‘Mouse in Transition’: The Arrival of Jeffrey Katzenberg (Chapter 15)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition are published weekly on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Read Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Read Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Read Chapter 3: The Disney Animation Story Crew

Read Chapter 4: And Then There Was…Ken!

Read Chapter 5: The Marathon Meetings of Woolie Reitherman

Read Chapter 6: Detour into Disney History

Read Chapter 7: When Everyone Left Disney

Read Chapter 8: Mickey Rooney, Pearl Bailey and Kurt Russell

Read Chapter 9: The CalArts Brigade Arrives

Read Chapter 10: Cauldron of Confusion

Read Chapter 11: Rodent Detectives and Studio Strikes

Read Chapter 12: Disney Dead-Ends and Lucrative Mexican Caterpillars

Read Chapter 13: Basil Kicks Into High Gear

Read Chapter 14: “Call Us Mike and Frank”

Michael Eisner lounged his six-foot-four frame in a conference room chair. He was wearing jeans and sweatshirt, but why not? It was a Saturday morning. Animation directors and story artists, all in their twenties and thirties, sat at a long table on three sides of him. Mr. Eisner’s big German Shepherd noshed a rawhide strip in a corner of the room.

We had been called to this meeting with the new CEO because he wanted to find out about us, to pick our brains, to chitchat. A dozen of us sat stiffly in chairs, waiting for his questions. None of the questions were tough, things like,”How long have you worked at Disney?” … “What do you do, exactly?” … “Where do you think animation should go?,” but we were uptight just the same. This was the Big Man, fresh from Paramount.

Pete Young was among the first to get quizzed.

“So, what’s your name?”

Pete told him.

“So how long have you been at the studio, Peter?

“Since 1970.”

A startled look. “1970?!,” said Eisner. How old were you when you started here? Fourteen?”

It was an obvious question. Pete looked like he was maybe a year out of college if you didn’t focus on the little highlights of gray in his thick, curly hair. His face was young and unlined. He resembled a choirboy who knew a few secrets.

“Twenty-three.”

Michael Eisner said that was hard to believe, and then went on around the table, asking more questions. When he came to me, I told him I had been at the studio since ’76, and was a semi-nepot. He asked what that meant. I explained that my father, Ralph, had worked at Disney as a background artist from the Hyperion days to the early seventies, but had died before I applied for the job. Therefore, I called myself a semi rather than full-fledged nepot.

Michael Eisner grinned. “Hey, I’ve got kids. I like to think I’ll help them get a job when the time comes.”

The questioning went on. Tad Stones got into a polite debate with Michael about the kind of animated features the company should make. Mr. Eisner didn’t appear to take offense, but I sure as hell wouldn’t have argued with the chief executive of the company, not on the first meeting.

When Eisner had worked his way around the table, he explained his philosophy of movie-making: “You need a solid idea. And then you need to execute that idea well. Fish-out-of-water stories are good, but you need some twist. Beverly Hills Cop was a fish-out-of-water story. We took a street cop from the ghetto and put him in the most different kind of place we could think of. What could be more different than Rodeo Drive and Beverly Hills? You’ve got fancy stores and big mansions. You’ve got the Beverly Hills Police Department. Audiences loved the picture and it made a fortune. The thing was a fresh idea, you know? And it was well executed, with a good script, good cast, a good director. It’s what we’re going to do around here. It’s what we’ll be doing with animation.”

The new CEO had definite ideas about animated features. They had to change from what they had been as far as he was concerned, had to be modern and “with it,” had to tackle new subjects. Nobody except Tad argued with him.

In the first months of his regime, word circulated that Eisner and company wanted to outsource most Disney animation to Korea and Taiwan. Many cartoon staffers figured that they would be looking for other work soon, as the work at Walt Disney Productions would be gone. After awhile I got tired of the rumors, tension, and suspense. Roy Disney had a new office on the third floor of the animation building, and I paid it a visit, hoping to find out what was really going on.

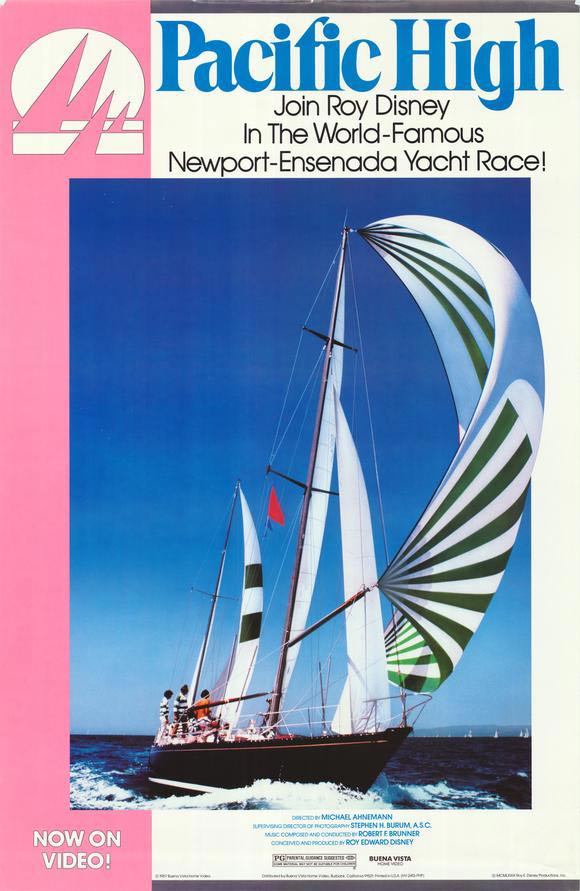

Roy’s office space wasn’t large, but it already had his personal stamp: model ships…wood paneling…framed pictures of sailboats on the walls. And there was a poster for a documentary Roy had made titled Pacific High hanging near the door. The poster’s graphics and layout led me to believe the movie was about a long sea voyage through the South Pacific.

Roy was sitting behind a wooden desk and came out from behind it to greet me. He looked a lot like his Uncle Walt, with the same moustache, same parted hair. He was low-key and self-effacing, but seemed fully aware of his place in the corporate structure. He had engineered the coup against Ron Miller, after all, and knew what his power and leverage were. He was dressed in a sweater and open-necked shirt, and puffed energetically on a cigarette. Also like Walt.

I asked him point-blank if Michael Eisner and Frank Wells were planning to get rid of the animation department. He took a long draw on his cigarette.

“They talked about it,” he said. “They wondered why everything couldn’t be outsourced to Asia. I told them animation was the center of the company. That it needed to KEEP being the center of the company.”

“So then, the department’s staying together?”

“Think so. I told Frank and Michael I wanted to head up animation. They thought that was a doable idea.”

What changes were coming, I asked. Was the department going to grow? Shrink? He answered that he thought they wanted to do more features, maybe one a year.

I couldn’t think of anything more to ask, thanked him for his time, and walked to the door. I pointed at the Pacific High poster and mentioned that William F. Buckley had written a book called Atlantic High, also about sailing. Roy grimaced.

“Buckley, the son of a bitch,” Roy said. “The documentary came out before his damn book. And so one day he calls me up and says, ‘Roy? I’ve got a memoir of a sailing trip coming out and I’m titling it Atlantic High. That’s all right with you, isn’t it?’ It wasn’t, but I say, ‘Whatever you want to do, Bill.’ I didn’t yell at him, but he’s still an S.O.B.”

Don’t mess with sailors.

The story department went on as before, continuing work on Basil of Baker Street. But Disney animation was changing around us. Word circulated that Michael Eisner wanted to open a television animation division, throwing out an idea for its first show: a half-hour series based on the small, chewable candy called Gummi Bears. (Pete and I wondered what the hell THAT was about, but the show turned out to be a popular hit.) A former assistant animator named Michael Webster was appointed head of the new division and started building a staff. Several animation employees, among them Tad Stones and animator Dave Block, soon left to join the new division. Pete Young even tried his hand at drawing a television production board.

And still more change happened, this time in the form of a short, wiry man with thinning hair and big glasses who went by the name of Jeffrey Katzenberg.

Jeffrey had worked for Eisner and Barry Diller at Paramount; nobody knew much about him except that he was tenacious. Mr. Katzenberg turned out to be several clicks past tenacious. He arrived at the studio in early 1985, and commenced plowing through Disney’s various departments like a caffeinated hunting dog. (It wasn’t long before the animation story crews were getting packages from Jeffrey messengered late at night to their homes, instructing everybody to read the contents “for a meeting early Monday morning.” Like I say, caffeinated.)

One Monday Burny Mattinson came to me and said, “Jeffrey wants to see what we’re doing with Basil of Baker Street. You’re going to pitch the story-beat boards to him.”

“The boards hanging out in the hall?” I asked, both palms suddenly sweaty.

Burny nodded. “Two o’clock tomorrow afternoon. He’s pretty busy, but that’s when he can squeeze us in.”

“Is this where he decides if we get to keep doing the movie?”

“Maybe. Probably. So be good.”

I spent most of Tuesday morning looking at the boards and rehearsing, then looking at the boards and rehearsing some more. At two o’clock the Basil story crew stood tensely in the second-floor hallway of 2-D, waiting for Jeffrey’s arrival. At two after two he came striding down the hall, shook hands with everybody, and I launched into my spiel about a detective mouse in London, his arch enemy Ratigan, and the nefarious plot to take over all Mousedom.

Mr. Katzenberg listened with laser-like intensity. I managed to avoid mangling the plot or muddying up the characters. When I got to the end and took a deep breath, Jeffrey said, “This has possibilities. Paramount’s doing a picture called Young Sherlock Holmes. It’s still in work, but it’s good. This story’s in that vein. So we’ll keep going on it.”

With that, he turned on his heel and walked off down the hall. For half a second I felt as though I was having an out-of-body experience, gazing down on the boards, the directors, and story artists, while suspended in a cloud.

“So,” Burny said at last. “We’re still in business.”

“Seems like it,” I said.

There was an audible sigh of relief.

Mouse in Transition has been released in paperback and e-book formats from Theme Park Press. In addition to Hulett’s on-going narrative, the book contains a foreword by Disney director John Musker, a half-dozen interviews with Disney old-timers, and biographical sketches of Disney animation staffers who worked at the studio in the 1970s and ’80s.

.png)