‘Mouse in Transition’: Larry Clemmons (Chapter 2)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition will be published every Wednesday on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

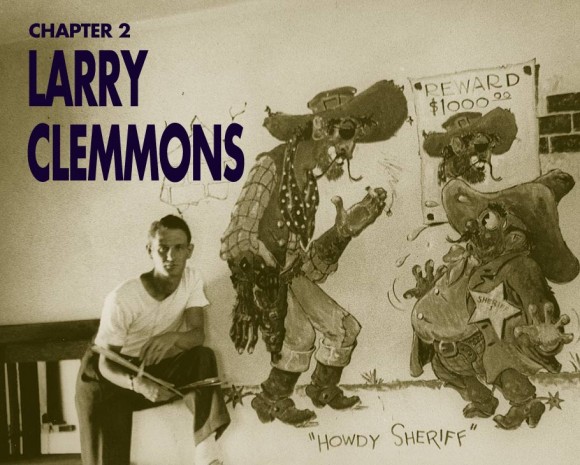

Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Disney’s head animation writer in 1977 was cartoon veteran Larry Clemmons, who had first been hired at the studio in 1930. At the time of his hiring, he was a Yale graduate with a degree in architecture, but an Ivy League education was of little value in 1930 when the economy was collapsing…and few buildings were being erected.

So Larry took the job he could get: work as an in-betweener at Walter Elias Disney’s Hyperion Studio. He soon climbed his way up to assistant on Mickey shorts, and later moved to Ward Kimball’s unit and the Disney story department. When World War II happened, Larry left the studio and decamped to the Midwest, where he wrote technical manuals for wartime manufacturing plants.

But Mr. Clemmons hadn’t given up on show biz. He free-lanced in radio, and at the end of the war, landed a job on Bing Crosby’s prime-time network radio show, where he spent nine happy years writing weekly scripts for Bing and assorted guest stars. When the radio gig ended, he returned to Walt Disney Productions as a writer and segment producer on The Mickey Mouse Club. And when that assignment wrapped up, he wrote Walt’s spoken intros for the television show entitled Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color.

Walt must have liked Larry’s work, because a few years later, when the Writers Guild went on strike, he saved Larry from walking a picket line by switching him to animated features…and another union’s jurisdiction. (Or maybe he just didn’t want Mr. Clemmons outside the studio gates with a sign saying “On Strike!”)

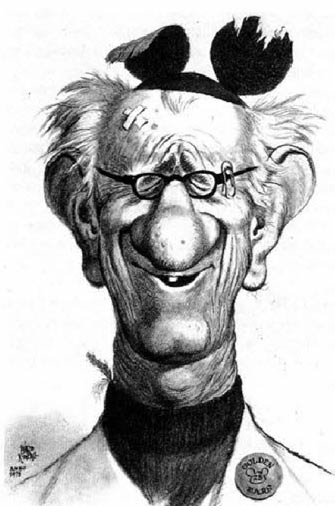

Don Duckwall introduced me to Larry halfway through my first week of “permanent” employment. He had gray hair, a generous nose, and a wry sense of humor lightly seasoned with cynicism. After a year of working together, he provided an example of where the cynicism came from: “All this crap about the Golden Age of animation? Back in the thirties? It wasn’t MY Golden Age. It was the middle of the damn depression. There weren’t any damn jobs. And there I was, doing breakdowns on a damn Donald Duck short. And then the production manager would walk in and say, ‘We gotta get this picture out! Who wants to come in Saturday and work?’ If you wanted to keep your job you raised your hand and shouted how much you wanted to spend your Saturday there. For no pay. Like I say, it wasn’t MY Golden Age.”

Larry also regaled me with tales from his radio days, about doing live remotes at March Air Force Base with his boss and Bob Hope, where he scrambled through the audience retrieving script pages when Bob didn’t like Crosby’s witty ad libs and threw Bing’s entire script out into the front-row seats.

But all that was later. At our first meeting, he greeted me cordially and said that Woolie Reitherman, leader of the animation department and director on every animated feature since Sleeping Beauty, was holding a meeting in a downstairs story room and wanted the whole story crew there.

So down we went. Wolfgang Reitherman, tall, weathered, and more rugged-looking than John Wayne, was holding forth in a big story room in D wing, with a dozen story artists arrayed around him in swoopy, leather-and-wood chairs. He shook his head.

“Guys, The Rescuers is done now, but it cost seven and a half million dollars. Seven and a half MILLION dollars. We can’t go on spending that kind of money on these things, we just can’t. We gotta find ways to do them cheaper.”

Everyone bobbed their heads in solemn agreement. I was new, and had no freaking idea what an eighty-five minute cartoon feature was supposed to cost, but I nodded my head, too. When in a movie studio, the safest approach is to follow the behavior modeled by the locals.

In retrospect, of course, the seven and a half million dollars was a bargain. Every Disney animation feature since has cost more, way more. But who the hell knew THAT was the budget trajectory in 1977?

The story department had a half-dozen storyboard artists working on the next Disney feature, a tale about a fox and a hunting dog called, naturally enough, The Fox and the Hound, and Woolie had already assigned artists to different sequences, even though there was little more than a sketchy story outline. Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, the last of Walt’s original supervising animators, were busy in their first-floor offices designing characters and doing “experimental animation,” figuring out how the lead characters might act and move.

Meanwhile up on the third floor, Larry was turning out script pages and test dialogue, running them by Woolie, then recording the dialogue across Dopey Drive on a small soundstage next to the studio theater. Larry’s pages were formatted like a radio script, with characters’ names off to the side and dialogue arrayed in large blocks of type. At the time, I thought this was the way all scripts looked. Only later did I realize that Larry had brought his format from a decade of radio comedy-writing back with him to Disney.

Larry’s scripts didn’t contain much narrative description because Larry focused on dialogue. He knew how to set lines up and pay them off, knew how to make the words “ping” against one another. Just then he was writing “wild lines” for Tod the fox and Copper the hound dog — as puppies. Woolie was testing lots of kid actors, searching for the right mix of voices for the new animated feature.

Since Larry was now my immediate supervisor, I showed him everything I wrote, and also tagged along with him to the recording stage when the kid actors showed up to read his dialogue. Woolie was always in the booth with the engineer; Larry stayed down on the stage floor with the seven and eight-year-old actors, prompting them with line readings and doing a lot of the heavy directorial lifting.

Larry Clemmons was a solid voice director. If a kid was listless and flat, Larry demonstrated how to goose the line: “John? Try it this way: ‘I’m a hooouund dog.'” Or if one of the young actors was over the top, Larry knew how to reel him back in. Instructions, followed by the modeled line (Mr. Clemmons knew what he wanted), then a bit of praise. Worked like a charm.

Various children paraded through the recording stage, agents and mothers in tow. Larry and Woolie honed in on two boys with quirky but oddly magnetic voices. Larry wrote more lines, and the pair was brought back for additional readings. The results weren’t part of an existing sequence, but Frank Thomas heard the wild lines, got inspired, and commenced thumbnailing a long stretch of the young dog and fox meeting for the first time, getting in trouble together. Within a couple of months, Frank animated action and business containing so much personality and life, that every foot of Frank’s test animation…and Larry’s dialogue…ended up in the feature. A year later, Frank and Larry had both retired.

Watch Larry Clemmons pitch a scene from The Rescuers. Clip via Andreas Deja.