The CG Actors in ‘Logan’ You Never Knew Were There

When Rogue One was released late last year, it ignited a new discussion about the digital resurrection of deceased actors, in that case, Peter Cushing as Grand Moff Tarkin, and it sparked debate about the role of digital actors in filmmaking.

That debate is likely to continue in several other films this year, most recently with the creation of a digital double for Hugh Jackman and a new mutant Laura (Dafne Keen) for a few scenes in Logan.

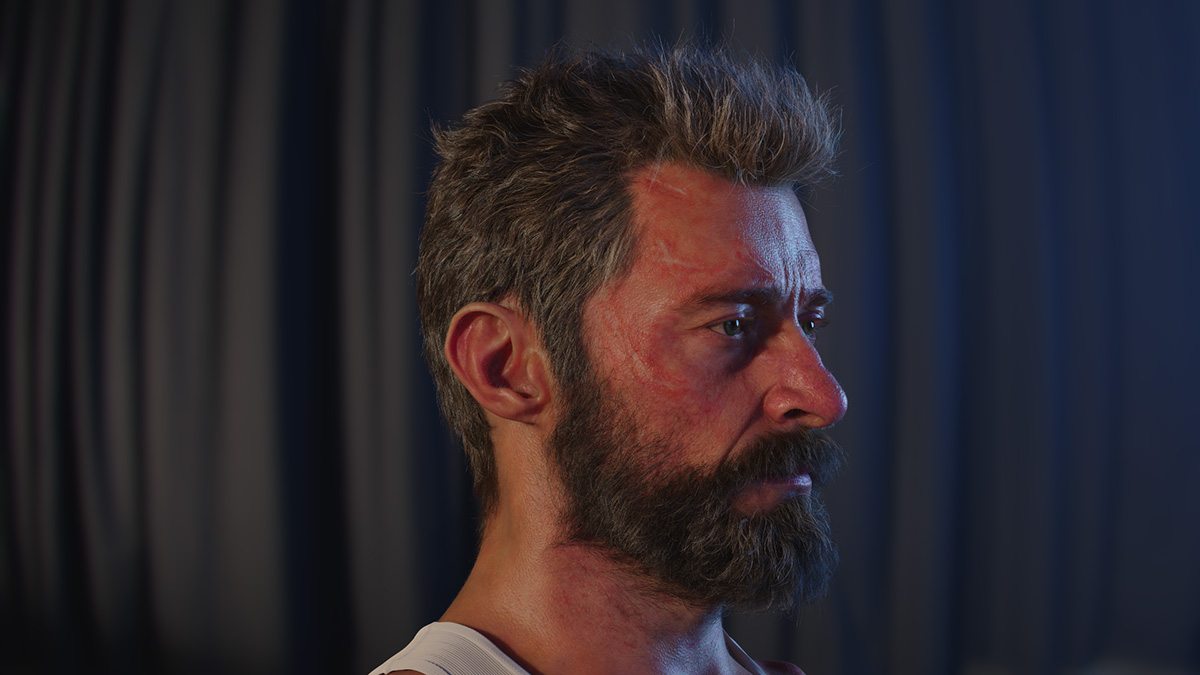

In the film, which is James Mangold’s newest entry into the X-Men and Wolverine franchises, a key story point has Hugh Jackman’s lead character discover the existence of an artificial mutant with his DNA, and with the accompanying healing powers and adamantium claws. This meant Jackman would be appearing in scenes as both Logan and X-24. Other scenes, mostly action ones, also made use of digital Logan head replacement, and a digital Laura.

While Hollywood has been relying on digital doubles for many years, the work in Logan is particularly seamless, even if the scenes are relatively brief and do not involve an avatar delivering any dialogue. It’s perhaps another example of where things are headed with digital actors and how they can be used to help tell the stories directors are wanting to tell. Cartoon Brew sat down with the studio behind the digital Hugh Jackmans and Laura, Image Engine in Vancouver, who worked under overall vfx supervisor Chas Jarrett, to discuss how the the cg ‘digi-doubles’ were brought to life.

After being given the task of re-creating cg heads for Keen and Jackman, Image Engine’s team immediately knew what it was up for. “Everyone knows Logan, for instance, and that’s the biggest challenge,” Image Engine visual effects supervisor Martyn Culpitt told Cartoon Brew. “We’re literally looking at a real Hugh and a digital Hugh side by side in some shots.”

The studio had completed plenty of digital human-type work before, but mostly as either human-esque creatures or as cg stunt doubles – never full-frame actors intended to be indistinguishable from the real actor. That meant Image Engine had to ramp up on their digital human pipeline, while also capitalizing on work they’d previously done in the area. “We basically had to build the whole system from scratch,” said Culpitt.

Breaking down the process

Here’s how the digital Hugh Jackman – as both X-24 and as Logan – and digital Dafne Keen were achieved, from planning the live-action on-set shoot, to filming it, to the special scans made of the actors, to the facial rigging and animation, and the final rendering and compositing work involved. In addition, the studio engaged in de-ageing visual effects for some of the Jackman/Jackman shots, in which footage of the actor would be augmented to make him look like the younger X-24.

1. Planning

Before embarking on the use of digital head replacements, in particular for the Logan and X-24 characters, overall visual effects supervisor Chas Jarrett engaged previs studio Halon to animate a series of scenes in which multiple Jackmans would appear.

“This would give Chas and James Mangold a gauge for how shot choices would impact the shoot schedule and vfx,” noted Halon previs supervisor Clint Reagan. “By having an X-24 sneaking around a generic hallway and getting surprised and attacked by Logan, we were able to illustrate in a cut various situations that might be faced.”

2. The shoot

A few different methodologies were then employed during live action filming to realize shots that would have digital face and head replacements. Stand-in actors wore dots on their heads, for example. This occurred for scenes of Keen’s stunt doubles engaged in fighting, and a sequence inside Logan’s limousine as he is attempting to flee.

For a staircase scene in which Logan encounters X-24 for the first time, Jackman performed the role of Logan at the bottom of the stairs while a stunt double played X-24. A reference plate, shot later, was also made of Jackman doing X-24’s movements in his X-24 make-up — this would be used to test the correct lighting on the final cg head. That particular shot, like all the digital head replacements, required careful match-moving and tracking by the team at Image Engine, especially as the stunt double’s physicality was different to that of Jackman.

What was not utilized, however, was any kind of on-set facial performance capture (with calibrated marker dots or a camera targeted at the face), partly because of time on-set and because the digital replacements would not be speaking. Some tracking dots were employed on the stand-ins and stunt doubles for match moving purposes.

3. Getting scanned

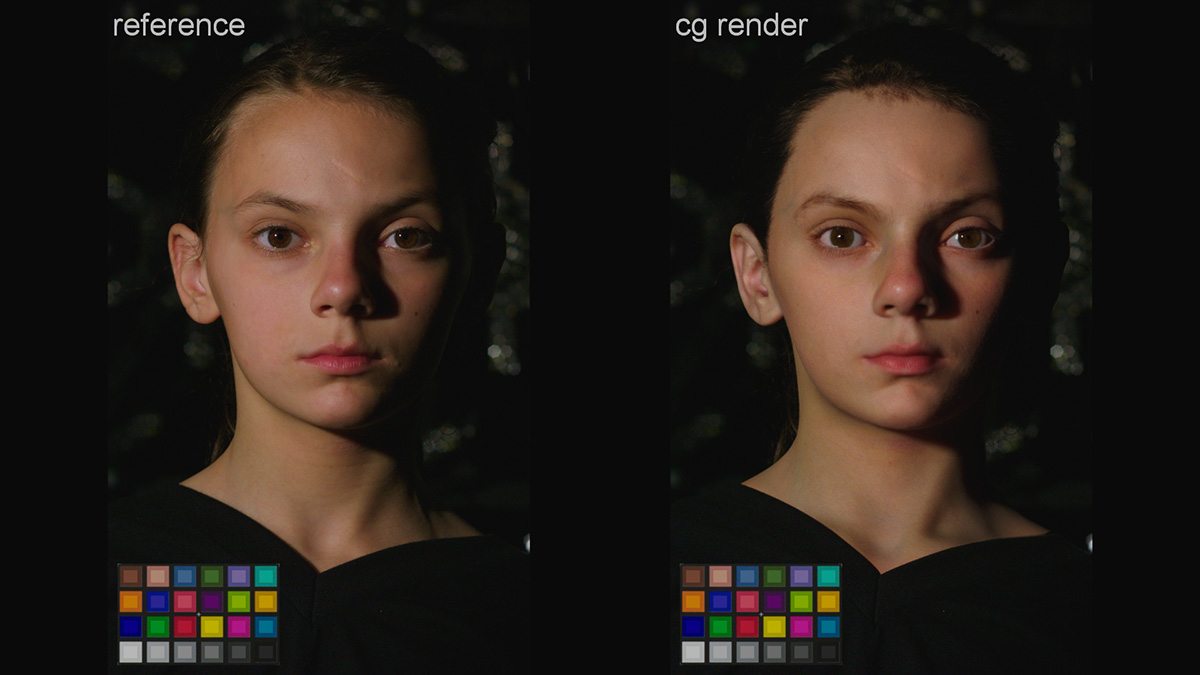

The filmmakers then took advantage of years of research into image-based lighting and the crafting of photoreal virtual humans at the University of Southern California Institute for Creative Technologies (USC ICT) to acquire scans of Jackman and Keen’s face (a photogrammetry rig was also used to acquire full body proportions and textures).

The facial scans of the actors were conducted inside the latest incarnation of USC ICT’s light stage, where multiple lighting conditions can be replicated while an actor performs different Facial Action Coding System (FACS) face shapes – 64 in total. “The idea,” explained Culpitt, “is that we can move between those shapes so it would actually look like our digital actor was moving and emoting.”

Interestingly, Jackman was asked to shave his trademark Wolverine hair and mutton chops for the light stage procedure to help scan as much skin detail as possible. “The reason we did that is then we’d get all the pore detail on his chin and be able to see his mouth and chin shape,” said Culpitt.

Out of the scans, Image Engine received raw photographs of Jackman and Keen from multiple angles, plus cg models of the actors in each FACS pose, and different lighting passes (reflectance, diffuse, etc) for each model.

The raw face photography also matched accurately to those models. “This was actually really helpful to us,” noted Image Engine compositing supervisor Daniel Elophe. “We used it also for the X-24 de-ageing work. We would smooth out the skin, remove all the wrinkles and complexion stuff, and then we would actually take the model of Hugh’s head which had all the pore details and basically multiply it back into his face to get all that detail back.”

4. Building the head

Having the light stage data was still just the beginning for Image Engine, which then had to rig the facial structure and features of their digital actors to animate them. Although the cg characters would not be delivering lines, there remained a need to craft the head as accurately as possible.

“We have a modular rigging system that lets us build each component and then we use a script to build the entire rig at the end,” explained Image Engine cg supervisor Yuta Shimizu. “We had to come up with a way, too, for the animator to iterate many, many times a day but also be able to see almost final quality before rendering.”

5. Facial animation

The fidelity of the light stage captures and Image Engine’s model meant that the vfx team had an accurate representation of each actor. They also had tools to solve hair, in this case, the hair tool Yeti. But one of the challenges the studio found in animating the face was maintaining the ‘look’ of the actor from pose to pose.

“When you go in between the poses, sometimes from different camera angles, it just didn’t look like Hugh or Dafne,” said Culpitt. “So we were literally changing, sculpting, and adjusting animation to make it look like him on every shot.”

Keen’s face was particularly challenging because she had to make wide-ranging expressions while she is attacking her foes. “You’d get a render that would have non-motion blur and you’re like, ‘Oh that’s Laura,’ and you’d get a render with motion blur and you’re like, ‘That’s the scariest thing I’ve ever seen!’ said Elophe.

In the end, solving the eyes for their digital actors would prove to be one of the biggest things that made the shots work or not work (arguably because people are just so used to looking into other people’s eyes and can instantly recognize that feeling of the ‘Uncanny Valley’).

“We were actually refracting light into the eyes properly by building a lens that would mimic what’s happening,” outlined Culpitt. “Without it, it just feels dead. You get on the outside of the lens the proper specular reflections and light play, and that made a huge difference.”

6. Final touches

Lighting the cg actors was handled using Image Engine’s proprietary, and open source, Gaffer toolset. “We created a lighting template that let our artists do a whole bunch of iterations, which let them review things creatively right through animation into rendering,” said Shimizu.

The studio adopted Solid Angle’s ray tracing Arnold renderer for the project which aided in achieving the right level of skin shading and sub-surface scattering on the faces. They also implemented a system via the production management software Shotgun to deliver the right cg model at render time to accomodate the multiple states each cg head and body had to be in, depending on how much damage and injuries were necessary. “Sometimes the shirt is ripped, or there’s blood here, a scar there, or a different hair style,” explained Shimizu.

The state of digital actors

Unlike the cg Peter Cushing in Rogue One, the digital Hugh Jackmans and digital Dafne Keen in Logan would certainly not be considered the main performers. However, the work by Image Engine does showcase what is possible right now in entertainment – see also Framestore’s recent work on a digital Benedict Cumberbatch in Doctor Strange.

Having digital forms of their actors offers filmmakers more choices in getting their desired shots, especially if they involve elaborate stunts. Another obvious benefit of a photorealistic cg stand-in might be where an actor is simply not available for a shoot or re-shoot. Such sleight of hand already happens in terms of clever editing and compositing, but with a full-frame digital head, the performance can perhaps be controlled or more fully realized.

In any case, even if possible, the advent of cg actors is not trivial. It requires the combination of skilled visual effects artistry and technical know-how. And, as Image Engine’s Daniel Elophe suggests, faith from the filmmakers. “It was a ballsy move for the executives to go, ‘We’re going to create a digital actor of a recognizable person who’s going to stand right next to the other one and they’re going to be front and center and close to the camera. And it’s going to work.’”