‘Mouse in Transition’: The Disney Animation Story Crew (Chapter 3)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition will be published every Wednesday on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Read Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Read Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Larry Clemmons had me writing sequence scripts for The Fox and the Hound, which turned out to be my assignment for the next six months. Part of the package was attending Woolie Reitherman’s marathon story sessions, which often left me drained and dazed. There were also Woolie’s marathon take-selection meetings, which left me drained and bewildered.

Woolie was big on high-attendance, open-ended meetings.

During this time, I had an opportunity to see Robin Hood (Disney’s previous release) and The Rescuers (still waiting in the wings.) The Rescuers was amazingly good, Robin Hood decidedly less so. I wondered how that could be, since both movies had the same creative team. I decided it was one of the ongoing mysteries of the film business. Nobody hit a home run every time at bat.

I also got assigned to look at older features. One day Woolie sent me into a small third-floor screening room to watch Dumbo, and a funny thing happened. As I emerged from the “sweat box” (a term handed down from the un-air-conditioned Thirties) , Frank Thomas came striding down the hall. He gave me a sunny smile and asked what I’d been looking at. I said, Dumbo. It’s sure a nice picture.” Without missing a beat Frank responded, “There’s a mistake in every scene.”

I thought this was a peculiar remark and asked veteran Disney animator Ward Kimball—retired from the studio but whom I often visited—if he knew why Frank might have said it. Ward said, “That’s easy. Frank didn’t work on Dumbo.”

As I wrote sequence scripts for Larry and Woolie, I was also supplying gags, ideas, and bits of dialogue to the half dozen Fox and Hound board artists, busily working to pull the picture into a coherent whole. (Another young writer—Earl Kress—was doing the same down the hall. Earl had broken into animation at DePatie-Freleng, and had worked at Disney for a year. He would go on to win an Emmy for his work on Warner Bros. Animation’s Pinky and the Brain.)

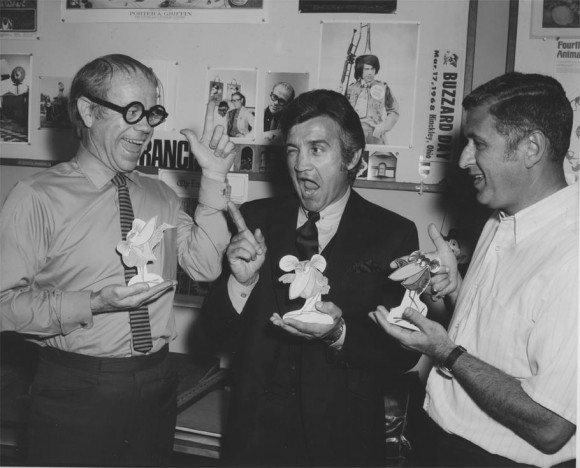

The Disney board artists were a breed unto themselves. There was Ted Berman, one of Wolfgang’s “old reliables.” Ted had been at the studio since 1940, starting as an in-betweener and working his way up the ladder story sketch by story sketch. Mr. Berman had a sign tacked to one of his big cork boards that was telling: “The stuff was funny when it left here.”

There was Vance Gerry, one of the best story minds in the studio. He created drawings that communicated with clear composition, inspired design, and often a small dab of color to emphasize a story point. Vance had come up with some of the best visual ideas for The Rescuers, but nobody would ever find those things out by talking to him, because he raised self-effacement to a high art. He constantly denied that he had much talent or skill. And when Friday rolled around, his catch-phrase was: “Well, fooled them another week.”

Another of his pet sayings was: “Never draw what you can blow up and trace on the Lucie [Lucigraph]; never trace what you can Xerox; never Xerox what you can reuse.” Funny, but highly deceptive, because Vance drew like a man touched by an angel who ran a Renaissance art studio. But then, Vance was a master of misdirection.

Dave Michener was another veteran story artist. He had joined the studio in the middle 1950s, around the same time that Vance hired on. Dave was managing a gas station at the time, and Disney paid so little money that he kept the gas station job for the first year he worked at the Mouse House. For a long time Dave worked as animation giant Milt Kahl’s assistant, and Milt considered him the best right-hand man he ever had. By the time I met him, Dave was a pillar of the Disney story department.

Mel Shaw was a designer and master with pastel chalk who was also deeply involved in story work. Mel had been in the animation business as long as any of Disney’s grizzled veterans, but he’d spent much of his time away from Walt Disney Productions. Starting at Harman-Ising as a teenager during the Depression , he had come to Disney to develop Bambi but left afterwards. Forty years on, he had returned to work on The Rescuers and was one of the key idea men on The Fox and the Hound.

Burny Mattinson, once an animator and before that an assistant, had storyboarded parts of The Rescuers and was now at work on his second feature. He had a light, well-developed drawing style that had evolved out of his years as a book illustrator. Burny had started at the studio at nineteen and eventually ended up as a director and producer.

And then there was Pete Young. Pete looked his last name, like a junior in high school, with thick curly hair and an unlined face, but he’d been at Disney’s almost ten years. He had started as a traffic boy and soon moved to the effects department. Self-conscious about his drawing ability, he could in fact put more personality into a few lines on paper than any artist this side of Vance Gerry. Added to which, he had an uncanny knack for coming up with sequences Woolie liked … and projects the studio greenlit for production. He was the story person who taught me:

“You can never sell a director or management on an idea until they’re ready to buy it. You have to have patience.”

On top of all that, Pete generally knew everything worth knowing in the department. What man was chasing what woman (and the reverse.) What animator was in the doghouse with a supervisor. What ideas the executives on the top floor were contemplating. He had a vast network of co-workers who dropped into his large, second-floor office morning and afternoons with the latest news regarding upper management and the latest internal department battle.

He and I would become close chums in the years ahead.

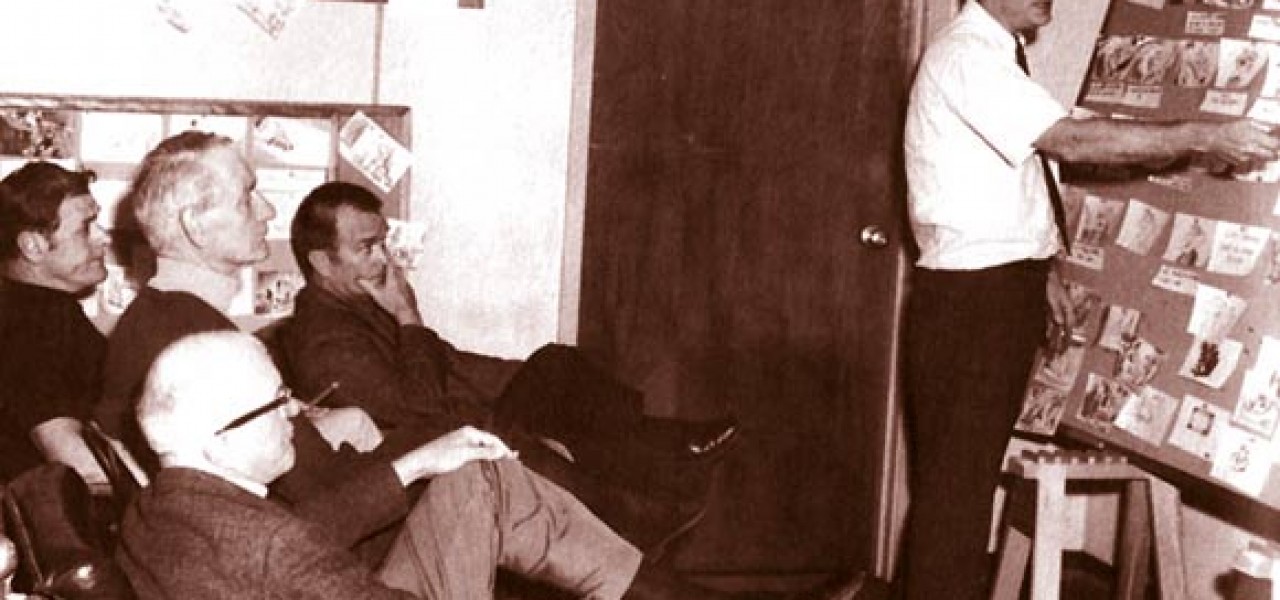

A Wolfgang Reitherman storyboard meeting on The Fox and the Hound almost always started abruptly and without prior notice.

This is the scene: I’m sitting at the corner of a big assistant director’s desk, scribbling ideas on a pad. Dave Michener is pinning a final drawing on a big cork board, one of four that is filled with drawings, top to bottom and fore and aft. Without warning, Woolie materializes in the door way, unlit cigar in the corner of his mouth. “So, what you got going on here?”

Dave’s pinning session comes to a quick end and a pitching session starts. Leather and wood chairs come together in a half circle as if by magic, and a half-dozen artists and writers come out of nowhere to plunk down in them. Woolie’s in the middle, Larry Clemmons next to him sucking on an unfiltered Chesterfield, Vance Gerry leaning forward, Ted Berman leaning back. And me off to one side, pen and notepad in hand.

Dave steps to Board One and presents the sequence: Tod the fox creeps through a forest glade full of steel traps; suddenly Tod sets a trap off, quickly followed by more snapping steel jaws and shot gun blasts. A frantic chase unfolds, ending with the fox trapped in his burrow with soul mate Vixey and their three bewildered pups. The hunter burns brush to smoke the furry animals out, then there is more slashing and shooting as the foxes break out a rear exit. Action action ACTION.

Dave finishes. Woolie rotates the unlit cigar stuck in his mouth. “Hmm. Well, yeah. I’m not sure I buy all the time we’re taking to get to the damn burrow. What do you guys think?”

A grunt from Vance. Larry puffs on his cigarette, finally says, “Maybe we can lose some of the trap drawings. Tighten it up.” Ted Berman allows that it seems to go along pretty good to him. I stay silent and take notes.

Woolie heaves out of his chair and folds over five of Dave’s drawings, pinning the upper left corners of each onto the lower right corner, signifying it’s out of the sequence. Board by board, row by row, he works his way through the dialogue and action. Folding, repinning.

“We really need the kids in here? Slows things down. Maybe just the girl fox. And the hunting dog should be more involved. Have him dig at the entrance. Let’s see more of what’s going on inside the burrow. See more of the foxes’ desperation…”

Woolie is methodical. Woolie is relentless. He scribbles illegible drawings, pins them up, repositions sketches. By the time an hour’s gone by, the boards have a third or half the drawings pinned over. And Dave has a new set of marching orders. Lose the kids. Speed up the action in and around the burrow. Get the lead characters from the traps to the burrow quicker.

Finally we stand up to leave. Woolie heads for the door, looks back at Dave Michener. “How long you need to do the changes?”

Dave shrugs. “A week. Six days.”

Everybody exits. In the hall, Vance sighs and shakes his head. “Six days? And then we’ll have another meeting and Woolie will tear up his boards again? I couldn’t take it, not every six days. I don’t know how Dave does that. Me, I need at least two or three weeks between meetings.”

Dave’s work on Sequence 11 continued for another eleven months. Every week or three, Woolie strolled in unannounced and sat down to hold court again. And eleven months later, after multiple story sessions and thousands of new sketches from Dave, Sequence 11 was within eight drawings of where it had been on this date.