‘Mouse in Transition’: Disney Dead-Ends and Lucrative Mexican Caterpillars (Chapter 12)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition are published weekly on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Read Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Read Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Read Chapter 3: The Disney Animation Story Crew

Read Chapter 4: And Then There Was…Ken!

Read Chapter 5: The Marathon Meetings of Woolie Reitherman

Read Chapter 6: Detour into Disney History

Read Chapter 7: When Everyone Left Disney

Read Chapter 8: Mickey Rooney, Pearl Bailey and Kurt Russell

Read Chapter 9: The CalArts Brigade Arrives

Read Chapter 10: Cauldron of Confusion

Read Chapter 11: Rodent Detectives and Studio Strikes

Developing viable feature projects is the life-blood of every animation studio. There are no hot, bankable stars that carry an animated movie (executive thinking to the contrary), and no dazzling visual effects, since the animation, lighting and “final look” are the visual effects. There is only the story, characters and dialogue, along with the execution of those things, to lift a full-length cartoon to the heights.

Animated features often spend years in development. Disney’s Peter Pan had work done on it in the 1930s; Lady and the Tramp meandered through the Disney story department for a decade and more before reaching the silver screen. More recently, the Mouse’s feature Tangled went through a dozen years of story permutations before coming out as a CG feature. Wreck-it Ralph was started, then stopped, then started again, finally being released in 2012.

When I arrived at the studio in the Seventies, Woolie Reitherman led the story development team, but ideas percolated from a variety of sources. Story artist Fred Lucky had brought in The Rescuers, and was put to work developing it. In the early stages the picture was considered a lower-cost, “B” project prior to morphing into a full-scale, mainstream production. It ended up as Disney’s most successful animated feature since The Jungle Book.

Shortly after I got to Walt Disney Productions, I thought it would be great to make a cartoon feature starring Mickey, Donald, and Goofy. I was a big fan of The Thief of Bagdad with Douglas Fairbanks, and came up with a story of the trio in an Arabian Nights adventure. I even got animator and designer Andy Gaskill to create a visual of Mickey on a flying carpet.

There was zero interest from studio management, but it was fun to dream.

The whole time I was at the Mouse House, I never lost my yen to do some kind of project with Mick-Don-Goof. Years after the Arabian Nights idea, Pete Young and I pitched a storyline starring the threesome in Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers. We got an okay to develop the novel into a feature and even had a producer attached to the project.

On fire with enthusiasm, we looked at different Musketeers films and broke down the various plot points. Pete began blocking out character bits, action, and different gag possibilities. Forward!

Then I made what turned out to be a mistake. I brought in a 16mm print of the Don Ameche musical-comedy version of The Three Musketeers, a lower budget 20th Century-Fox film directed by movie veteran Allan Dwan back in 1939. It co-starred the Ritz brothers as inept imposters of the King’s Musketeers and was mildly diverting, but Pete didn’t think it was a good blueprint for the way we should go with a storyline. He wanted to use more of the book.

Our producer, however, thought the Ameche film was wonderful and wanted us to follow its plot and character development beat for beat. The three of us had polite discussions about it, then less polite arguments. One day behind closed doors Pete railed at me: “Why did you bring that damn movie in?! Now we’re stuck with that stupid plot line!”

Work continued on Musketeers for months, but development never really took flight. Pete and I tugged the story one way, and the producer yanked it another until the project slowly, fitfully sputtered out. (But obvious marriages never die. Years later, one of the Disney Company’s other divisions resurrected The Three Musketeers and created a Mickey-Donald-Goofy feature unrelated to the work we had done. The resulting movie also had little connection to the Dumas novel.)

I had my third shot at pitching a Mickey project when Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg arrived on the lot. At a large pitch session I proposed doing Kipling’s The Man Who Would be King as a vehicle for the company’s corporate symbols, and Katzenberg asked to see a treatment. So I quickly wrote one. Sadly, my sterling prose did not entice Jeffrey to develop the property further.

Some characters, however, DID enjoy a successful revival. Shortly after the cartoonists’ strike, Pete Young pitched a Winnie the Pooh featurette to management, which flashed a green light for development. (Pete had a near-perfect record getting the brass to okay projects). He had already carved out two entertaining sequences from the Milne books; he proceeded to draft me, Ron Clements and writer Tony Marino to help him flesh the episodes out.

Of all the development work I did at Disney, the featurette entitled Winnie the Pooh and a Day for Eeyore was the fastest and smoothest I encountered. There were no angry arguments; everyone just pitched in and kept the creative ball rolling. Within weeks the entire picture was up on storyboards; Ron Miller reviewed what we’d done and quickly approved it.

The difficulties commenced near the end of the boarding project. The studio decided to job the featurette out to a small Los Angeles animation studio, and Ron Clements was horrified.

“How can they DO that!?” he complained. “Quality will be terrible! They’re just trying to save money!”

It was, in fact, exactly what the company was trying to accomplish: make a theatrical cartoon at a cut-rate price. Ron continued to be unhappy about the production all through its making. When the featurette was released in March 1983 with a re-issue of The Sword in the Stone, he demanded his name be taken off the credits, and the studio complied.

Pete, Tony Marino, and I kept our names on. We weren’t as high-minded as Ron. We decided if we had earned a screen credit, we wanted a screen credit, even if the featurette to which our names were attached was Disney Animation’s first sub-contracted work in fifty years.

But there was a lot of development that didn’t involve established Disney characters. Studio veteran Mel Shaw supervised work on a handful of shorts based on Hans Christian Andersen stories. (John Lasseter and I both worked on Andersen’s The Nightingale…for all of three weeks.)

And I spent time writing a treatment on the fairy tale Beauty and the Beast. I watched the Jean Cocteau picture, researched the original story, and shared my resulting handiwork with some seasoned Disney story artists. After the veterans read it, five of them sat down with me in a second-floor story room to analyze the treatment and its potential.

Vance Gerry was on my right; a slender, gray-haired board artist named Al Wilson sat on my left. Al was high-strung, with a nervous laugh that fit nicely with a stammer reminiscent of Jimmy Stewart’s. He held up the treatment and looked at me.

“I…don’t know. I…Steve? You call this good? You call this interesting? I don’t see it. I don’t really understand it. I…”

“What are you trying to get at, Al?” Vance said. I noticed that Vance’s face was darkening.

“It…it just kind of lies there. I…I just don’t get it. I mean, does Steve think this is any good?”

Vance exploded. “Goddamnit, Al! I’ve listened to your negative shit for years! And I’m sick of it! Just shut the hell UP!”

Vance was yelling, his face bright red. I had worked at Disney for seven years and never, ever seen the smiling, easy-going Mr. Gerry behave like this. We all gaped at him, but Al’s mouth was open the widest.

“Vance? I…I didn’t mean it was…was horrible, I just…”

“We all know what you meant, Al!” Vance shouted. “And just STOP IT! I can’t stand it anymore! Shut UP!”

Al shut up. I decided Vance must have had some ongoing issues with Al Wilson, but I didn’t ask what they were. Better to keep some doors to the past unopened.

I don’t remember how the rest of the meeting went, although I do remember that Al Wilson became very subdued. Vance’s outburst is the only part of the meeting that remains vivid. My treatment, like lots of ideas that bounced around the studio, soon sank without a trace. Of course eight years later, when I was long gone, the fairy tale was looked at again and made into a blockbuster hit.

Good ideas never die. Only so-so movie treatments.

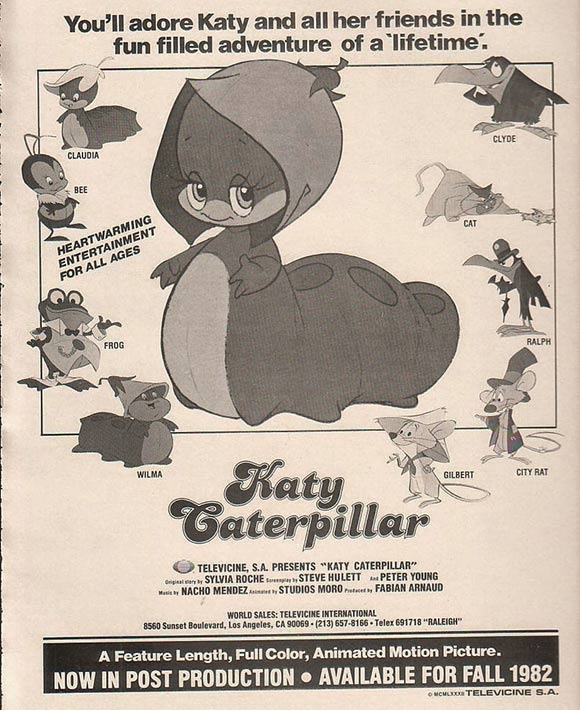

But the most pain-free development deal that Pete Young and I ever did wasn’t on a Disney feature, or some stretched-out project that ultimately went nowhere, but a seventy-five minute non-Mouse cartoon entitled Katy Caterpillar. Katy, it turned out, was a popular character in Mexico and South America, and she was controlled by the state-owned entertainment conglomerate named Televicine, headquartered in Mexico City. Televicine, as it happened, wanted to leverage its already successful property into a theatrical animated feature.

One bright day in the spring of 1983, an agent repping the Latin company called me up to see if I might be interested in writing on Katy’s first feature film. (Televicine wanted Disney staffers to do the work, and the first Disney employee they had approached had been too busy to take extra work on.)

Always interested in extra cash, I said that I would be happy to pitch in. One phone call later, I was attached to the project. A couple of phone calls after that, I had talked Televicine into adding Mr. Young to the creative team.

The Mexican conglomerate wanted to meet with us, so Pete and I flew to Houston, Texas, for a story session with Televicine executives. The U.S. was just then climbing out of a recession, but Houston, deep in the oil patch, was already in the middle of a long boom. Pete and I were put up in a flossy hotel that anchored one end of the biggest shopping mall either of us had ever seen. (The place was so large, a 7-year-old who wandered away from his parents would have quickly ended up with his face on a milk carton.)

We spent most of a Saturday afternoon in Televicine’s tenth-floor suite going over story beats and characters that one of the movie’s producers, a pleasant dark-haired woman named Silvia Roche, wanted in the picture. (The lady was the caterpillar’s creator, and insisted that Katy’s signature line of “Whippity pow!” be sprinkled liberally through the screenplay. Pete’s eyes got a faraway look, but we both nodded agreement. When you’re the new hired hands, you do what the producer wants.)

The two of us flew back to Burbank. And for the next few months, in between working on hair’s-breadth escapes for a sleuthing British mouse, we created adventures for a cute, girl caterpillar. Pete focused on beat boards while I wrote the screenplay. When we finished both, we took a long, bumpy flight to Mexico City and delivered our finished work to the waiting hands of Silvia and her executives.

Televicine seemed happy with it. They put us up at a four-star hotel, had a corporate vice-president give us a personal tour of the city, and saw to our every need. But when the picture came out a year later, Pete and I both felt let down. Katy had the plot and action we’d devised, but there were no subtleties to the picture. Mostly it was a low-budget cartoon cranked out by Moro Creative Associates in Spain, and looked it.

But at least the money Televicine paid us was good.

Then things got more interesting, in the Chinese sense of the word. A month after Katy’s release, we discovered that Disney CEO Ron Miller would be taking a look at the film, and Pete had a partial meltdown. (“Oh shit! That picture is low-rent stuff! What’s Ron going to THINK?!”) But after a couple hours of hand-wringing, we decided the best defense for both of us was a breezy, nonchalant attitude: “Okay, it isn’t Disney quality, but so what? It was a job of work and we got paid.”

We toughed out a Friday afternoon screening with the Chairman of the Board and other Disney executives, squirming in the back of a third-floor screening room as Ron watched the project on which two of his employees had moonlighted. When the lights came up, he spent three minutes ribbing us about the movie and then mercifully departed. We took the ribbing like men…who’d had Novocaine injected into their frontal lobes.

Afterwards, Pete was philosophical about the experience. He wished that the feature had been stronger, but he was happy about the fee (a third of our meager annual salaries), and once he realized the outside project hadn’t damaged him with the Big Boss, he could even joke about it.

“At least the feature got made, Hulett. That’s more than you can say about lots of story development we do around HERE.”

Mouse in Transition will soon be out in e-book and paperback formats from Theme Park Press. In addition to Hulett’s on-going narrative, the book will contain a foreword by Disney director John Musker, a half-dozen interviews with Disney old-timers, and biographical sketches of Disney animation staffers who worked at the studio in the 1970s and ’80s.