Behind The Scenes of ‘Mr. Carton’: The Animated Series Made With a Game Engine

We all know that producing good computer animation can be a lengthy and expensive process. But what if there were ways of speeding up the production time without reducing quality?

French animator Michaël Bolufer has attempted to do just that by adopting the Unity game engine to complete Mr. Carton, a 13 x 2-minute series of shorts. The entire series is available to watch through France Televisions’ Studio 4.

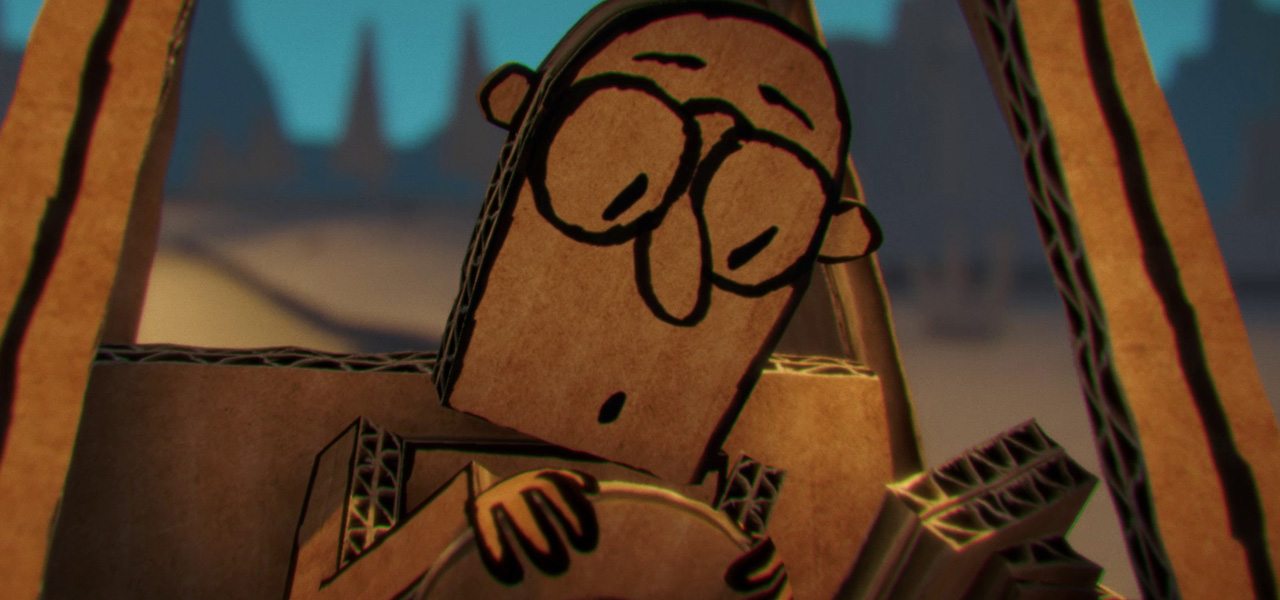

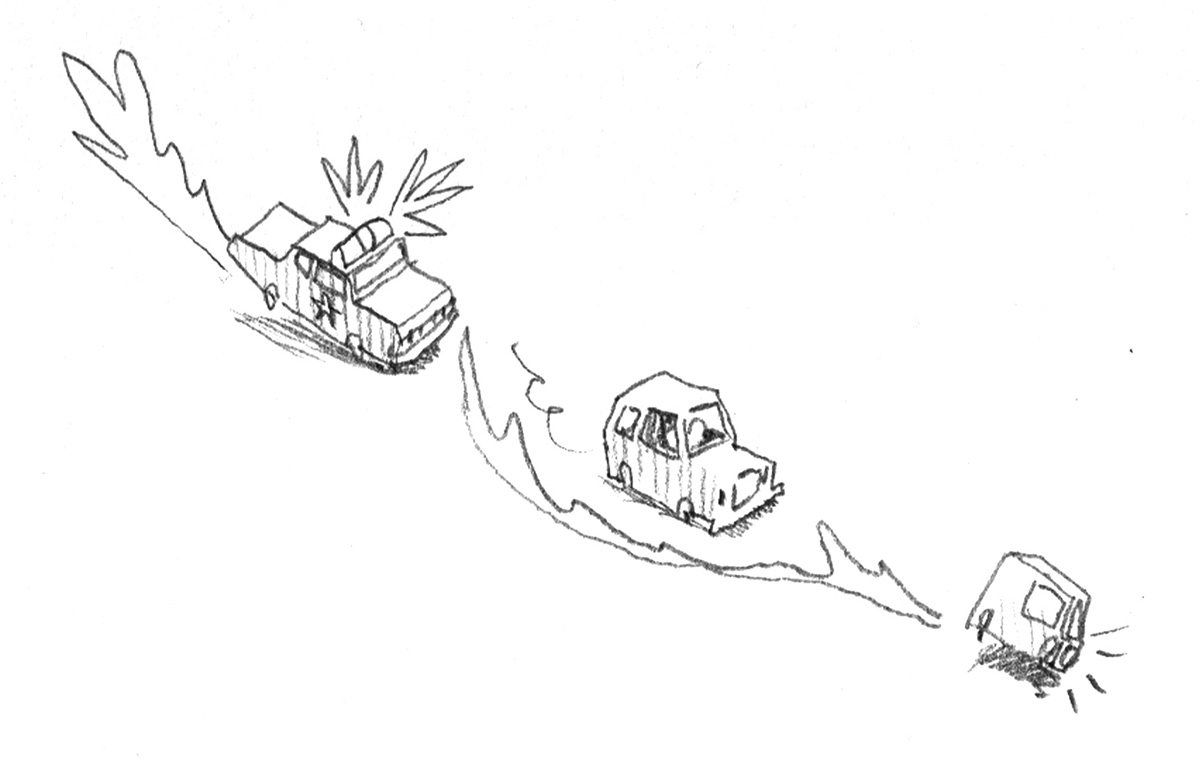

The story of Mr. Carton follows a clumsy driver, in his cardboard-made car, trying to get to the lighthouse at the peak of a mountain. Cartoon Brew spoke to Bolufer about the decisions behind the game engine (i.e. real-time rendering) approach to the show, what challenges he and his team faced along the way, and where he sees the tech being used in animation in the future.

Why a game engine?

Prior to the production of Mr. Carton, Bolufer worked in both the video game and animation industry. During that time, he could experiment with the available tools. With the usual off-line production toolset in animation, Bolufer told Cartoon Brew that he would be “spending time scratching my nose, playing guitar, drawing something on a paper under my keyboard, going to the cafe, waiting for my render to be finished.”

But on games, due to the real-time gaming engines being used, he found he didn’t waste time composing a final image. It provided an immediate result, and one that he could re-render almost instantly if a creative decision changed.

The idea, then, to use Unity in the first place came about after Bolufer had actually developed a teaser in 2012 with other 3D tools. These proved to be slow-going, so he looked instead to the toolset he was using at the time at France’s Atefacts Studios for a racing game. That was Unity.

A team of storyboard artists, modelers, animators, lighters, and compositors is still required to create episodes. Although the cars and world have the appearance of cardboard, they are actually 3D models that make use of photographic textures. Ultimately, a combination of tools has been used on Mr. Carton, including Blender, 3ds Max, Unity for 3d modeling, rigging and animation, Adobe Premiere Pro for editing, and Photoshop for 2D work.

But Bolufer believes that without having Unity in the pipeline, a more traditional approach would have slowed down the production. “We spent something like 21 days per episode, more or less,” he said. “I guess it would have been around 20 per cent more with a classic cg pipeline, and without all the fine tuning we were able to do last minute in Unity.”

Getting up to speed in Unity

For animators who have worked in, say, 3ds Max, Maya, or Blender, is Unity a major change? Bolufer said that he did spend a lot of time learning the software before starting actual production, “creating test scenes, making little games for my two girls, testing assets from the asset store. I needed to have a global view on the tool. I had to be sure not to be on a little cardboard Titanic.”

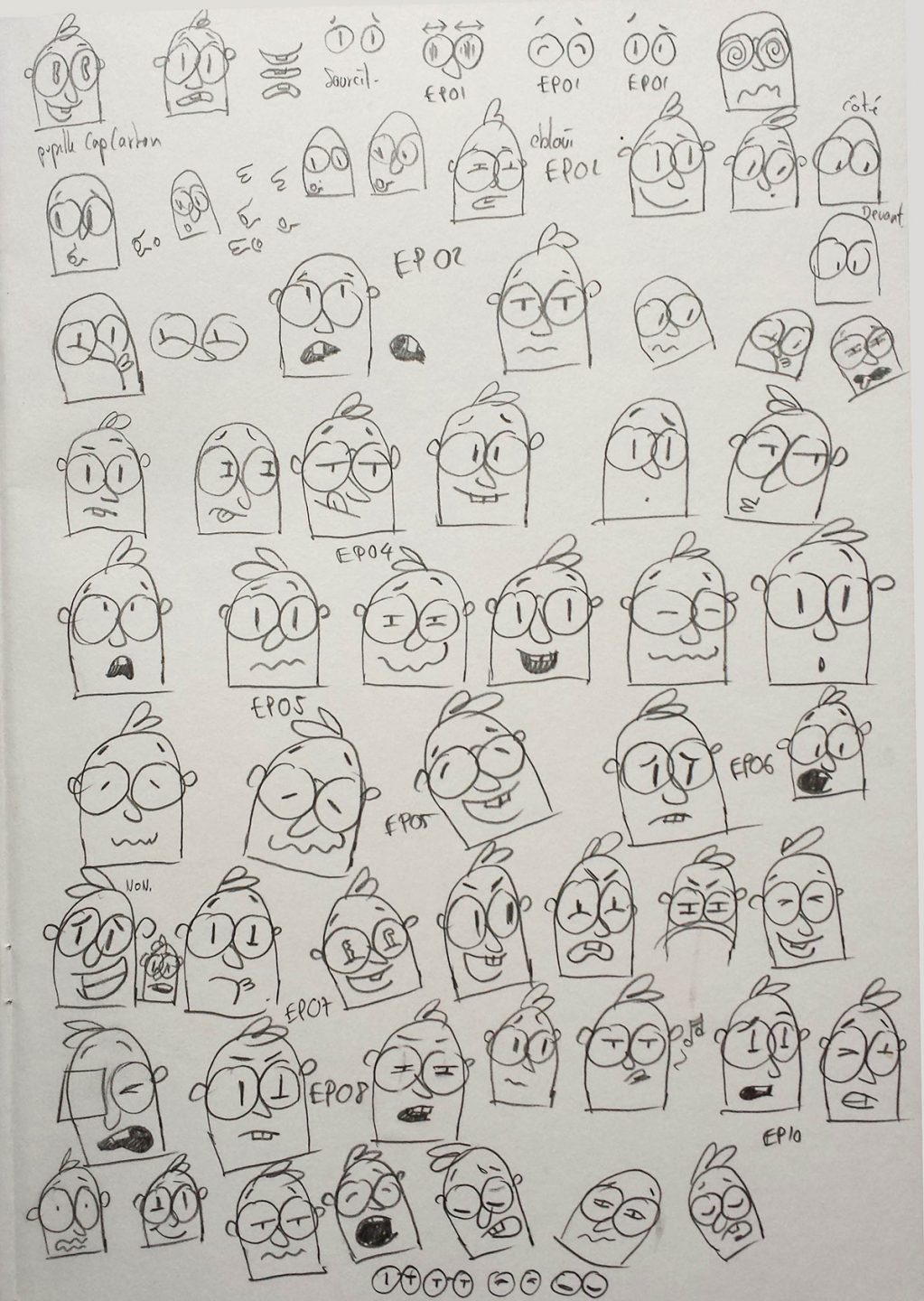

“But,” Bolufer added, “it’s an everyday job, there is always a new thing to explore or a new way to use old things. The most important was to have a story to tell, and a character to play with.”

The main difference between the game engine pipeline with Unity and that of a more traditional offline workflow was mainly in the sequencing stage, necessary to bring together animation, models, cameras, lighting, and compositing.

For that the team used a Unity extension called Flux. “The sequencer is where a big boost, time and creative wise, is happening in a realtime animation production pipeline,” Bolufer mentioned in a Unity blog post interview.

Bolufer says there were “no limitations” in using Unity compared to using a non-real-time approach. And that’s something he suggests bodes well for the use of real-time game engines in other shorts, and even features.

“As long as the team is well structured with game industry and animation leads on each key department, it’s no harder than creating a game,” Bolufer said. “Maybe it’s actually easier because there is no player watching everything in every direction trying to get stuck behind a rock.”

Mr. Carton’s future

The series has now been out for just over a month in France (it’s geo-locked online to that country, although two episodes are available to watch from anywhere). Overseas releases are planned and Bolufer is also hoping to produce a second season and a game. “The game idea was a key reason for using Unity – everything we made is game ready! I already have a fun little prototype of an original car game with Mr. Carton, but we need to find money for this part of the project and we hope that our TV channel, France Television, will soon order the second season.”