The Animation That Changed Me: Nick Park on ‘Pogles’ Wood’

In a new installment of The Animation that Changed Me, a series in which leading artists discuss one work of animation that deeply influenced them, we’re taking a trip into the British countryside of yesteryear.

Our guest is stop-motion filmmaker Nick Park, whose works of plasticine-puppet animation at Aardman have earned him global renown. Park is the creator of Wallace & Gromit, Creature Comforts, and Shaun the Sheep; he also co-directed Chicken Run, the highest-grossing stop-motion film of all time, and directed the feature Early Man. His work has earned him countless honors, including four Oscars and five BAFTAs. He is a creative consultant on Netflix’s upcoming Chicken Run sequel.

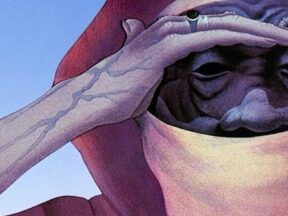

Park’s choice is Pogles’ Wood (1965–68), one of many acclaimed stop-motion series created by the British studio Smallfilms, which was led by Oliver Postgate (writer and animator) and Peter Firmin (puppetmaker and set designer). The show, whose first season was titled The Pogles, follows the whimsical adventures of a family of magical tree-dwelling beings …

Nick Park: I remember Pogles’ Wood from all through my childhood. [I first saw it when I was] probably about eight years old. It would be from the late sixties right through the till the mid-seventies. It was on a BBC show with a rather old-fashioned title: Watch with Mother. And it was kind of pre-school — before I think “pre-school” really existed — right up until ten years old. There was a slot every day around lunchtime that showed different animation from different studios. But the highlight for me was either Camberwick Green [created by Gordon Murray] or Pogles’ Wood.

I particularly liked Pogles’ Wood: it was enchanting and funny and magical, but also slightly weird. And that somehow hit a chord with me, even as a kid. There was a coziness to it and a magical quality, but it was also always a little bit offbeat and slightly weird, or even scary sometimes.

I started drawing cartoons around the age of ten — all through my childhood, really — but I wanted to be a Beano [comic] artist. And then I started taking an interest in animation around 11 or 12, started making my own [stop-motion] films. And it was really stuff like Pogles’ Wood that got me going. You can sort of detect how it’s done when you watch it: you’re aware it’s dolls moving around. The animation wasn’t slick or smooth or anything, but it had lots of character. I didn’t really refer to [the animation as a guide for my own work]. I just emulated it, but not directly.

It probably made animation accessible to me as an artist. I thought, “Oh, maybe I could do this.” Some forms of animation wouldn’t make you feel that way, especially today. You wouldn’t know what equipment you’d have to have — it’s all done on some kind of software or something. And even then, the Disney animation at the time was very elusive: how they achieved things was beyond you.

I do distinctly remember, when I was a child, because a lot of animation was quite limited — you know, there weren’t helicopter shots — it was all very limited to the set they built. But what it did was make you constantly wonder what was beyond it. It’s a funny effect. Whereas sometimes, when you’re given everything, there’s nothing left, because it’s all sort of dictated to you.

I didn’t really realize this at the time, but [Pogles’ Wood was partly] shot outdoors as well, so you could see the time-lapse effect as the sun moved in the sky. So the shadows are moving and the leaves are all twitching. That added a kind of surreal character to the whole thing. Whether that was done on purpose, I’m not sure. And then when you met the characters, they lived in a tree and there was a little old wooden door in the bottom of the tree. Now we’re so used to things like The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, but then it was something different.

One of the really enchanting things, which kind of drew me in as a child, was the voice of Oliver Postgate, because he would narrate the voices as well as animate, and he was an excellent storyteller. There’s something about his voice which was just mesmerizing, and I guess still today has a sort of nostalgic quality. I loved all of their work: it all had a slight quirkiness to it that didn’t feel at all designed for any market.

I met [Postgate and Firmin] a couple of times. Lovely people. They once came to Aardman: we invited them to talk about their work. Afterwards they opened a case and had all these Clangers in it, original Clangers [from the eponymous Smallfilms series]. They asked me if I wanted to hold one and I did. And I did actually drop a Clanger! It wasn’t damaged. They were much heavier than I thought — very knitted.

[Smallfilms’ work] rarely [comes up in conversations at work]. I think it used to. People who I’ve worked with in the past, like animator Steve Box, who animated the penguin in The Wrong Trousers and we co-directed Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit together. We were both big fans of Postgate and Firmin, and we used to watch it avidly and get inspired by it. I don’t really talk about it with many people these days, I guess, but the occasional person — when you’re going down some nostalgic conversation, it comes up. But they represented a big part of my childhood, really.

[I’ve rewatched Pogles’ Wood] many times: I’ve got tapes, dvds. I don’t sit down and watch them very often, but perhaps I should. I think what set [Smallfilms] apart was, there was a kind of — how would you say? — reality. [Gordon Murray’s] Trumpton is very stylized: simple figures that walk in a very precise way. I think the imagination was more free in Pogles’ Wood, and Oliver Postgate and Peter Firmin’s world. There was more texture, and it’s about real places like the woods, or the high street where Bagpuss lived. There was a magical quality in it: it’s more like little dolls that were coming to life.

Park’s answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.