‘Mouse in Transition’: Goodbye Disney (Chapter 18)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition are published on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Chapter 3: The Disney Animation Story Crew

Chapter 4: And Then There Was…Ken!

Chapter 5: The Marathon Meetings of Woolie Reitherman

Chapter 6: Detour into Disney History

Chapter 7: When Everyone Left Disney

Chapter 8: Mickey Rooney, Pearl Bailey and Kurt Russell

Chapter 9: The CalArts Brigade Arrives

Chapter 10: Cauldron of Confusion

Chapter 11: Rodent Detectives and Studio Strikes

Chapter 12: Disney Dead-Ends & Lucrative Mexican Caterpillars

Chapter 13: Basil Kicks Into High Gear

Chapter 14: “Call Us Mike and Frank”

Chapter 15: The Arrival of Jeffrey Katzenberg

Chapter 16: A Gong Show with Eisner and Katzenberg

Chapter 17: The Trials of Oliver & Company

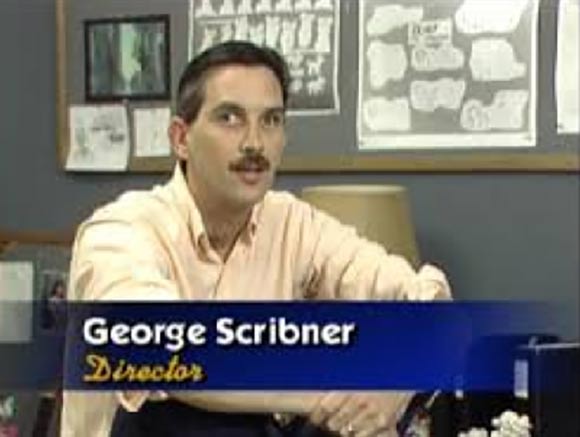

Back at the studio on Monday, the universe had changed. Pete Young was gone. George Scribner and Richard Rich, the two directors assigned to Oliver, were taking over as the creative leads on the movie. But it was Mr. Scribner–the recently promoted Black Cauldron animator–who seemed to have the ear of management.

The big executive change was the new department head that Roy Disney had picked to manage day-to-day operations–a young man with energy to burn named Peter Schneider. Peter had thick brown hair and a bantamweight’s physique. He’d worked on the arts committee of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, been recommended by the Olympic’s executive director, and Roy had given Peter his stamp of approval. And now here Mr. Schneider was, holding meetings with staff and making decisions about where feature animation would be going. He was focused and intense, but there was a lot of that in the ranks of newer executives.

The second week I was back, I got into an argument with Peter about Oliver’s story and character development. Not a brilliant tactical move, but I was always too mouthy for my own good. By contrast Bruce Morris, one of the savvier young board artists, gave Peter a memo filled with helpful observations and suggestions. Bruce was soon promoted to a management position.

As for slow-witted me, I could feel the ground shifting under my stumbling feet. Jeffrey and Michael hired a young writer fresh out of college to come in and work on Oliver, and I soon found myself with less to do. (An ominous sign.)

Meetings on the picture started being held without my participation. But I wasn’t the only veteran that was experiencing this. Rick Rich wasn’t getting invited to story sessions either, and one day when I noticed everyone else was closeted in yet another meeting, I strolled over to Rick’s office and stuck my head through his open door. He was bent over a storyboard, and looked up. I grinned sourly.

“There’s a story meeting going on without us, Rick,” I said. Think that means anything?”

He gave me a blank stare and said nothing. But then, there wasn’t much to say. When you’re excluded, it’s obvious.

I kept writing outlines and sequence scripts, kept showing them to George and Rick. It was like dropping sheets of paper down a deep well. I never got notes or, for that matter, any reactions. But it wasn’t all non-communication. One day George came to my office with a fresh idea for the title character that he and the new writer had cooked up. He was excited.

“We figured out why Fagin wants a grubby little cat like Oliver in his gang of dogs,” Scribner said. “It’s always bothered me, but now we’ve licked it.”

“So why does Fagin want him?” I asked.

“Oliver’s a rare, Asian cat. Worth a lot of money. Only Fagin doesn’t know this because the cat’s caked with mud. Then Oliver gets caught in a rainstorm and the mud washes off. And Fagin realizes that Oliver is valuable. And that he can hold the cat for ransom.”

I thought about the new story wrinkle for fifteen seconds, and shook my head. “It’s weak, George. The cat doesn’t do anything. He’s a prop. He’s supposed to be the hero, to make things happen.”

George frowned. “I think it works pretty well. It solves problems.”

“Hey, you’re the boss George. I’ll do whatever you want. You like the approach, that’s good enough for me. I’m happy to work on it.” (When in disagreement with a superior, it’s often useful to defer to the superior. Slowly I was learning. But I wondered if it was too little, too late.)

Mr. Scribner left without tipping his hand whether he wanted me to work on the new idea or not. (I suspected not.) But it turned out not to matter. A couple of weeks later, George rolled out the new approach to Jeffrey Katzenberg, who shot it down. A couple of artists informed me that Jeffrey had called the “cat covered with mud” idea stupid.

Thanksgiving came and went, then Christmas jingled by. Many days I felt as if I was underwater, struggling to come up for air. Every once in a while my brain operated normally, and I convinced myself I was accomplishing useful work. This was mostly an illusion.

The day after New Year’s, I discovered that the new writer had gotten a new company computer to replace his personal Mac. I was limping along with a clunky Kaypro computer I’d used for years, and decided I needed a company computer too. So I asked production manager Don Hahn (soon to become the producer of blockbuster animated features) if I could get a new computer like the other writer had.

We were standing at the side of a meeting room. Don looked at me. Opened his mouth. Closed it. Finally smiled and said, “Sure.”

Don’s demeanor and body language should have been a tipoff, but I was by then living in a cloud of fear and trepidation, of wondering what the hell was going on with my decade-long Disney career. Telltale signs eluded me.

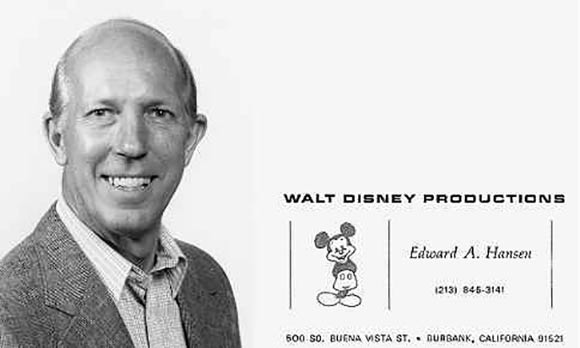

The next day the cloud lifted. Ed Hansen pulled me out of a department meeting, walked me down to his office, and sat me in the visitor’s chair. He plunked down behind his desk and said in a husky voice, “Steve? You and I are going to be parting company.”

Depression and anger, mingled with the relief of finally knowing my fate, flooded over me. I pulled the corners of my mouth up in the facsimile of a smile and said, “Ah.”

Much later, I thought of a snappy comeback: “Parting company, Ed? The hell you say? You’re leaving Disney Animation? After all these years?” But at that moment I sat numbly, still and silent as a statue, as Ed explained the company was paying me some separation money and extending my benefits as it dropped me over the side of the S.S. Disney.

I traipsed back to my office and soon found out that I wasn’t the only employee being cut loose that day. Director Rick Rich was also laid off, along with two assistant directors.

Word circulated like a summer brush fire that the four of us had been made history, and a few employees trickled in to say they were sorry to see us go. Board artist Doug Lefler took pity on my sorry backside and invited me out to lunch, telling me that though the Disney door was closing, others would swing open. (Just then I fervently wished that somebody…anybody…could have tipped me off what they were.)

It took a couple of days for me to load papers and other rubble collected over nine and a half years of employment into boxes, and from there into the trunk of my car. In the hallway, people smiled, mumbled “good luck,” and hurried on their way. I got a taste of what it was like to have a terminal disease people were anxious to get away from.

As I packed up my last box, George Scribner came into my empty office. His face was pinched with concern. He told me how sorry he was I was leaving. “I had no idea management was planning to do this, to let you go. It’s a shock. But good luck. Really.”

George shook his head over the shock of it all, then shook my hand and exited. The sighs and chin wagging seemed a bit hollow and forced to me. But maybe I was too cynical. Maybe George felt badly after our argument about the “valuable cat” idea, and he was trying to balance the scales.

I turned in my employee ID. On my way out of the studio for the last time, I dropped in on Vance Gerry. Vance had already offered condolences in the hall, but I wanted to stop by his office for a last goodbye. Like always, he was bent over his desk drawing. He looked up and swiveled around.

“Hey, Steve. You leaving?”

“Yeah,” I said.The last of everything is out in the car. But I had a question.”

“Ask away,” he said.

“George talked to me, said he was surprised about my layoff. That sound right to you?”

He smiled. “Close the door,” he said.

I closed the door.

“Peter Schneider held meetings about your layoff weeks ago. George was there, discussing you and Rick and the others being let go, when it was going to happen.”

Layoff meetings. That would explain Don Hahn’s pregnant hesitation when I asked for a new computer. And why Rick and I had been treated like lepers the last several weeks. Don (and many others) knew my time was limited. Who’d want to order a new computer for one of the walking dead? Or invite a corpse to a meeting where creative decisions were being made?

“Good to know,” I said.

I departed Vance’s office and walked to my car. I shouldn’t have been surprised with George’s behavior. He liked to be liked, to be considered a “good guy.” Don’t we all? Plus the animation department’s culture was changing. No longer was it a laid-back cartoon studio, a small island of backwardness populated with people who asked: “What would Walt do?” Now it was run by mainstream Hollywood players with sharp elbows, Alpha personalities, and their eyes on the big, box office prize.

It had been a quick and busy ten years, filled with creative ups and downs, filled with change. When I arrived, Disney Feature Animation had been populated by veterans with vivid memories of Snow White and Walt pacing the halls. When I left, the old-timers were gone and artists and executives in their twenties and thirties ruled the roost.

At the time, nobody knew just how different Disney Animation would become, but it wouldn’t take long to find out. Even as I drove away, Ron Clements and John Musker were starting work on The Little Mermaid…

Mouse in Transition has been released in paperback and e-book formats from Theme Park Press. In addition to Hulett’s on-going narrative, the book contains a foreword by Disney director John Musker, a half-dozen interviews with Disney old-timers, and biographical sketches of Disney animation staffers who worked at the studio in the 1970s and ’80s.