‘Mouse in Transition’: Mickey Rooney, Pearl Bailey and Kurt Russell (Chapter 8)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition will be published every Friday on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Read Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Read Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Read Chapter 3: The Disney Animation Story Crew

Read Chapter 4: And Then There Was…Ken!

Read Chapter 5: The Marathon Meetings of Woolie Reitherman

Read Chapter 6: Detour into Disney History

Read Chapter 7: When Everyone Left Disney

Don Bluth and his troops were gone, but the studio still had to get out The Fox and the Hound. Art Stevens, now lead director, was slowly pulling the picture together with the animators and layout artists who remained loyal to the Mouse. But the animation department was still in flux.

My friend Pete Young, working on Act I of The Fox and the Hound, saw his opportunity to put his, “Don’t give them fresh ideas until they’re ready for them” philosophy into operation. Lo and behold, Pete got new story wrinkles and plot points into the film’s evolving narrative. He had waited for the right moment, and boom boom! BOOM! He sold his new ideas in the course of two story meetings.

Meanwhile, up on the third floor, I was writing new outlines and revising dialogue. Most of the voice actors had been cast: Pearl Bailey as Big Mama, Corey Feldman as the young hound dog Copper, Jack Albertson (of TV’s Chico and the Man) as hunter Amos Slade. There was Jeanette Nolan as the Widow Tweed (a solid second choice after Helen Hayes turned down the part) and Nolan’s husband John McIntire as a cranky badger.

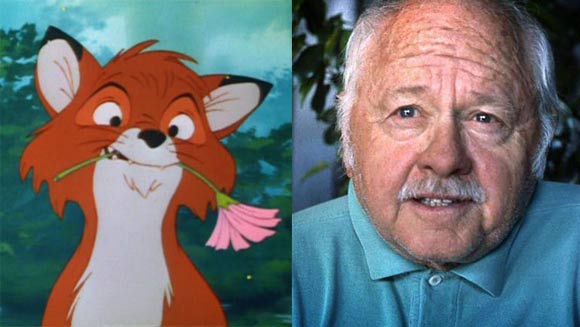

Casting for many parts was easy for the older Disney hands; they tended to go with known quantities that they had used before. Pat Buttram, who had limned other Disney voice roles by that time, was cast as the old dog Chief. Paul Winchell took over the role of the dim woodpecker Boomer. And Mickey Rooney won the lead role of Tod, the hero fox.

Rooney was a supple, versatile actor. He had recently completed a supporting role as Helen Reddy’s father in Pete’s Dragon, and he now segued to the small recording stage next to the studio theater to play Tod. If you wanted him to play a line sad, he could give it to you wistful and breathy, or deliver the words in a hoarse, choking sob that made you believe he was in black despair.

On the recording stage, Mr. Rooney was focused, responsive, and all business. But at lunch afterwards, it was something else again. When the writers and directors sat eating with him in the executive dining room, he talked non-stop about old Hollywood, movie shoots, stage work and ex-wives (seven in all.) And when I say non-stop, I mean like nobody else could get a word in sideways. (All we were required to do was smile and nod.)

During one lunch, CEO Ron Miller walked in, spotted Mickey, and asked how the current Mrs. Rooney was faring. Mickey’s head came up from his soup and he said, “Not good, Ron. We’re getting a divorce.”

A joke, which triggered mild laughter. Ron Miller knew it was comedy, and his smile got wider.

“Oooh. It was a long one this time,” Miller said.

When Mickey was talking, he wasn’t happy when someone challenged any of his sweeping assertions. One noontime when he was regaling us with tales of movie-star dating in the 1940s, he said, “You gotta understand, back then if you went to bed with a woman, you MARRIED her.” I made the mistake of blurting out, “Oh come ON,” which earned me an angry glare.

“No! You did. You really did. I’m not kidding”

After that, I had the sense to keep my flapping mouth shut.

Voice sessions were always exciting, if a bit nerve-wracking. Sequence boards would be hauled to the stage and the sequence director would walk the actor or actress though all the story points, all the antics of the character that the voice talent was portraying. The actor got a good sense of context, as well as the character’s point of view and general attitude. Seeing the body language in the story sketches provided a boost to the vocal performance.

Different actors had different approaches. Pat Buttram, with a long career as a comic actor and in-demand after-dinner speaker (not to mention his extensive career as a side-kick to Gene Autry) liked to joke things up and tell stories. Sandy Duncan (voice of Vixie, Tod’s love interest) wanted to get the character’s motivation down and nail the line.

And Pearl Bailey’s modus operandi was to project personality. She was as outgoing and ebullient as any mortal could be, and she was that way during, between, and after recording sessions. One afternoon during a break, she got the crew laughing over a funny anecdote about one of her network television appearances. I was sitting next to her on a stool, and when she got to her punch line, she broke into guffaws, grabbed my head, and mashed my face into her cleavage.

Happily, I had learned from my Mickey Rooney lunches, and had the presence of mind to stay quiet while gulping air through the side of my mouth.

Art Stevens and the other directors liked Ms. Bailey’s performance, but there was an extended exchange between Big Mama and the fox that Art wanted changed. Specifically, he wanted to alter half of it, keeping Pearl’s recorded lines but rewriting Tod’s as-yet-unrecorded dialogue. We spent a long afternoon rewriting one half of the characters’ back-and-forth, and I teed up multiple variations of Tod’s responses, shuttling them between different directors until the dialogue was nailed down.

The last voice role to be cast was the adult hunting dog Copper. Young Mr. Feldman owned the kid version of the dog, but the adult side of the part was nothing but temporary scratch track, and it was starting to be a problem. Sometime before, Woolie and the other directors had been impressed with veteran actor Jackie Cooper’s audition (and it would have been interesting to have two child stars from the 1930s in lead roles). But Mr. Cooper wanted more money than the studio was willing to pay, so it was adios, Jackie.

Time continued to tick away. Scene and sequences were stacking up, and the directors were starting to get uptight. When Art was about ready to pull his hair out, Kurt Russell came in to read and nailed the role. Kurt was shooting his Elvis made-for-TV biopic at the time, and arrived on the recording stage sporting a white sidewall haircut for his Elvis-in-the-army scenes. He was prepared, energetic, and highly cooperative, and he went through more than half the picture in a single afternoon.

It took only one more recording session for Mr. Russell to finish the job. By that time, production flow had gotten mostly back to speed and everybody could see how The Fox and the Hound’s storyline was coming together.

But there was still one more issue that was driving some of the younger Disney staff (including me) to distraction.