‘Mouse in Transition’: When Everyone Left Disney (Chapter 7)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition will be published every Friday on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Read Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Read Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Read Chapter 3: The Disney Animation Story Crew

Read Chapter 4: And Then There Was…Ken!

Read Chapter 5: The Marathon Meetings of Woolie Reitherman

Read Chapter 6: Detour into Disney History

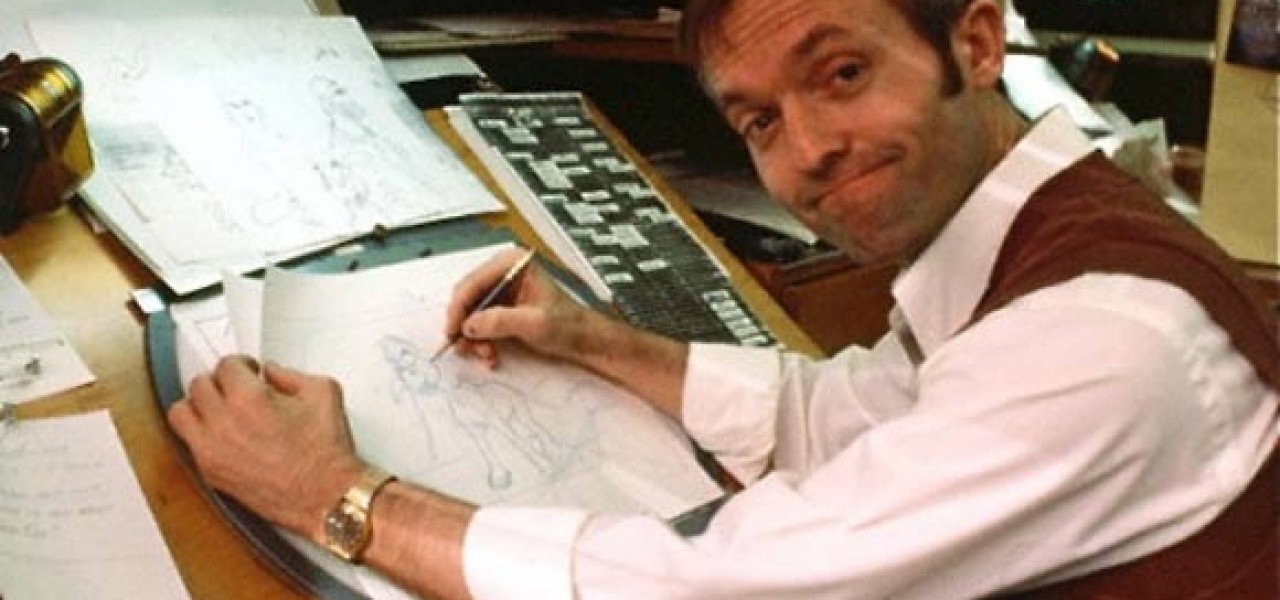

Don Bluth smiled at me.

“I wouldn’t worry about being laid off from Disney’s, Steve. Nobody gets laid off around here. When somebody messes up, the studio just sends them to WED.”

(WED, if you don’t know, was a Disney subsidiary in nearby Glendale that developed rides and attractions for Disneyland and Disney World. Its name was an acronym for Walter Elias Disney, and a number of feature animation employees had migrated there over the years.)

“Ah,” I said, just to be saying something. (“Ah” sounded more intelligent than “Huh?”)

We were off to one side of the Disney commissary where a wrap party for the animated featurette The Small One was in full swing. Don had directed the picture after finishing work on Pete’s Dragon. And a rift had developed inside the department during its making.

Mr. Bluth had taken over direction from Eric Larson, a well-loved veteran and one of Walt Disney’s iconic “Nine Old Men.” Eric mentored many of the newcomers in the department, and some of the younger employees were less than thrilled about the change. Some staff members felt that Eric had been pushed out of the director’s chair, and there was a general suspicion that Don was favoring animators who had worked on his outside project Banjo, the Woodpile Cat by assigning them the best scenes from The Small One. This, naturally enough, caused more resentment to bubble up. Gag drawings that depicted Bluth-allied staff (labelled “Bluthies”) in unflattering ways started cropping up in various wings of the animation building. Don was not happy about the wall humor.

At the wrap party—populated by Disney administrators, animation employees, and CEO Ron Miller with his wife Diane Disney Miller—Don seemed detached and a touch sardonic. I chalked it up to the recent department disputes and grumblings.

I was wrong.

Don was on the brink of walking away from the studio and taking a sizable number of Disney animators with him, all of them off to make their own feature The Secret of NIMH. But all this was unknown the night of The Small One celebration. The scuttlebutt around the lot was that Don had told Mr. Miller that he would stick around until the completion of The Fox and the Hound, so all was food, drink and merriment.

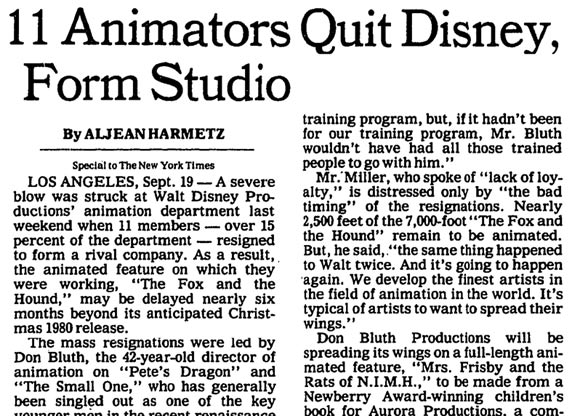

But weeks later the roof caved in. Don submitted his resignation on a Thursday. A large part of the animation staff did likewise on Friday.

Management freaked. Ron Miller asked Don Duckwall what the hell was going on, and Don confessed that he didn’t know. Soon thereafter, Duckwall and Ed Hansen (Duckwall’s administrative second-in-command) started asking staffers if they were staying, and offering animators who were still in the fold battlefield promotions. (An up-and-coming animator named Linda Miller was called in and offered a jump to directing animator; she told Duckwall and Hansen—much to their shock and surprise—that she was leaving with Mr. Bluth.)

The mass resignations turned the Disney animation department upside down. The first bit of smoldering fallout was that the release date for The Fox and the Hound got pushed back. The studio didn’t have the talent to get it out on schedule, and Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston—who had by this time retired to write a coffeetable book entitled The Illusion of Life—had minimal interest in UNretiring.

The second piece of fallout was that Don Duckwall, after decades at the studio, was asked to retire. (Apparently when there’s a surprise exodus of key personnel, and the chief executive is ticked off, there has to be a fall guy. And in this case, Mr. Duckwall was the designated sacrificial lamb.)

But Don and his troops were not the only departures just then. Months before, Larry Clemmons had acceded to his wife Cassie’s suggestions to retire, and gave notice that he was leaving after a twenty-three year run of steady employment. (Thirty-three total years at Disney, if you count his Hyperion studio days.)

I knew Larry had mixed feelings about going. He loved the meetings, the recording sessions, and the general camaraderie. He loved the rhythms of the studio workdays. He loved the long lunches with old friends in the commissary’s executive dining room.

But all things, both good and bad, come to an end, and Larry slowly packed up his office. And on his second-to-last day of Disney employment, he took me to a French restaurant next to Universal Studios.

And at that last dinner, he reminisced about Bing Crosby’s chintzy Christmas presents:

“Bing always handed out flimsy little wallets to staff, wallets with his logo on it. But he had a sense of humor about the cheapness of the things. When one of the writers waved the wallet at him and yelled ‘Hey Bing! I got your form letter!’ Crosby fell on the floor laughing.”

…and Walt Disney’s occasional prickliness:

“When I was writing monologues for Walt on the Disneyland shows, there was another guy who did one of the intros and used the word “modicum.” And I read it and said, ‘Walt? I don’t think you’d say the word ‘modicum.’ Walt glared at me, raised one of his eyebrows and snapped: ‘Whattaya MEAN? I use the word modicum all the time! Modicum. Modicum! MODICUM!’ …”

…and, also, the antics of Larry’s close friend Ward Kimball. Larry recounted how Ward stuck a hand-lettered sign on the back of Leopold Stokowski’s fancy convertible reading “Stokie and his hepcats.” It was a long, enjoyable dinner.

A couple of days later, Larry drove away from the studio for the last time. He was a bit sad about it, but he knew it was time to depart. Within a week he was in Friday Harbor, Washington, in the middle of the Puget Sound. There he remained in contented retirement until the big studio mogul in the sky called him to his next job.

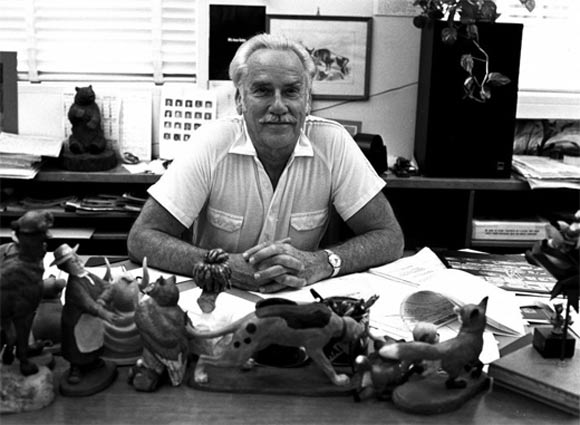

Wolfgang Reitherman was among the last of the Hyperion Studio brigade to exit Disney Feature Animation. Studio management had asked him to step back from command and let junior personnel take the reins, but Woolie had a tough time doing that. Finally, Art Stevens, the second director on The Fox and the Hound, forced the issue with upper management, demanding that Mr. Reitherman stop second-guessing his decisions. Woolie was told that Mr. Stevens would now be a co-equal, and take over day-to-day responsibilities on the picture.

Woolie, however, wasn’t through offering his creative input. He knew that the middle of the feature sagged story-wise, and came up with a solution: insert a musical number featuring a sexy female crane, voiced by the Latin entertainer Charro. Woolie supervised the creation of sequence boards, got a scratch song recorded, then oversaw the filming of live-action reference featuring Charro in a pink leotard.

Art Stevens was horrified. “We can’t let that sequence in the movie! It’s totally out of place!” he complained to management. After reviews and conferences, Reitherman’s crane sequence was put on ice. Art was right about Woolie’s musical comedy interlude being a round peg in a triangular hole, but Woolie was correct that the middle of the picture needed punching up.

After the crane sequence went into limbo, Woolie worked on a couple of development projects that went no further than the treatment and story sketch phase. The studio gave him some consulting work, but he seldom consulted. By the early 1980s, he was gone.

I saw Wolfgang twice after he cleared out his office: once at lunch at a tony, quiet restaurant four blocks from the studio, and again at a banquet honoring animation veterans. He was in high spirits that night, and I like to think his retirement years had been enjoyable for him.

But Woolie was a workhorse, and would have been delighted, I think, to have spent the years after The Fox and the Hound on one last feature, one final short. Unfortunately most human beings don’t get everything their hearts desire, and I suspect that Woolie didn’t get his.

Among the old-timers I knew, only Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston went out the way they wanted. Both of them finished their animation on The Fox and the Hound on the first floor, then moved up to a spacious office on the third floor to write The Illusion of Life, which turned out to be a best-selling classic.

Some lucky few get to exit EXACTLY on their own terms.