In The Dome: Mexican Filmmaker Jesús Pérez Irigoyen Discusses His Adventures In Immersive VR And Dome Animation

Born in Mexico City to a family of self-taught entrepreneurs, Jesús Pérez Irigoyen gravitated toward visual arts and graphic design, before branching out into broadcast television and founding his own Dessignare Studio in the municipality of Tlalnepantla de Baz. “In my family,” recalls Pérez Irigoyen, “art and design weren’t things that your family would push you to pursue. When I was growing up, there were no animation schools in Mexico. After I graduated as a graphic designer, I joined one of Mexico’s biggest broadcast channels, Televisa.”

While working at the broadcast station’s educational wing, Fundación Televisa, Pérez Irigoyen collaborated on a series of animated short films. He showcased the work on his Dessignare blog, which he then developed into a production entity. This led to assignments directing animation, branded content, and immersive video-mapping projections. Recent work has included institutions for social programs, education, and the arts, including the Cultural Center of Spain, the National Water Commission of Mexico, the rock band Human Spiral, and exhibits for young science buffs at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Munich.

Science venues led Dessignare to explore unconventional screen formats for animation in planetarium venues and virtual reality. “I have a personal interest in technology,” says Pérez Irigoyen. “I divided my company into two groups – Dessignare Studio and Dessignare Media, dedicated to my journalism in the industry. While attending SIGGRAPH, I got inspired by what was coming in VR, and I started to introduce that into my work, building content for our portfolio. And at Annecy, the Google Spotlight Stories inspired me to move into immersive media.”

Pérez Irigoyen’s two children also provided feedback as representatives of Generation Alpha whose imaginations have formed with immersive realities at their fingertips. “Planetarium shows are typically formatted from 20 to 25 minutes,” noted Pérez Irigoyen. “When I attended those shows with my family, they were educational, but not entertaining and they [lost] the attention spans of children. I decided I wanted to try to create [programming] that could be fun, but also leave a message.”

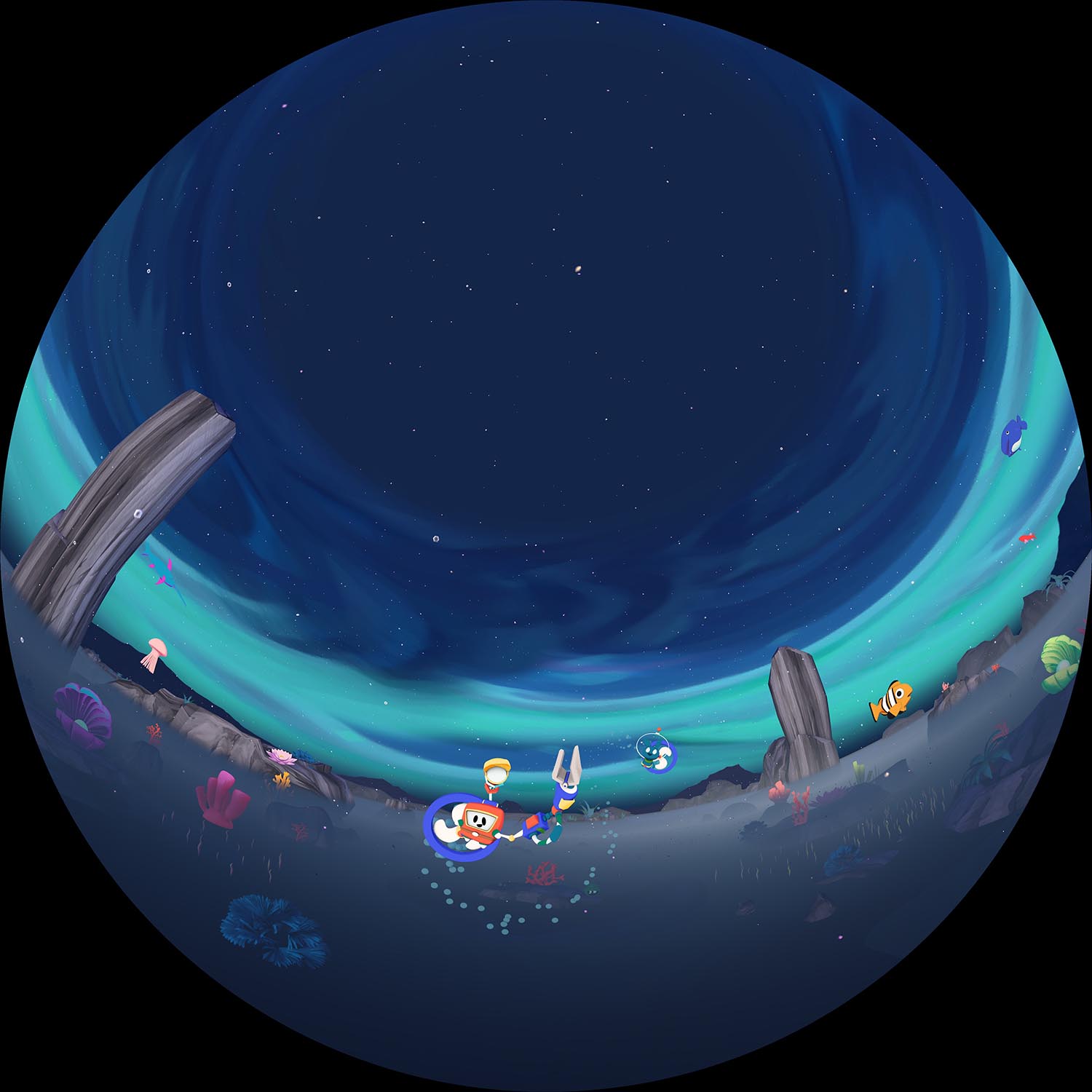

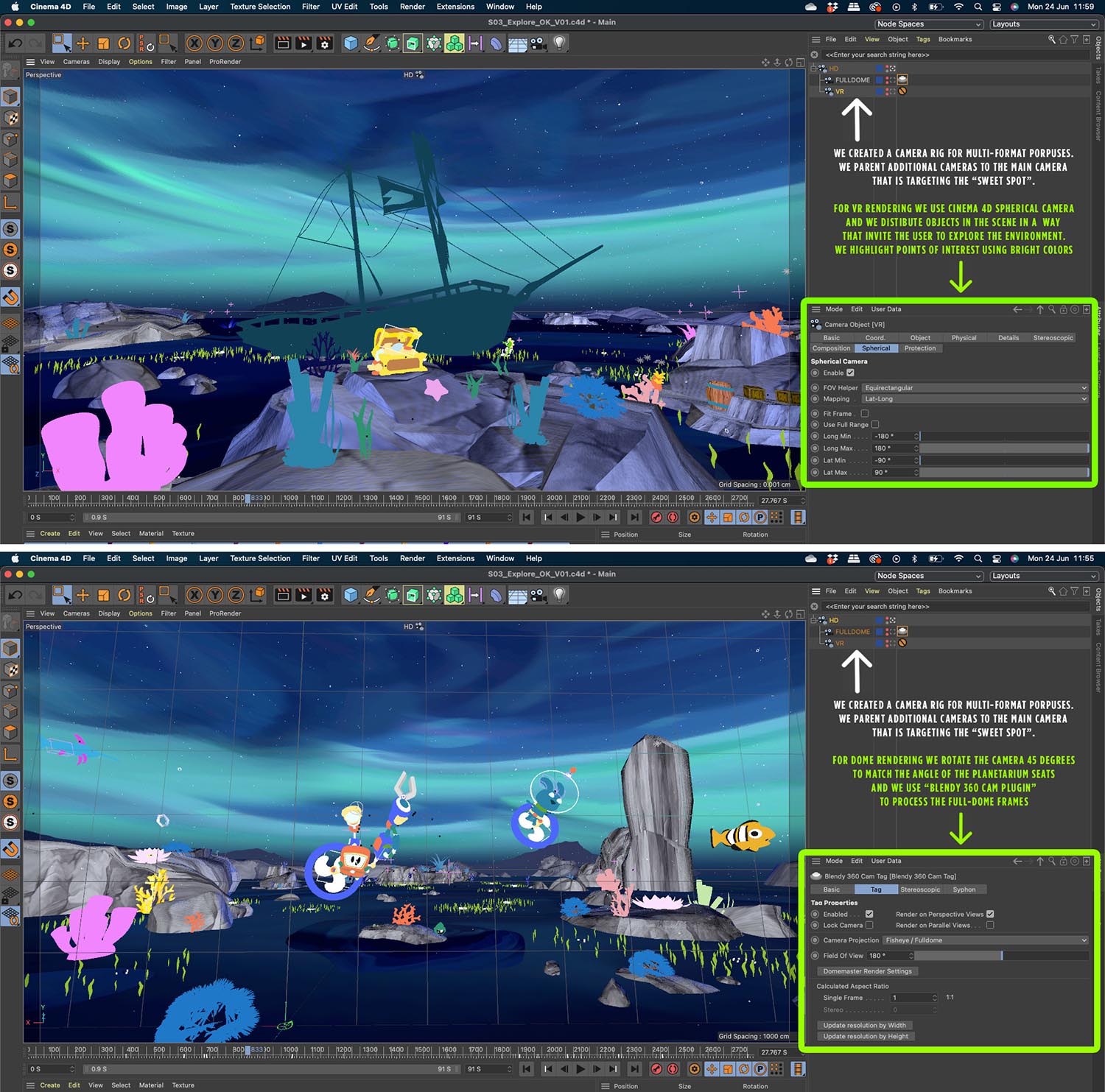

Dessignare Studio’s Cosmonaute 360, screened at ESO’s Supernova Planetarium, involved a stylized astronaut character who inhabits outer space environments in snow-globe-like projections for a half-dome screen, and an additional VR exhibit where participants don headsets to navigate alien underwater realms. Dessignare developed production pipelines for the new media formats working with plug-ins from a Brazilian software developer combined with off-the-shelf hardware of After Effects and Maxon Cinema 4D, allowing animators to create 3d animation unrestricted by the proscenium of a traditional film frame.

“Creating a world and storytelling in immersive reality can double the work for digital creation,” Pérez Irigoyen said. “We have two approaches for working in a hemisphere dome or VR. We’ve done shows in both formats, and both have their challenges. Something that I have learned in talking with other creators in immersive media is to think of your story – why are you using this format, and how does that benefit your story? It makes sense to use this for planetarium venues, looking to the sky and the stars. But it is important to understand ‘spacial’ qualities, how does the audience respond to different compositions?”

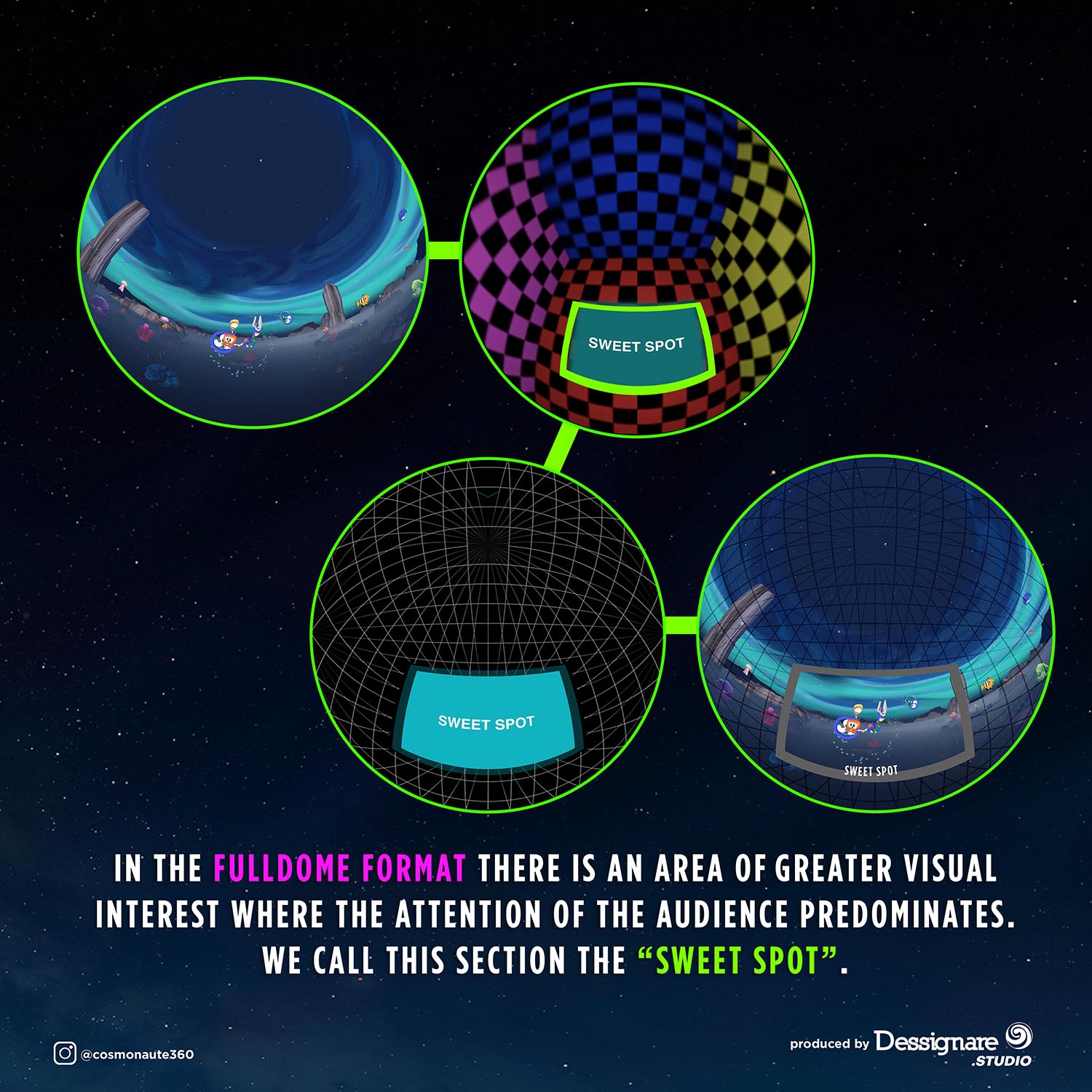

Both VR and hemispherical formats require special lenses and wide fields of view, where animators focus compositions on ‘sweet spots’ within the broader perspective. “You direct people’s attention to that sweet spot,” notes Pérez Irigoyen. “To do that, we use composition, color, scale, and even sound. People may get curious and while they are looking around [the screen], you don’t want them to miss a story point. You guide them, but you must be aware that you’re stimulating their curiosity. You must do tests, otherwise people may get dizzy, or they may not catch the message you are trying to show. It is 3D animation, but our approach is more like developing a video game and, depending on the level of interactivity, we use more technologies.”

To help viewers navigate VR spaces, Dessignare created a soft-toy gadget, resembling a brightly-colored NASA-style camera, for viewers to wield as a pointer in 3d space. Gripping the imaginary camera, with their cell phone Velcroed to the plushy prop, viewers interact in real-time within the immersive animated universe.

Pérez Irigoyen is excited to explore further adaptations of audience interaction with 3d animation. “The concept of our new film is you become a filmmaker, and you take pictures and capture video. That’s what we’re conceptualizing now. It’s nice to see how people become playful as we add more sensorial technology. You don’t need a lot of high-tech [gear] to get people to feel something, creating animation more as a performance. We did another collaboration in Taiwan, where we created a show that accompanied a balancing performance, with dancers trying to touch the stars. It becomes more theatrical, the more we use other levels of interactivity.”

The recent 2024 Dome Fest West Immersive Cinema Film Festival in Boulder, Colorado, showcased creative applications for spherical cinema and animation, reflecting a recent rise in popularity– from small-scale experimental operations to high-end special venues such as the 18K projections of the Las Vegas Sphere. Pérez Irigoyen, who participated in the event, explained his experience there and the potential that this space holds filmmakers:

It’s been six years since I started getting to know this industry. I wasn’t wrong. People want to bring more stories to these places. And it’s not going to be exclusive. There’s going to be a focus on educational purposes, but it’s opening up to more experiences. For example, there is a big trend in electronica music, giving people a way to experience visuals on the music side. But they are pushing for more family participation in different kinds of film experiences. At Dome Fest, they showcased many different projects – people traveling through Asia, visiting temples with 360-video, giving people a way to experience those adventures on a dome. They had exhibits where people used their phones to play games, like Space Invaders, with other people in a dome. Another person presented architectural tours and, using an Xbox controller, the host could walk around the room in the dome. As more of this technology becomes accessible, we want to try to create real-time dome experiences. We want to explore that interactivity, letting people take control of the film. It’s something new.

.png)