The Revolution in Interactive Storytelling Has Arrived, and Surprise, Google Is Behind It

Last week, Google’s Advanced Technology and Projects group released the second animated short, Buggy Night, in its Spotlight Stories, a series of interactive mobile-specific animated films available on Moto X phones. Like the first film in the series, Windy Day, which debuted last October, the new short relies on spatial awareness and the sensory inputs of a mobile device to create a distinctive storytelling experience.

Readers would be justified to express skepticism at the words ‘interactive’ and ‘animation’ being used in the same sentence. The concept has been touted often, yet rarely executed in a manner that suggests it could become a viable alternative to linear entertainment experiences. These shorts have finally proven, to me at least, that there is a promising future ahead for interactive animation and immersive worlds where multiple stories can unfold at the individual viewer’s pace, with no two viewing experiences alike. While it still requires some imagination to see where this could all go, and how it might eventually figure into our emerging augmented reality environment and mixed digital-physical world, the idea no longer seems as far-fetched and impractical as it once did.

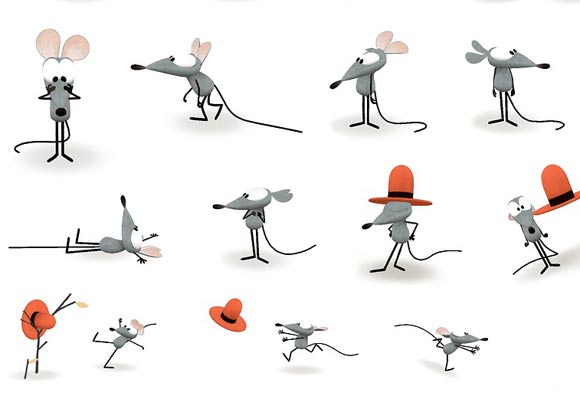

Before we imagine the possibilities, let’s look more closely at the pathbreaking animated shorts that stand before us today. The stories of both Windy Day and Buggy Night are simple but effective ideas designed to explore the interactive concept: in one, a mouse loses his hat on a windy day, and in the other, a group of bugs attempt to hide from a hungry frog. Since most readers of this site will not have a Moto X readily available to experience these shorts, simply imagine that you are standing in the middle of an animated scene. The action takes place all around you in a 360 degree space. Anywhere you turn your phone—left, right, up or down—could potentially reveal something happening. The film’s running time depends entirely on how often you, the viewer, chooses to move your camera—the more you move it, the longer it takes to finish the story. This video gives a sense of the physicality of the viewing experience:

The interactivity in these shorts not only feels natural, but adds immensely to the viewing experience. This success can partly be attributed to the amount of interactivity allowed to the audience. While control of the camera is ceded to the viewer, the overall narrative remains in the hands of filmmakers. It’s a careful balance between interactivity and linear storytelling that recognizes tried-and-true narrative structures can’t be reinvented—the only thing that changes is how we experience them. Over the years, we have moved from oral tradition to literary form, and finally, visual delivery systems like film and video. While each new mode of expression presents a distinct set of narrative possibilities, the underlying story form must remain intact, an idea heretofore not clearly acknowledged in interactive attempts.

Google’s entry into interactive storytelling and immersive animation began almost accidentally with their purchase of Motorola Mobility in 2012. Eager to explore the untapped potential of phones as an experiential device, they launched an open-ended research group called Advanced Technology and Projects—ATAP for short—to foster innovation and develop next-generation concepts. Spotlight Stories is one of the ideas that has emerged out of ATAP, alongside complementary technologies like Project Tango. (Google sold Motorola a month-and-a-half ago, but as an acknowledgement of ATAP’s importance, the group was not part of the sale and remains a part of Google.)

Google/Motorola also learned something that it took the computer animation industry decades to fully understand: if the creative potential of a technology is to be fully unleashed, creative people need to “challenge the technology,” as John Lasseter is fond of saying. Google brought on board a highly qualified team to push the limits of interactive storytelling. The first two films have been directed by Jan Pinkava (creator and co-director of Ratataouille) and veteran animator Mark Oftedal (who animated on Toy Story and A Bug’s Life among other films). Another Pixar vet, Doug Sweetland (Presto), supervised the animation, and notable children’s book author/illustrator Jon Klassen (This is Not My Hat) styled the look of the shorts. This core group worked in tandem with ATAP’s technical program lead, Baback Elmieh, and his team of technologists and scientists, to create the films. Continuing Google’s trend of working with A-list creative talents, another upcoming Spotlight short will be directed by Glen Keane.

The Spotlight Stories aren’t just exploring new ways of telling stories interactively, they are also pushing forward the technological development of mobile devices. Google touts in their promotion of Spotlight Stories that mobile graphics processors now rival the capabilities of video game consoles such as the PS3 and Xbox 360, a fact that will come as a surprise to the average smartphone user who is accustomed to the primitive worlds of Candy Crush and Angry Birds. This dormant computational power is finally being used, and in turn, developed further to meet the demands of the Spotlight Stories. Among the numerous technological highlights, the shorts contain the first-ever real-time subdivision surfaces on a mobile device using Pixar’s open graphics standard, OpenSubdiv. Not so coincidentally, Windy Day’s director Jan Pinkava also directed the Oscar-winning Geri’s Game (1997), which was the first Pixar production to use subdivision.

Stay tuned to Cartoon Brew, where next week we will dig more deeply into the creative and technological challenges of interactive storytelling in an interview with Jan Pinkava.

(Disclosure: Google provided Cartoon Brew with Moto X phones to view the Spotlight Stories. The phones have been used for the sole purpose of viewing the shorts.)