The Animation That Changed Me: Marcel Jean on ‘Memories Of War’

For this week’s edition of The Animation That Changed Me, a series in which leading artists and industry figures discuss one work of animation that deeply influenced them, Marcel Jean joins us from Montreal.

Jean is the artistic director of Annecy International Animation Film Festival and executive director of the Cinémathèque québécoise. He has directed six films and produced many more, not least during his tenure as director of the French Animation Studio at the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), where he worked with renowned animators like Georges Schwizgebel and Regina Pessoa. He is also a prominent film historian and critic.

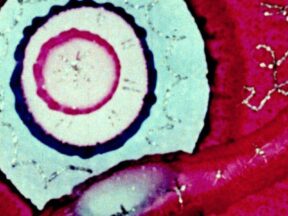

Jean’s choice is Memories of War (Souvenirs de guerre), Pierre Hébert’s timeless pacifist short, which combines scratching on film with cut-out animation. Hébert directed the film at the NFB in 1982. This titan of Québécois independent animation is the subject of a book by Jean, Pierre Hébert, l’homme animé (Pierre Hébert, The Animated Man).

We are also publishing Jean’s original commentary in French, which you can read here. Below is our translation. Over to Jean:

I first saw Memories of War in March 1983. At the time, I was studying cinema and writing for the university’s student paper as a critic. A highly anticipated feature by the Québécois filmmaker André Forcier, Au clair de la lune, was coming out in theaters. I saw it at a press screening and Memories of War was shown before it. So I wasn’t expecting to see it, as in Québec it’s very rare for a short to be screened in commercial venues before a feature.

At the time, I wasn’t really writing about animated films. I obviously knew the cartoons that were shown on tv in my childhood: primarily the films of Chuck Jones, Walter Lantz, Bob Clampett, Friz Freleng … I also knew Mr. Magoo, which was probably my favorite. I also knew a certain number of NFB films: Co Hoedeman’s The Sand Castle, Jacques Drouin’s Mindscape, Michael Mills’s Evolution, Frédéric Back’s Crac! … Strangely, I didn’t really know Disney. I think I’d only seen one feature: The Three Caballeros. And some shorts with Mickey and Donald.

My lack of interest in animated films stemmed from the fact that I considered them to be “pre-Godardian.” I believed that animation had resisted the advent of cinematic modernity and the questioning of modes of representation in cinema. I was totally fascinated by Bergman and Fellini, but above all by Resnais, Skolimowski, and Godard.

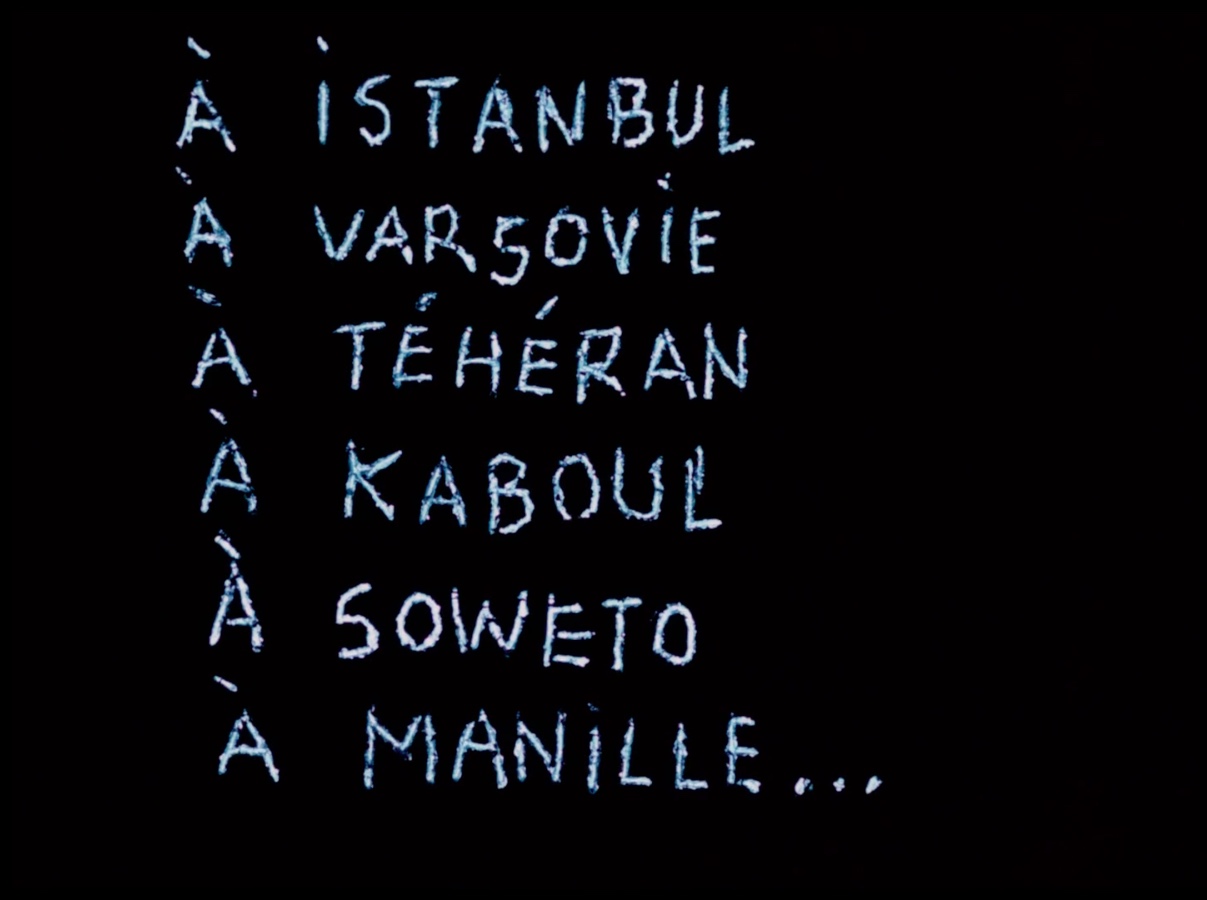

What immediately struck me in Memories of War was the application of Brecht’s ideas about historicization, distancing, and critical spectatorship. In this film, Hébert employs a series of techniques — analogy, breaks in the narrative thread, the use of popular music and onscreen text, etc — that create a sense of perspective through the alternation of two stories.

On the one hand, there’s the story of this blue-collar couple facing the consequences of an otherwise distant war. On the other, we have a story set in the Middle Ages about a page who is asked by his master to sacrifice himself for him during a raging famine … The film offers a timeless reflection on class, which serves as a framework for interpreting the present (namely, the situation around the war in Lebanon at the time).

To my eyes, this is a genuine work of theater, in the sense that the director harnesses all the means at his disposal to provoke a state of awareness in the spectator, who is treated as a thinking individual and not just as someone who can purge their passions through catharsis.

This is clearly a different matter, as the theoretical foundations aren’t the same, but soon afterward I discovered Jan Svankmajer through Dimensions of Dialogue. Then, a few years later, Breakfast on the Grass by Priit Pärn. The films of these auteurs are definitely what made me fall in love with animated films. I saw in them a genuine cinematic modernity.

I did military service in Canada, although I don’t personally have any “memories of war.” In a sense, the army had the same effect on me as playing a team sport (hockey). This is what it made me understand: to get a result, one needs to think about the collective and enter into a process that is greater than any individual by respecting the chain of command. That’s also how a film shoot works! More often than not, a film is a military undertaking.

I’ve rewatched Memories of War many times, first and foremost because I taught the history and aesthetics of animation at the University of Montreal for more than 20 years. I showed the film to my students during Operation Desert Storm in 1991, and again a few weeks after 9/11, etc. In a very interesting way, Memories of War always seems to draw its power from a sense of relevance. It’s a film that transcends the context in which it was created.

I met Pierre two or three years after seeing the film. At the time, he was starting to give performances in which he scratched on film. I was struck by the conceptual rigor of his work and his capacity for speaking about his creative process. As I was still very engaged in the university discourse on cinema at the time, I very much enjoyed talking with him.

This didn’t change the way I saw Memories of War, but it did make me want to devote myself to raising awareness of his films, as I thought he was undervalued by the animation community, which I was starting to discover. This is how I got the idea to write a book about Pierre and his work.