‘Mouse in Transition’: The Marathon Meetings of Wolfgang Reitherman (Chapter 5)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition will be published every Friday on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Read Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Read Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Read Chapter 3: The Disney Animation Story Crew

Read Chapter 4: And Then There Was…Ken!

My wrestling match with Ken Anderson now over, I returned once more to Wolfgang “Woolie” Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, working on the story end of The Fox and the Hound.

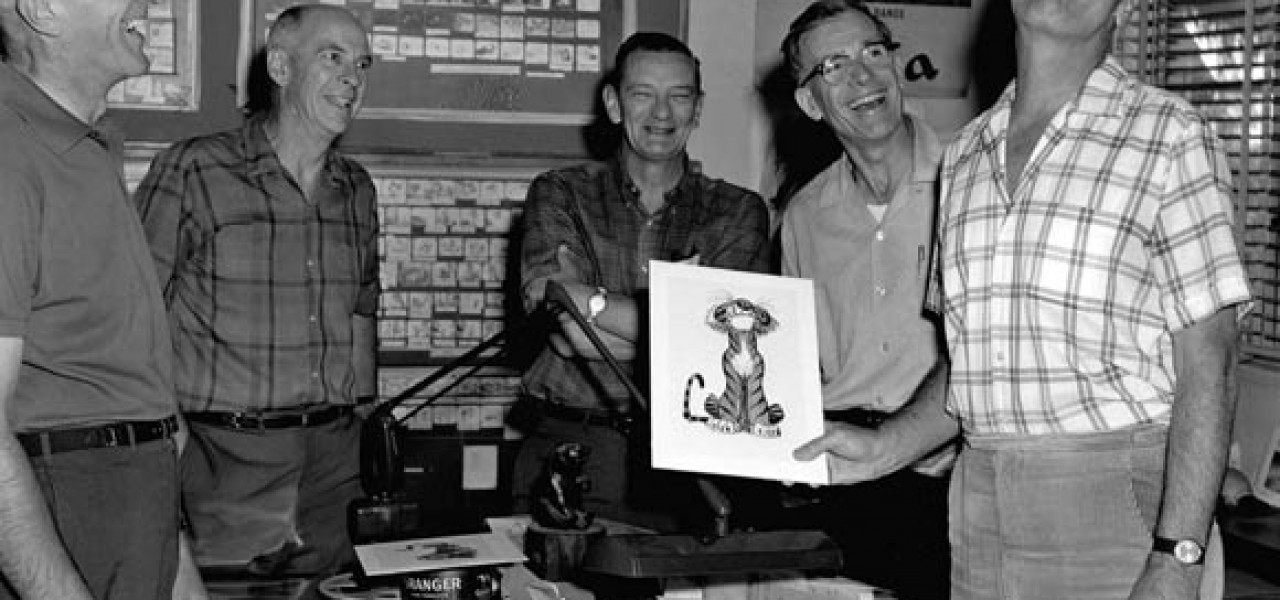

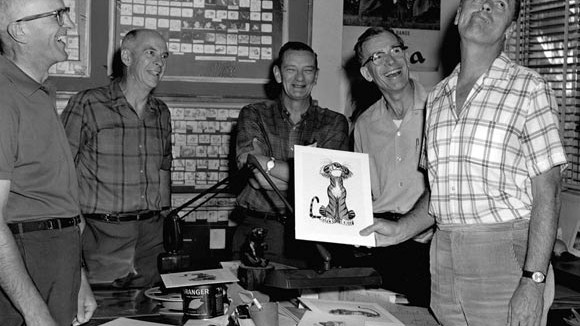

During my time away, development on the picture had picked up, with Larry writing feverishly, and Woolie holding long story meetings in his office with a rotating cast of animators and story persons. And when I say long, I mean like six, or seven or eight hours at a stretch.

Larry Clemmons, Mel Shaw, me, Earl Kress, Frank Thomas, and Ollie Johnston would sit around Woolie’s giant director’s desk and dissect the new script for Sequence Three, dice it into bite-size pieces and then reassemble it. Sometimes this would be for the better, but oftentimes not. I would take notes, and the back-and-forth would go like this:

Woolie: This scene on page two? I’m not sure we should have Big Mama fly into the tree here. Why not if she flies to the top of the hunter’s barn? And the two crows get messed up with the weather vane.

Larry: They’re at the barn in Sequence Five, Woolie. I don’t think it works to have them there in three.

Woolie: Okay, so we have them someplace else in Five. I was never keen on the barn in Five anyway.

Frank: The crows are a problem, Woolie. Ron [Miller, head of the studio] complained to me about them last week. Said they’re still getting complaints about the crows in Dumbo.

Woolie: Larry? You’ll be changing the damn crows, right? To robins or sparrows or some other damn bird?

Larry: Whatever you want, Woolie.

Woolie: Well they gotta be changed. But right now I want Big Mama out of the damned tree. And I want the crows in sooner.

Mel: She’s talking to the fox. Crows come in earlier, they break up the conversation.

Woolie: Maybe the conversation needs to be broken up. We just have a lot of exposition here. It’s boring.

Larry: It’s needed, Woolie.

Woolie: I’ve got an idea. This isn’t any good, but what if …

Mel: If it isn’t any good, why are you telling us? …

And so on.

Story meetings generally went on like this for an hour, then another hour. Woolie would throw out new plot ideas and dialogue, often prefaced by, “This isn’t any good, but …” Larry would yell, “I think I’ve got it!” and recite whatever “it” was. (This type of work environment is old hat for sitcom writers, but it wasn’t always the usual thing for animators and story people on feature animation.)

We would break for lunch, then continue into the afternoon and early evening, trying out new situations and inventing new dialogue. At some point, Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas would have their fill, bail out of the proceedings, and go back down to the first floor to animate. (Ollie used to complain: “I just can’t take those long meetings! I’m not getting any animating done!”) Larry, Mel and the rest of us would plod on, kneading the script like so much warm dough.

When five o’clock rolled around, Wolfgang Reitherman was still as fresh as a budding tulip, and everyone else was exhausted. We would wearily hoist out of our chairs and drag off down the hall, Larry grumbling that he used to write a half-hour script for Bing Crosby every damn week, but writing for damn cartoons went on forever.

The crows got changed to a woodpecker and a sparrow. And Ron Miller was much happier.

But story meetings weren’t the only marathons over which Mr. Reitherman presided. There were also Woolie’s dialogue-picking sessions, where Woolie would have eight or twelve people in his office voting on which recorded line readings they liked best. These meeting would proceed as follows:

Woolie: Okay, let’s hear take number three again. …

[Dialogue]: Hey, what’re you doing, Boomer? The worm’s over here! He’s over HERE!!

Woolie: So … who likes that take?

(Two hands go up.)

Woolie: Jeff? [Jeff is the assistant director.] Play us take number eight.

(Jeff play Take Number Eight. Which sounds remarkably similar to Take Number Three.)

Woolie: How many like that one?

(One hand goes up.)

Woolie: The first part doesn’t grab me, but I kind of like the last sentence. Especially the last half of the last sentence. Jeff?

(Jeff plays Take Number Eight again.)

Woolie: Okay, so maybe we hook up the first half of take number three to the last half of take number eight. Who’s for that?”

(Four hands go up.)

And so on, over and over. As time passes, my concentration starts to fade (like I’m falling asleep.)

When I first heard about Woolie Reitherman’s line-picking sessions, I desperately wanted to attend them. Only veteran story people and animators were invited. It sounded important to me, and I wanted to be involved in whatever was important.

Vance Gerry laughed at me. “You don’t want to go to those meetings, Steve, you really don’t. They’re endless, and the dialogue all sounds the same after awhile. It should be up to the director and animators to pick the takes, not everybody else.”

But I ignored Vance. I was hot to get into this new club, and nothing could dissuade me. And finally I managed to wrangle an invitation. It was a kick to sit with the Big Boys, to have a hand in choosing the dialogue that would come out of the big silver screen at the neighborhood AMC.

At first.

But then I got invited to more dialogue-picking sessions, and then more. And it became less of a kick. In fact, it became a tedious chore. Deciding whether the 23rd line reading of, “Hey, it’s a great day, innit?” was superior to the 19th line reading, when both lines were almost sonically identical, caused a dull ache in the middle of the forehead.

It was then that the wisdom of Vance Gerry’s remark came back to me. “The dialogue all sounds the same after awhile …”

And the day came when I didn’t care if I went to another line-picking session or not. That was followed by a mild dread of getting a phone call to attend another session. And then one afternoon I knew I had changed my outlook because I found myself in Vance Gerry’s room complaining about the damn line-picking sessions, how I wanted to get out of them, and what a waste of time they were.

Vance looked at me, and grinned. “You think?”