‘Mouse in Transition’: The Trials of ‘Oliver & Company’ (Chapter 17)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition are published on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Chapter 3: The Disney Animation Story Crew

Chapter 4: And Then There Was…Ken!

Chapter 5: The Marathon Meetings of Woolie Reitherman

Chapter 6: Detour into Disney History

Chapter 7: When Everyone Left Disney

Chapter 8: Mickey Rooney, Pearl Bailey and Kurt Russell

Chapter 9: The CalArts Brigade Arrives

Chapter 10: Cauldron of Confusion

Chapter 11: Rodent Detectives and Studio Strikes

Chapter 12: Disney Dead-Ends & Lucrative Mexican Caterpillars

Chapter 13: Basil Kicks Into High Gear

Chapter 14: “Call Us Mike and Frank”

Chapter 15: The Arrival of Jeffrey Katzenberg

Chapter 16: A Gong Show with Eisner and Katzenberg

My work on adapting Rudyard Kipling’s “The Man Who Would Be King” unraveled swiftly. I banged out a treatment, submitted it to Jeffrey Katzenberg, and he decided my take on the story wasn’t what he was looking for. (A dozen years later, he made the tale at DreamWorks Animation under the title The Road to El Dorado. Maybe I should have written more drafts, or gotten writer Pete Young’s suggestions, or generally kept pushing. But I wasn’t that smart.)

Most of the animation department had moved to its new, dingy digs in Glendale. Burny Mattinson and the Basil of Baker Street crew had already taken up tenancy, and the Basil animators were settling into their new offices and cubicles. Pete Young was still housed in the Burbank studio, and I found myself shuttling back and forth between story artists working on Oliver Twist and artists and directors still doing Basil of Baker Street.

Which led, by and by, to a rupture with Pete. Driving back and forth between meetings, buildings, and desks, I started feeling over-worked and under-appreciated. The greater reality was that little Steve was full of himself, and didn’t appreciate the pressure Pete was under, heading up a new picture under a new studio regime.

One afternoon at the start of an Oliver story session, Pete told me to take notes, and I tartly responded: “I’m not a freaking secretary.” A chill snaked through the room. Pete glared at me and said, “Whatever you want.”

At that moment, under the fresh tensions of a new studio regime and stiff new creative demands, our long friendship splintered into small pieces, only I was too thick to know it. But I figured the new dynamic out soon enough. Over the days and weeks that followed, Pete became cool, distant, and less communicative. Our long lunchtime walks came to an end.

That summer of 1985, as Disney animation staff departed the building it had occupied for 46 years, there was another historic marker: Woolie Reitherman, retired five years, was killed in a car crash three miles from the studio. The last time I’d seen Woolie he had been laughing it up at an Animation Guild banquet that honored old-timers. He had been jovial and energetic that night, dancing with his wife and hoisting a few adult beverages. I was lucky enough to get myself seated at his table, and noted that he was a little grayer but just as vibrant as ever.

And now he was dead.

Most of the animation department showed up at a church on Olive Avenue to bid him farewell. Some of the animators, assistants, and board artists had worked closely with him, others not. I sat in a pew in the middle of the sanctuary, musing how quickly life flashes by: one minute you’re in a story meeting spit-balling ideas with the boss, then you’re hunched down under a stained-glass window, remembering it all at the boss’s funeral.

The Oliver story crew was among the last groups to pack up and move to Glendale. Early one morning I departed my cramped space on the main lot and became the occupant of a windowless office jammed between Pete Young and new animation staffer Tim Disney (Roy E. Disney’s oldest son.) Pete now spent the bulk of his time with a soft-spoken animator named George Scribner, who was being groomed for a director slot on Oliver. He and Pete spent mornings and afternoons cobbling outline boards together for the new feature; I was in and out of Pete’s office spit-balling ideas and offering dialogue suggestions. But a coating of frost remained on our relationship.

Roy Disney was the new head of the animation division. He wasn’t in the Flower Street building every day, but when he came in he made a point to review Pete’s work and give input. Pete was a good soldier and incorporated Roy’s suggestions into the boards, even ones he didn’t wholeheartedly embrace.

Weeks later an official announcement for the production supervisors of Oliver came down: George Scribner and Richard Rich (one of The Black Cauldron directors) were the helmers for the picture, and Pete Young was story director.

The relaxed atmosphere of the “old” Disney whipped away like leaves in a stiff autumn wind. The pace of work picked up, and Pete was under more stress than ever. I had the feeling he wasn’t thrilled with some of Roy’s input, though he didn’t admit it in so many words. But his tight mouth and blank stares into space were giveaways.

In another part of the building, Tad Stones was developing a featurette starring Goofy; Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg came to Glendale one day to look at the boards and proclaimed them “great,” but three days later put the featurette on hold. That prompted director Ron Clements to observe to me in a hallway, “You know, these new guys are interesting. When they see something and say, ‘This is the most FABULOUS thing we’ve ever seen!,’ that means ‘Maybe this is sort of okay, and maybe we’ll put it in production.'”

Without warning staff writer Tony Marino was laid off. Tony had been at the studio for years, and I’d always considered him a barometer for the health of my own Disney career. If Mr. Marino was still on the payroll, my job was secure. But if not? I could feel my stomach knot up as soon as I got the news. Peter came out of his dark mood long enough to chide me, “You better watch your step, Hulett. Tony was the canary in the coal mine. And Tony’s now lying on the bottom of his cage.”

Work on Oliver continued on. Roy came up with an idea that Fagin and his gang of thieving dogs would steal a valuable panda from the city zoo. I thought the idea was lame; Pete was miffed that I wasn’t enthusiastic about it. But I wasn’t the story director, and had a hard time faking support.

The main lot communicated that Mr. Katzenberg and Mr. Eisner wanted to see the Oliver story-beat boards, front to back, on the following Saturday. Later on, Jeffrey Katzenberg would perform this task solo, but in those early days Jeffrey and Michael Eisner used a team approach.

Pete worked feverishly to get the boards in shape. He worked late. He worked through lunch. He worked, tense and exhausted, all through the last weekend. And when the appointed Saturday rolled around, Pete was in the building alone to pitch the beat boards, complete with all of Roy Disney’s story suggestions.

Only Roy wasn’t there, and Michael and Jeffrey made no bones about hating the boards. They hated the panda, they hated a lot of the story progression, they hated almost everything that wasn’t Charles Dickens. When I came in Monday morning, Pete told me about the disaster: “Jeffrey and Michael ripped the boards to shreds. The panda they didn’t get at all. There wasn’t one big story point they got behind. So…we’re screwed.”

I told him we could fix it. He shrugged his shoulders, face drawn. His eyes looked like two dark holes punched in a snowbank.

“Maybe. But who knows?” he shrugged again. “Just when you think you have job security, you find out you don’t.”

I knew what was going through his brain because the same things were going through mine: When you do everything you’re asked to do and still get the shaft, what’s left? Nothing but the powdery ashes from the weeks and months of story work.

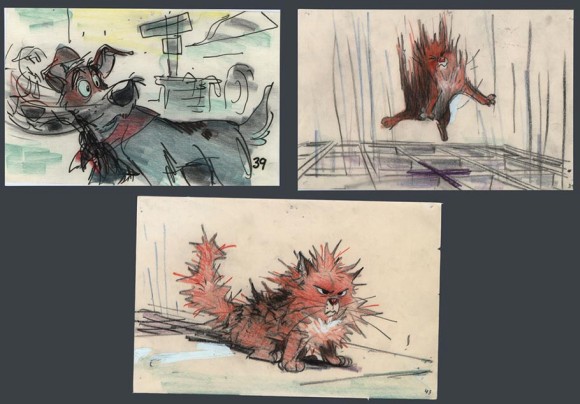

So we started to reconstruct the boards without a panda, without the zoo sub-plot. Pete came up with two new characters, a pair of fierce-looking Dobermans that were Fagin’s enforcers, and story development staggered forward.

But Pete’s heart was no longer in it. He was funny and sardonic like always, but he was also distant. When I threw an idea out in an impromptu office story meeting, Pete would tilt his head, shrug, and say, “Sure, why not? That’s as good to put in as anything.”

Meanwhile, Basil of Baker Street was rolling into its last lap. Most of the sequences had been tied down and a lot of animation had been completed. Burny Mattinson held a screening of the picture for the story crew and directors to see if anybody had any late tweaks or suggestions. Roy was in attendance, and when the lights came up, he looked at all of us and said, “Lots of good stuff here, but you need to switch sequence one with sequence two.”

Burny looked at him blankly. “Switch sequences?”

“Reverse one and two,” Roy explained. “Get to the action faster. It’ll work fine.”

People nodded, looking a bit dazed. Burny grunted. And Roy walked out. There was a long stretch of silence. Finally Burny said, “What is Roy thinking? We can’t change the story order. The story won’t make any SENSE.”

Everyone agreed that swapping sequences made the movie incoherent. The solution? Burny and the directors didn’t change anything. And Roy never brought up the subject again.

A little while later, I found out that Burny had another issue. He and I were sitting around after a board presentation and he groused, “I’ve worked hard to keep Basil’s budget under control, and I just discovered that $500,000 got shifted off Oliver on to us.”

“Us” in this case was Basil of Baker Street.

“Magic studio accounting,” I said.

“Yeah, but it’s still irritating.”

My work on the mouse Sherlock Holmes feature ended, and I focused on Oliver. Pete stayed remote, going though the motions, his energy half what it usually was. But maybe I was projecting. I was subdued and tense myself. The other staff writer had been cut loose, so I was likely the next scribe to get the axe. Three nights out of five I went home sour and irritable.

In early October, Mrs. Hulett and I left on a two-week vacation to the East coast, and my gloom lifted. I didn’t think about Disney Feature Animation, or dream about Disney Feature Animation. It was as if a large rock had been surgically removed from my intestinal tract. This lightness of being lasted all the way through New England’s fall colors, six days at Disney World, and all the way back home.

But the buoyancy vanished with a single phone call. On the first afternoon I was back (a Sunday), Woolie Reitherman’s long-time secretary Larraine Davis called to ask me “if I had heard the news.”

“What news is that?” I asked.

Long pause, then: “Pete Young died last week. The funeral was Friday.” [Note: He was 37 years old.]

I was staring at the living room wall. My hands and arms went clammy. The wall seemed to telescope away from me.

“What?”

“He went home with the flu. A week and a half ago. His throat closed up when he was in bed, and he suffocated. His wife came home from dropping their three girls at school and found him on the floor.”

I stood there holding the phone like it was a block of wood. Trying to wrap my head around what she had said. And failing. I mumbled some thick-tongued inanity, thanked her for letting me know what happened to Pete, and hung up…

I broke the news to my wife, then stumbled out the front door, walking aimlessly through the neighborhood, nine years of memories ricocheting through my head: “You can’t tell them anything until they’re ready to hear it”…”Ken Anderson tried to get you fired”…”Just when you think you have job security, you find out you don’t.”

For the rest of the day, I was disoriented and jittery, feeling like a caffeine freak who’d been hit in the forehead with a nine iron. That night, sleep was intermittent. When I finally jerked awake into the morning light, it hit me with fresh intensity: Pete was gone and life had irrevocably changed.

Within weeks, I found out Pete Young’s death was only the beginning of a new road…

Mouse in Transition has been released in paperback and e-book formats from Theme Park Press. In addition to Hulett’s on-going narrative, the book contains a foreword by Disney director John Musker, a half-dozen interviews with Disney old-timers, and biographical sketches of Disney animation staffers who worked at the studio in the 1970s and ’80s.