Building A Pinscreen: How To Make One Of The Rarest Tools In Animation

This year witnessed a rare event in the animation world: the birth of a new pinscreen. The device will live at the art center La Bande Vidéo in Quebec City, and artists will soon be able to access it via a new residency.

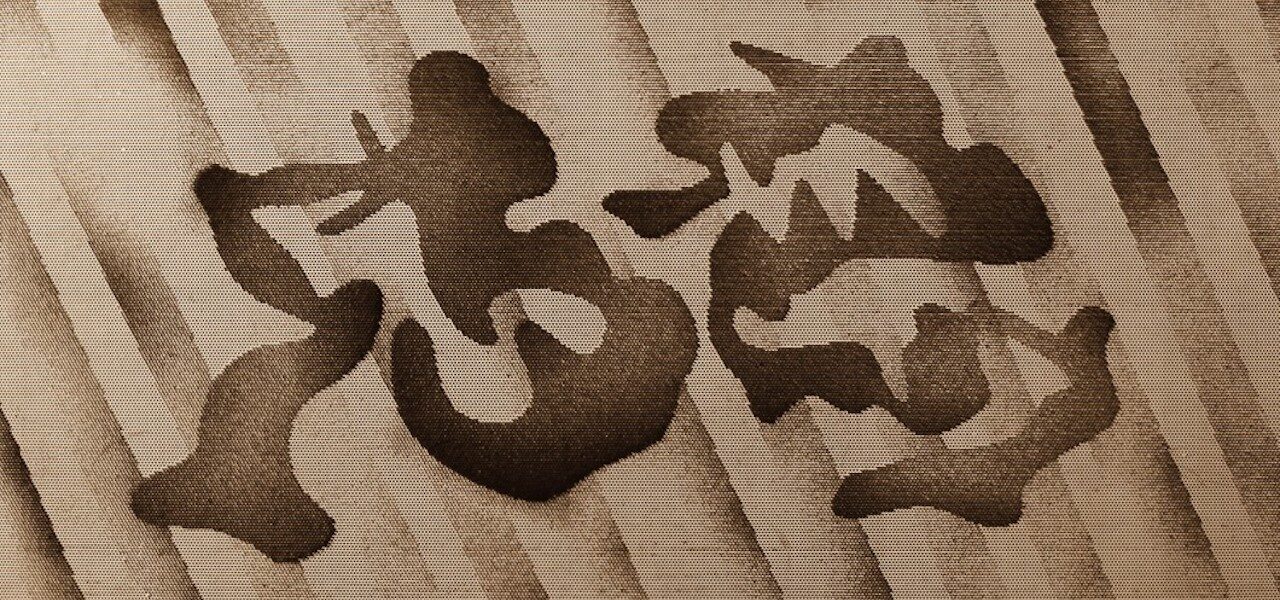

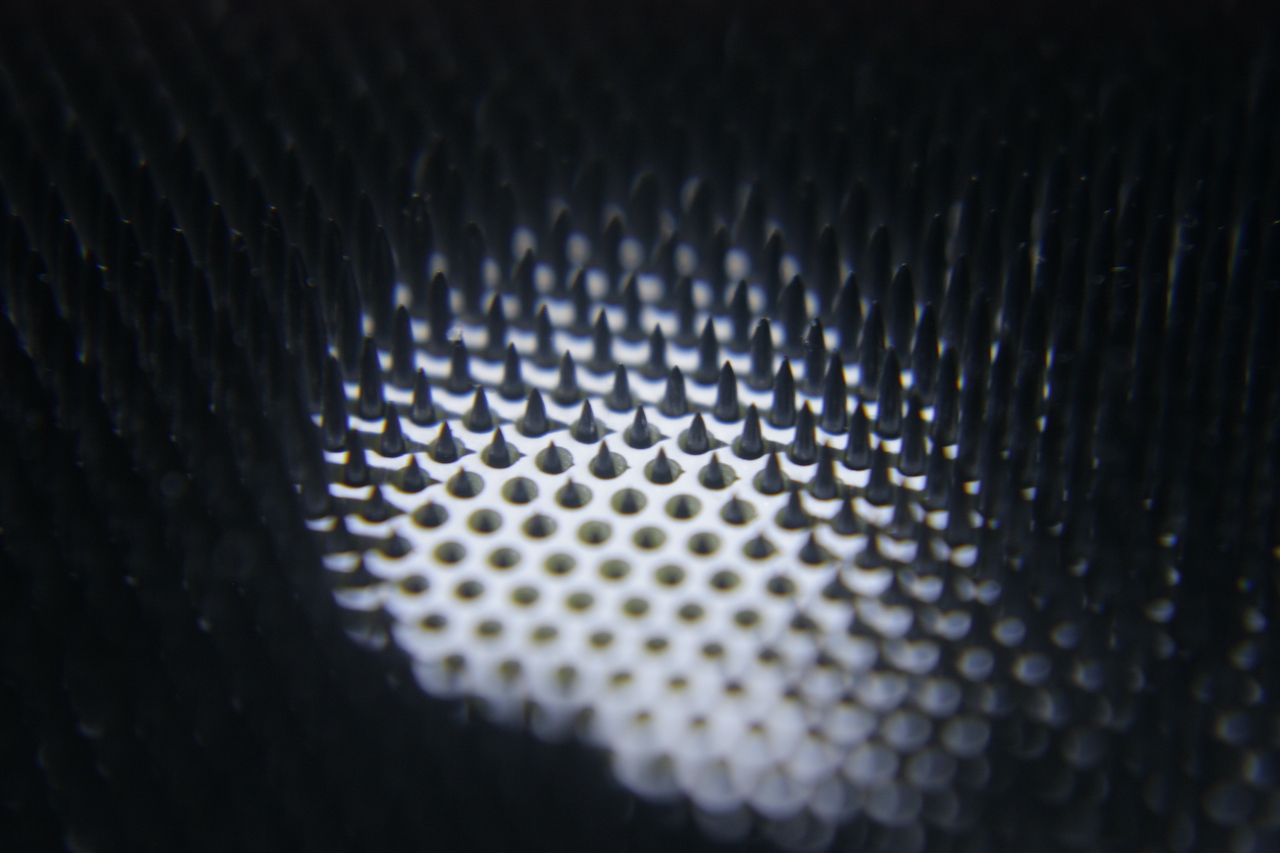

For the uninitiated: a pinscreen is a screen fitted with thousands of pins that can be pushed in and pulled out. Lit from the side, the pins cast shadows whose lengths vary with the degree of retraction. This tapestry of shades creates an image — one frame of an animated film. Invented by Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker in the 1930s, the tool is complicated to build and tricky to master, and as such few have been built since.

The arrival of a new screen is therefore an event. Built by French artist Alexandre Noyer, L’Alpine is only the third full-sized functioning pinscreen in the world. The other two, both Alexeieff/Parker originals, belong to the National Film Board of Canada and France’s film agency CNC.

L’Alpine — the name is a reference to Noyer’s home in the Alps and a pun on “all pins” — has already been sampled by Alexandre Roy, a filmmaker who has worked with a smaller pinscreen in the past. He suggested that La Bande Vidéo acquire a full-sized screen in the first place, and after L’Alpine was delivered, he began working with it this spring.

We spoke to Noyer and Roy about the new pinscreen: how it was made, how it compares to the old screens, and why it feels so good to move the pins …

Building the parts

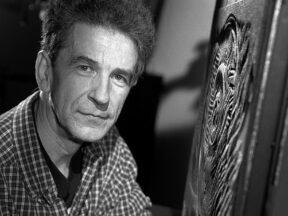

In 2015, Noyer decided to learn how pinscreens work. Denied access to the only two models then in existence, he opted to build a prototype. His resources: a mishmash of books and other texts, online videos and dvds, photos, and help from professionals. He received advice from animators who had worked with pinscreens, like Michèle Lemieux and Jacques Drouin, as well as curator Maurice Corbet and scholar Giannalberto Bendazzi.

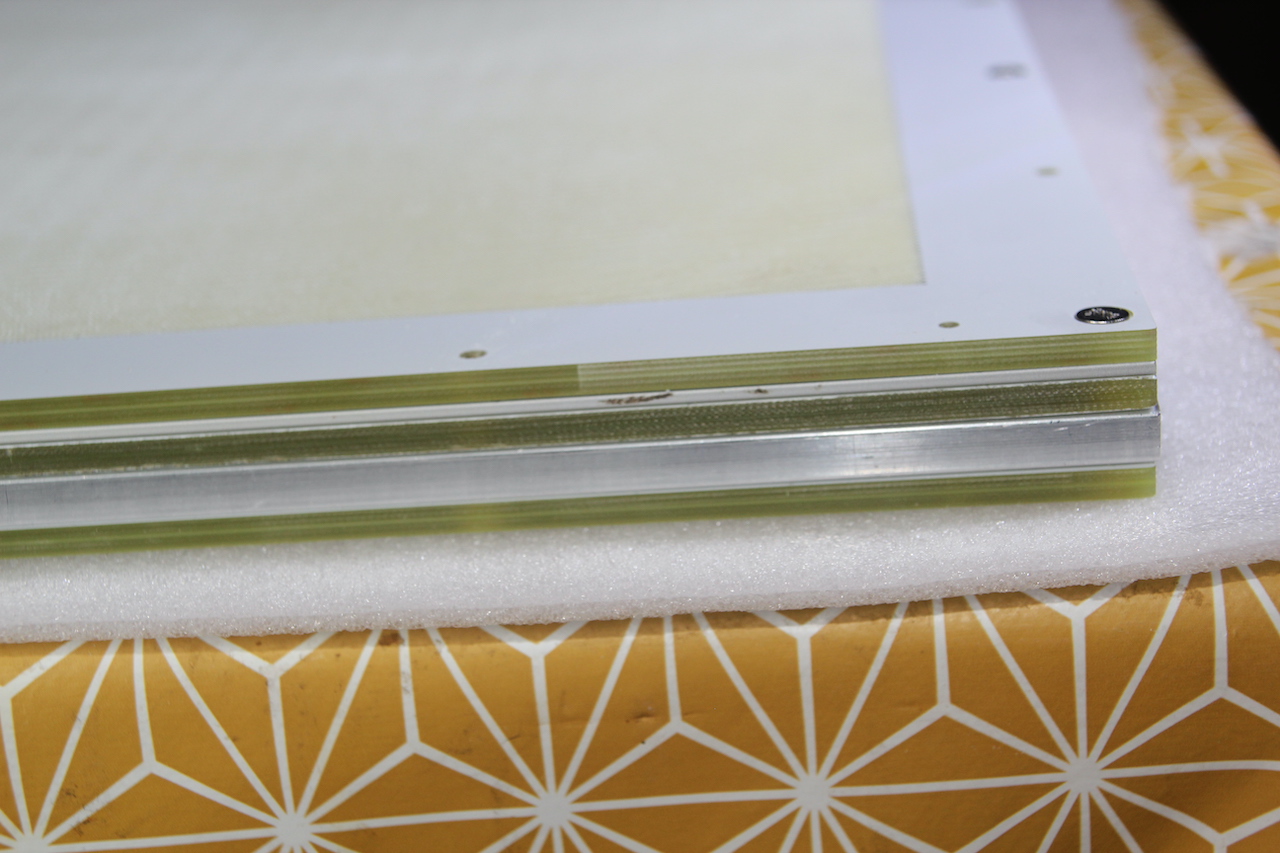

The screen was made using computer-assisted design, and Noyer subcontracted the actual manufacturing to factories equipped with computer-controlled drilling machines. These generally can’t drill deeper than 5 mm. As Noyer’s pins measured 30 mm, he had to make four separate plates, then overlay them and screw them together to create a sufficiently deep screen.

Foam was inserted between the first two plates to create friction when the pins are moved forward and backward. The idea is for the foam to prevent the pins from sliding forward and backward of their own accord, but for the resistance to be low enough that the pins can be manually moved without too much effort.

The pins were custom-made by another factory. Noyer treated them chemically to make them black (and protect them from rust).

Inserting the pins

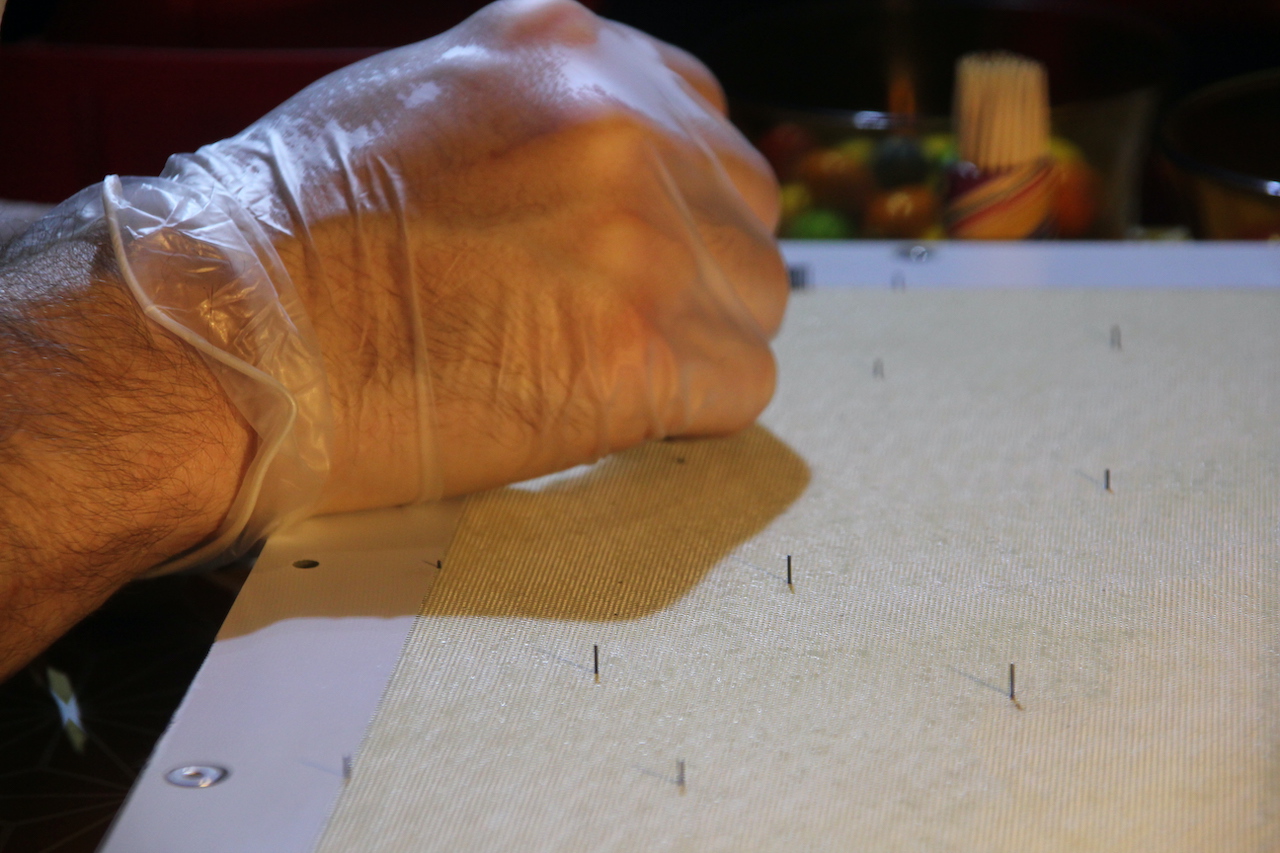

Then began the longest, most menial part of the process. The treated pins had to be wiped down and implanted in the screen, one by one. To make this stage more bearable, Noyer started hosting “pinned aperitifs”: evening get-togethers where friends would help him slot the pins in over a drink. “Contrary to what I thought,” he says, “the aperitifs were successful and people even came back and even invited friends, which allowed me to move faster.”

This method resulted in two smaller screens, The Cactus (26,000 pins) and The Spinae (100,000 pins). In 2019, Roy finished his short film Jim Zipper, which he made using The Spinae. Enthused by the experience, he suggested that La Bande Vidéo, where he had been selected for a residency, acquire a bigger screen. The center agreed, and commissioned Noyer to make L’Alpine for around USD$13,000.

For L’Alpine, Noyer more or less followed the process he had established with his first two screens. But this time, the aperitif parties were cut short by the fall 2020 lockdown in France. In all, Noyer says it took around 300 man-hours to insert the 201,600 pins, and he had to do half of that alone. He worked throughout November and December, posting progress photos on Facebook and even live-streaming himself at work. “I’ve been told that it relaxes people to watch me do this — much like a mandala,” he says.

Using the screen

At 201,600 pins, L’Alpine is considered full-sized, but is still smaller than the original Alexeieff/Parker models, which come in at 500,000–1,000,000. Its frame measures 53 x 40 cm (20.9 x 15.7 inches) — about as big as Noyer could make it while ensuring a filmmaker can easily work it on their own.

Although he used modern materials and technology to make the screen, it is functionally the same as the old models. “I challenge anyone who isn’t savvy to find a difference,” he says.

Even with the creation of L’Alpine, pinscreens are effectively off-limits to most animators, and will likely remain rare. Software has been developed to emulate their effect. But Roy believes it falls short of the real thing, as it fails to replicate the “element of randomness” that comes with manipulating a physical object — the little accidents and imperfections that give a pinscreen film its character.

Not only that, using a pinscreen is pleasurable in itself, as relaxing to do as it is to watch. As Roy puts it: “On a purely tactile level, using the pinscreen is a surprisingly satisfying and even soothing experience. The slight pressure needed to make the pins glide in and out gives a really pleasant sensation in the hands. When people start drawing on the pinscreen, even just for fun, they almost always get sucked in the experience and lose track of time.”

More details of La Bande Vidéo’s upcoming pinscreen residency will be announced in the fall. Watch Noyer’s demonstration of L’Alpine below:

Image at top: “Jim Zipper”