always a period of reconciliation with the vfx studios about the estimated work and the actual work. Usually, once the actual shots are turned over to the facility, we will receive a reconciliation bid that attempts to put the two straight. This is not an easy task because often the bid work has evolved into something different and tracking bid shots to actual shots can be confusing.

“There is usually a dialogue back and forth about the complexity of specific shots versus what was in the original bid document and then there’s a compromise that most everyone can live with. Then that gets presented back to the creative team and tracked.”

Step 5. Tracking bids

Tracking bids, from a vfx vendor perspective, is obviously an important part of comparing the bid costs to the actual costs of production. Most vfx producers use a spreadsheet, file database, or piece of software to keep an eye on the progress of bids and shots (Shotgun and ftrack are examples of these).

“As shows get bigger, this can be a full time job in itself,” noted Russell. “I have tried myriad ways to keep track of both the shot progress and the costs, but I have yet to find a great solution. Most anyone who has worked in vfx for more than a few projects has a Filemaker Pro database that was built by someone from a previous job, and it has been adapted and changed and bloated from one job to the next. It usually gets the job done.”

Why vfx bidding and budgeting is so tricky

The process of vfx bidding has come under some criticism in recent years, for several reasons. There’s a general lack of consistency in the process, for one. Changes made to story or the edit and to the demands of the shot during production make it hard to sometimes accurately bid. Other common problems are fixed bids, which don’t allow any flexibility in shot changes, and under-bidding, where studios make low bids that may not be profitable this time around, but are aimed at getting a foothold with that client and securing work into the future.

“It’s a tricky process,” said Russell, “because often times the vfx budget is dictated by the producers or studio without regard for the complexity and quantity of the work. We are often asked to come in at or below a certain number before we even get started. On some projects, that restraint works really well, as it forces decisions to be made early about where to spend your money, but more often we are forced to trim a budget in order to get a ‘green light.’ Then once the shoot is underway, the vfx budget balloons back to where you thought it would be initially. Then vfx gets blamed for a bad estimate.

“The same situation can sometimes be true for facilities, often a company will underbid a show in order to get the job, and then once the shots start turning over, the complexities are suddenly more significant than originally stated.”

So, what are some of the things Russell thinks could help improve vfx bidding and budgeting? He says there’s certainly scope for a more transparent system where vfx work is bid based on the actual time spent, as opposed to a per-shot cost.

“I think it would make much more sense to estimate and track work based on the evolution of the tasks and the time and personnel required to complete the work,” Russell said. “I think it would be more fair to the facilities and I think it would give the filmmakers a more clear idea for where the money was going. Most every other department on a film is paid by the time they spend working, but because vfx is largely outsourced and a little more abstract, we have fallen into a system that doesn’t really help anyone.

“A good vfx producer will protect the filmmakers, the studio and the vendors so that everyone knows what is expected and how much it will cost. If scope changes or things become more complicated, then the budgets should really rise to the occasion.”

Image at top courtesy of visual effects supervisor and director Victor Perez from his short film, “Echo.”