The Animation That Changed Me: Sébastien Laudenbach on ‘Gwen, The Book Of Sand’

We’re venturing deep into the French countryside for this edition of The Animation that Changed Me, a series in which leading artists discuss one work of animation that deeply influenced them.

Our guest is Sébastien Laudenbach, the director of around a dozen animated films. His sole feature, The Girl Without Hands (2016), won a prize at Annecy and a César nomination; Laudenbach animated the entire film alone in an improvisatory way. His short films include Vasco, Vibrato, and Regarder Oana, and he is currently co-directing a new feature, Chicken for Linda!, with Chiara Malta.

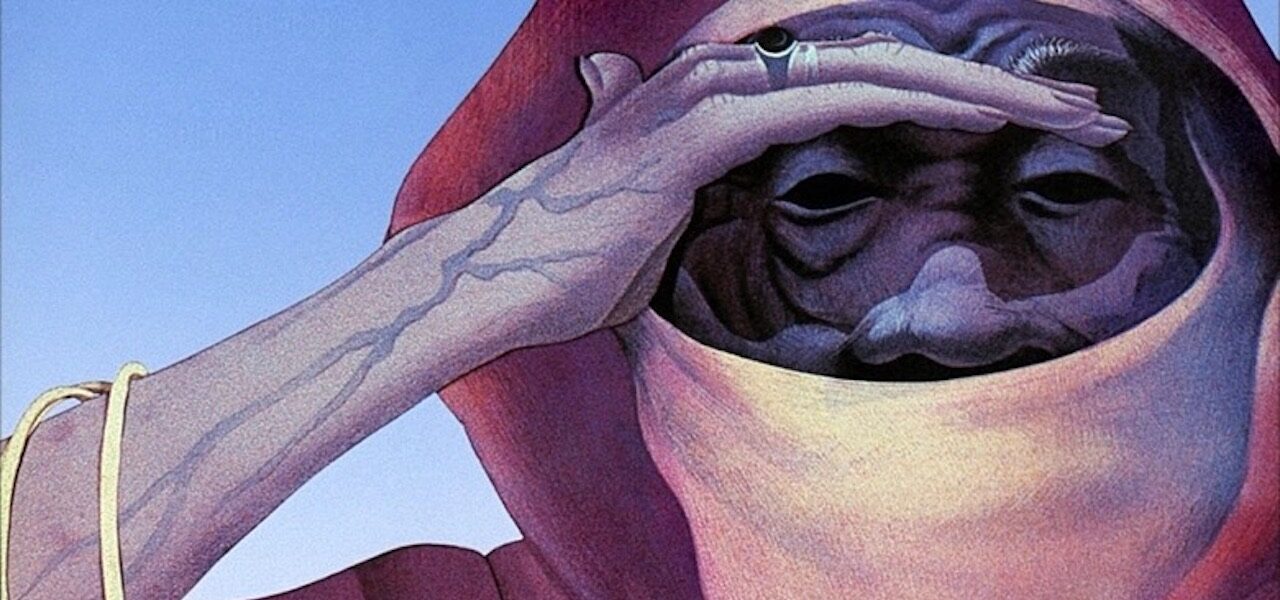

Laudenbach’s choice is Gwen, the Book of Sand (1985), the cult sci-fi feature by acclaimed writer-director Jean-François Laguionie. While Laguionie didn’t animate the film — his first feature — alone, he nevertheless worked independently with a small team. The story of its production captured Laudenbach’s imagination as much as the film itself, as he explains below.

We’ve also published this article in French, the language in which Laudenbach spoke to us — read it here.

Sébastien Laudenbach: I’ve never been particularly into animated films, even today. But when I was growing up, I read a lot of comics, and as a teenager I discovered the artists in Métal hurlant [a comics anthology adapted for the U.S. market as Heavy Metal]: Moebius, Bilal, Druillet, Caza …

A public channel in France had programmed René Laloux’s Gandahar, which had designs by Caza. So I was curious. On the same evening, they broadcast Gwen, the Book of Sand; I didn’t know who had made it.

Watching the two films, I ended up being pretty disappointed by Gandahar and very intrigued by Gwen. They both had their own identity, but whereas Gandahar seemed ultimately quite limited in its approach, Gwen took me to completely new places, on every level.

The design was based around faded tones — a far cry from the saturated hues of the animated films I knew; the story was mysterious, to say the least; the message was strong (even if I wasn’t sure I’d completely understood it at the time). Everything in this film was new to me.

Back then, I don’t think I fully grasped its anti-consumerist, anti-capitalist, libertarian dimension. [Yet] the scene where a mail-order catalogue is read like the Gospel made a particular impression on me. I remember thinking it was an extraordinary idea. It’s simple, effective, yet brilliantly staged. The tone (the sound!), the way the officiator speaks, the colors — the mood, basically, that solemn aspect … All that has stayed with me, even though I’ve hardly rewatched the film.

At the time, I had no thought of going into animation — I wanted to draw comics. I must have been 16 or 17. Two years later, I was getting started at art school, and chance led me to do animation. That’s when I reconnected with Gwen. Someone told me the story of La Fabrique, the very artisanal studio that had made the film under the direction of Jean-François Laguionie. A tiny team of people with ideals.

I’ve spent many a holiday in a farmhouse deep in the wild Ardèche countryside, and I liked this idea of a small studio in a village in the Cévennes [which overlaps with Ardèche]. I found it fascinating. I’ve had the opportunity to go to Saint-Laurent-le-Minier [where the studio is located], notably while Laguionie was working on Black Mor’s Island (2004). But I didn’t meet Jean-François then.

When I watched the film a second time, I knew the story of La Fabrique and this context must have guided the way I saw it. I don’t know whether the film has aged well: its rhythm is quite slow compared to contemporary productions — I’m thinking of the chase scenes in particular. But the film’s dynamic still works, in my opinion. Something in it builds, little by little, and ends up grabbing you. [Laguionie’s 2016 feature] Louise by the Shore has that same calm force, that gentle power, which I think is very close to how Laguionie is himself.

I think I preferred Gwen the second time, because I was judging its aesthetic aspects more sharply, having become a director in the interim. I was realizing how bold this film is, on every level.

I met Laguionie much later, at a round table to which we’d both been invited. We perceived a certain similarity in our approaches, and I think the near-solo adventure that was The Girl Without Hands spoke to him, brought him back to this era when he was making Gwen. He directed it aged 40–45, after eight or nine shorts, which was the case for me too. Even so, I didn’t think about Gwen when I was making The Girl Without Hands. It’s only afterwards that it struck me that they were kind of similar in approach.

Even if The Girl Without Hands is much more artisanal and experimental in its production than Gwen, I think both films share a spirit of freedom — in terms of their themes, of course, but also in the way they were made, in a departure from a standardized, established, immutable mode of production. These two films show us that there is another way (and they aren’t the only ones to do so, of course). In this regard, Gwen really made an impact on the history of world animation, and this is rarely acknowledged. Gwen is like its director: important and discreet.

I’m pretty certain that if Laguionie was my age, he could have made a film like The Girl Without Hands on his own, drawing on the freedom that digital tools afford when used in conjunction with traditional drawing. In this sense, we live in a relatively blessed time. It’s much easier nowadays to do animation on the cheap. Gwen is essentially made on cel (with some cut-out too), with backgrounds hand-painted on paper. It was all shot on a 35 mm rostrum camera.

Now, we can connect the marks we make on paper with a computer (to take the shot, to do the compositing); this results in a way of working that’s very different from back in the day. Nowadays, you can make films on the subway! That’s why, for a good ten years or so, we’ve been witnessing a boom in different types of animation all across the world. We’re in a new golden age …

.png)