‘3 Body Problem’ VFX Supervisor Stefen Fangmeier On Balancing Interplanetary Realities In Netflix’s Ambitious New Sci-Fi Series

The premise of 3 Body Problem – the first in a trilogy of novels by Liu Cixin, appearing March 21 as a Netflix streaming series – was simple. What happens when three suns orbit a planet? The suns’ alternating proximities cause gravitational effects and climate fluctuations that throw civilizations into chaos and lead inhabitants to seek an escape from their doomed world. Those Trisolarians contact a scientist on Earth, in Revolutionary China, and decades later use multidimensional physics to prepare for planetary migration.

To adapt the science fiction saga, showrunners David Benioff, D.B. Weiss, and Alexander Woo shaped elements into an eight-part thriller focused around a group of international physicists in London who uncover the impending invasion. The narrative involved the secret service (Benedict Wong, Liam Cunningham), rogue operatives (Rosalind Chao, Jonathan Pryce), and a cadre of young scientists (among them Eiza González, Jovan Adepo, John Bradley, and Alex Sharp).

The production reunited many of Benioff and Weiss’ Game of Thrones team. These included visual effects producer Steve Kullback and visual effects supervisor Stefen Fangmeier, who joined with special effects and prosthetic effects artists at Shepperton Studios in the U.K. and eight international visual effects studios to create a heady brew of imagery.

Central to the series are visualizations of the ‘three body problem’ depicting alien sun interactions in a hyper-real virtual game. “There was not only the challenge of creating the realism of the game,” notes Stefen Fangmeier, “but also a bigger challenge in terms of filming these scenes. People have been creating environments cg for decades now, and the first environment we see was not complex – it was a barren landscape with a temple. But because the lighting changed, with three suns rising and falling, the question was, how do we shoot this?”

In game level one, scientist Jin Cheng (Jess Hong) meets a robed Count and his young Follower (Eve Ridley) as lighting swims around them. Production designer Deborah Riley and cinematographer Jonathan Freedman staged the scene in an LED shooting environment at Shepperton.

“We used LED panels that were programmable with light sources that could move,” Fangmeier explains. “That made for more complex shooting scenarios in terms of lighting changes. Normally, shooting exteriors on stage is tricky because stage lighting doesn’t ever quite look like the sun. But we got away with that in this environment because it was a simulation. The landscape was simplistic in the sense that there was not much complexity to it, but it had to look absolutely real to make the game impressive to the players. The lighting technician programmed animation for lighting changes going from daylight to dusk to night very quickly.”

As the suns scorch the landscape, The Follower seemingly submits to searing heat that shrivels her body. Prosthetics designer Tristan Versluis fabricated a flattened carcass capable of being rolled like parchment for later rejuvenation in a ‘dehydratory’ rebirth. Scanline VFX created dehydration and later rehydration effects via complex 3d animation.

“The process of the girl becoming this [husk], with water oozing out, revealing bones and contortions, was supposed to be a voluntary process,” says Fangmeier. “It was something that the Follower willed herself to do, and it was an illustration for Jin to show how the Trisolarians preserved themselves when their planet became uninhabitable. All the vr sequences were meant to educate the humans that play as characters in the game.”

Jin and her friend Jack (John Bradley) enter level two in a middle ages cathedral, which succumbs to terrifying incineration. The production initiated cathedral interiors in Wells Cathedral in Somerset, England. Cinematographer P.J. Dillon placed light sources outside cathedral doors and windows to simulate blazing alien sunlight. Scanline VFX then animated stained glass windows melting and pyrotechnic effects, including the Follower on a horse nightmarishly engulfed in flames.

“We shot a real horse from a mobile camera vehicle,” notes Fangmeier. “We had that for reference, but the horse and Follower ended up entirely animated in cg. Because of this precious location, we didn’t use practical fire [other than] candles on their stands. However, warm, interactive lighting was used to give a sense that the characters on the altar set piece were illuminated by all the cg fire that Scanline added later.”

In the aftermath, an enigmatic figure (Sea Shimooka) appears in a volcanic landscape. “We used a lighting strip on the floor for interactive light as she walked across the lava. That’s generally the rule: when you are not in a real location, you build what actors interact with. The rest is computer generated.”

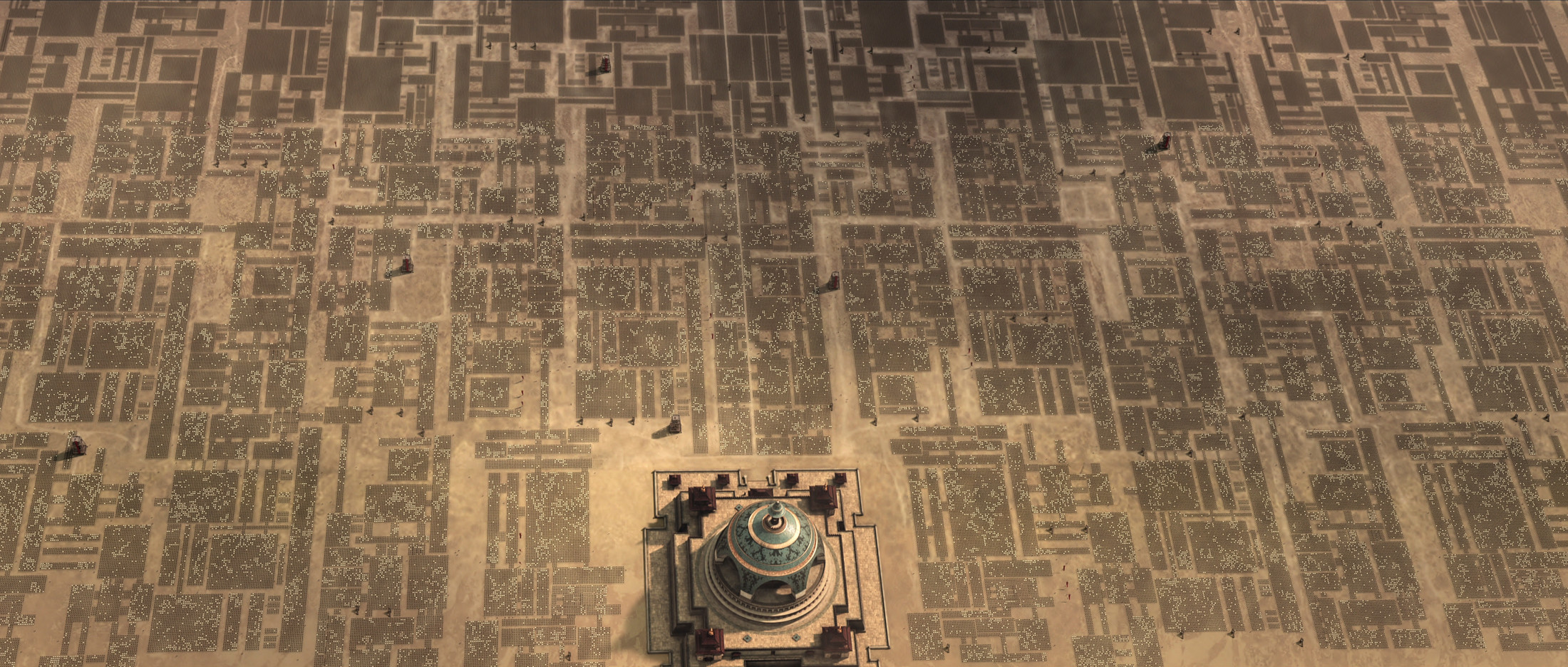

In level three, Jin and Jack visit a recreation of the Persian temple of Omar Khayyam (Jason Forbes) surrounded by 30 million Mongolian soldiers. Only 40 performers in costume represented soldiers on set. Scanline VFX created the entire environment.

“The army went to the horizon with mountains in back,” says Fangmeier. “Scanline used crowd simulations that took pawns and duplicated their position – that was done a lot in Game of Thrones. On this, I don’t know if we actually had 30 million soldiers, but it certainly had scale. For the changing lighting on actors, P.J. Dillon used animation in the LED panels based on previs that we created in Unreal Engine.”

The production built half of the temple’s upper platform and a portion of the roof, and stunts and special effects suspended cast members on wires as gravity fails.

“Some of the soldiers flying by were also shot as elements,” adds Fangmeier. “I had requested that they wear helmets that covered most of their faces, which made using digital versions of them easier. I also requested they wear gloves because digital hands, to me, easily stand out as fake. For standing soldiers close to camera, we tried to favor real performers, but we often had a digital [character] right next to a real one, so they had to match perfectly.”

Scenes leading in and out of the game featured characters donning a sleek, chromium headset. Screen Scene VFX in Ireland addressed the conundrum of how to stage headset scenes without revealing filmmakers mirrored in the prop.

“The prop reflected everything,” notes Fangmeier. “They had to replace whatever was visible in the room – the camera operator, camera gear, lighting flags. Additional vfx supervisor Rainer Gambos captured photogrammetry of each set, and gave that to Screen Scene so they could clean up and replace the reflections.”

The helmet’s chrome interior then liquifies and transports the viewer into virtual reality. “We used an extreme closeup of each actor’s eyes, projected that into the helmet interior, and Scanline came up with a neat visual, swirling and then suddenly entering the game environment. BUF also did some of those game sequences, one in episode two and the last one in episode five, which was the most scientifically complex.”

Scientists exposed to Trisolarian influence are plagued with visual hallucinations of jagged, illuminated numerals counting down to zero. BUF generated the unnerving visions. “We did hundreds of versions to get to that design,” Fangmeier relates. “Nobody wanted it to look like a digital clock, but the numbers had to be legible, and it needed to look agonizing. We imagined proton-sized ‘Sophons’ flying about at near lightspeed while etching these numbers into the retina.”

Sophons were conceived as a proton-sized supercomputer that first affects terrestrial particle accelerators and then, later, manifest in the sky as a warning to Earth’s citizens worldwide. BUF handled Sophon imagery.

“BUF did all of our unusual stuff because that’s their forte,” says Fangmeier. “It was quite something to figure out those concepts, especially with the proton unfolding from ten dimensions to two. That took a while, and sometimes I’d think, ‘We’re never going to get this!’ We’d show new versions to our showrunners, and the reaction was, ‘Yeah, it’s not quite what we want.’ Those were the creative challenges.”

While the series featured diverse tasks – from photorealistic animal animation at Image Engine Vancouver, international period settings, scientific hardware, and a show-stopping destruction sequence in Episode Five that visual effects supervisor Boris Schmidt and his team oversaw at Scanline – Steve Kullback planned resources strategically.

“This was our first season, so we had a generous amount of time, especially in postproduction,” recalls Fangmeier. “I was on the project for two and a half years. That is not typical for a series, and that was very helpful with creative iterations. Season two – if it happens – will venture 200 years into the future, so I don’t know how the schedule for that will go. We’ll have to wait and see.”