‘Son Of The White Mare’: The Journey Of The Cult Classic’s 4K Restoration (Interview)

After going decades without an American distributor — then spending a few extra months in pandemic limbo — one of the great wonders of European cult animation is finally hitting our screens.

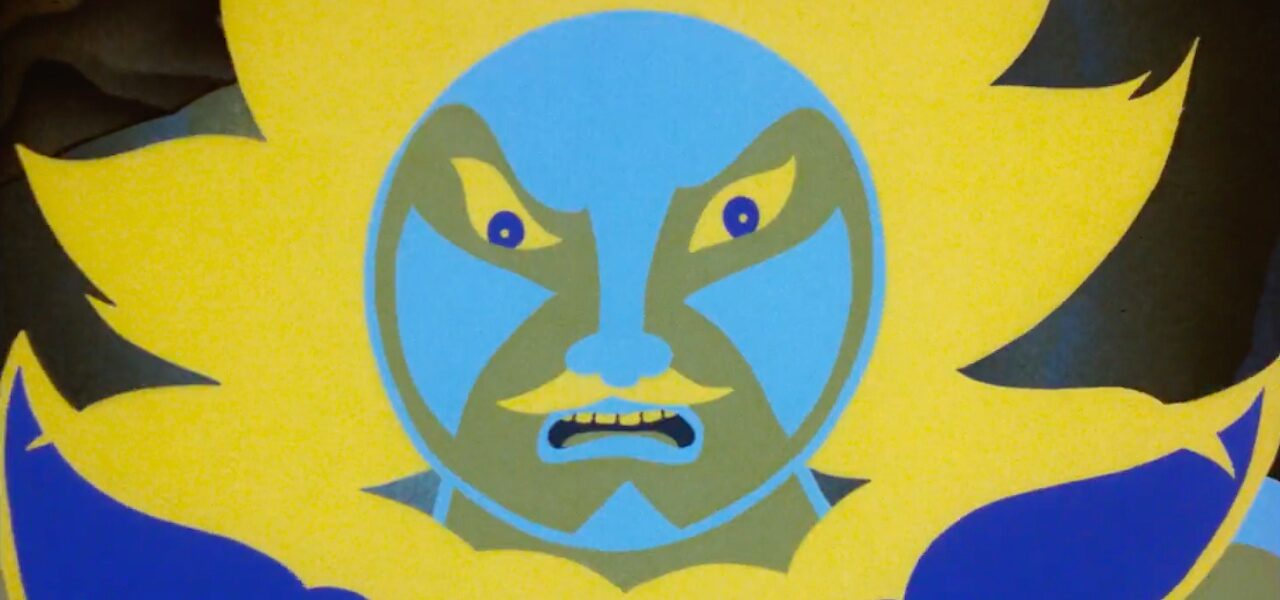

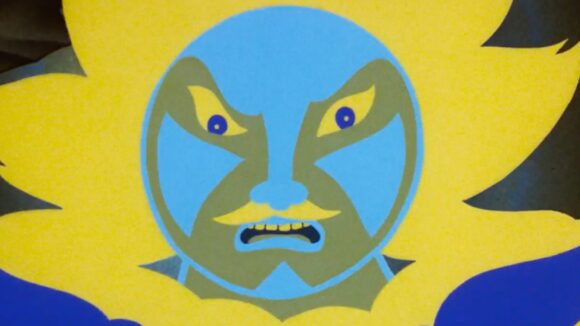

Son of the White Mare (Fehérlófia, 1981), the heady masterpiece of prolific Hungarian filmmaker Marcell Jankovics, is released on video on demand today. Not only that, it arrives in a new 4k restoration that makes its psychedelic images really pop.

Jankovics has created over 200 animated works (among them series, shorts, and commercials), written and illustrated over a dozen books on mythology, and worked a short stint at Disney. His feature Son of the White Mare takes its cues from Hungarian myths, telling a tale of kings, dragons, and heroic derring-do. On the whole, the story plays second fiddle to the extraordinary design, an explosion of vivid colors and shifting shapes that have had viewers suspecting the influence of drugs.

The restoration was carried out by L.A.’s Arbelos Films, a film restoration and distribution firm that works across live action and animation, and the Hungarian National Film Institute – Film Archive. Following a festival run, the restored film was due to be released in theaters in March.

The virus interrupted that plan. As the pandemic unfolded, Arbelos took note of the “virtual cinema” initiative spearheaded by other distributors, whereby closed arthouse cinemas promote indie streaming releases in return for a cut of the revenue. Son of the White Mare will be released in this format tomorrow, although theatrical screenings are on the cards in the future (and overseas).

The disruption is a shame but not a game-changer. As David Marriott, Arbelos’s co-CEO and co-founder, tells Cartoon Brew, “Luckily the restoration looks stunning on big and small screens alike.” Below, Marriott and fellow co-founder Craig Rogers tell us how the restoration came about, and discuss the challenges posed by the film — and animation in general…

Cartoon Brew: How did this restoration project come about? How long did it take in total?

David Marriott: We’ve made a concerted effort to restore and champion lost masterpieces of path-breaking animation. It’s a genre we feel really strongly about and Son of the White Mare is really the perfect case in point: it’s a flat-out masterpiece that wasn’t currently available in a high-quality version and had never been officially released in the U.S.

With that in mind, we reached out to the Hungarian National Film Institute – Film Archive in Budapest, who controlled the rights and held the original film materials, and started a two-year conversation around how we could jointly restore the film under the supervision of the great Marcell Jankovics.

In what condition was the negative?

Craig Rogers: Overall the negative was in solid condition. There were no major flaws, tears, etc. The bulk of the issues were small surface scratches and dirt on the negative, as well as a tremendous amount of photographed-in dust and dirt.

Could you give some insight into how your team approaches the process of restoration? How do you know how the film “should” look?

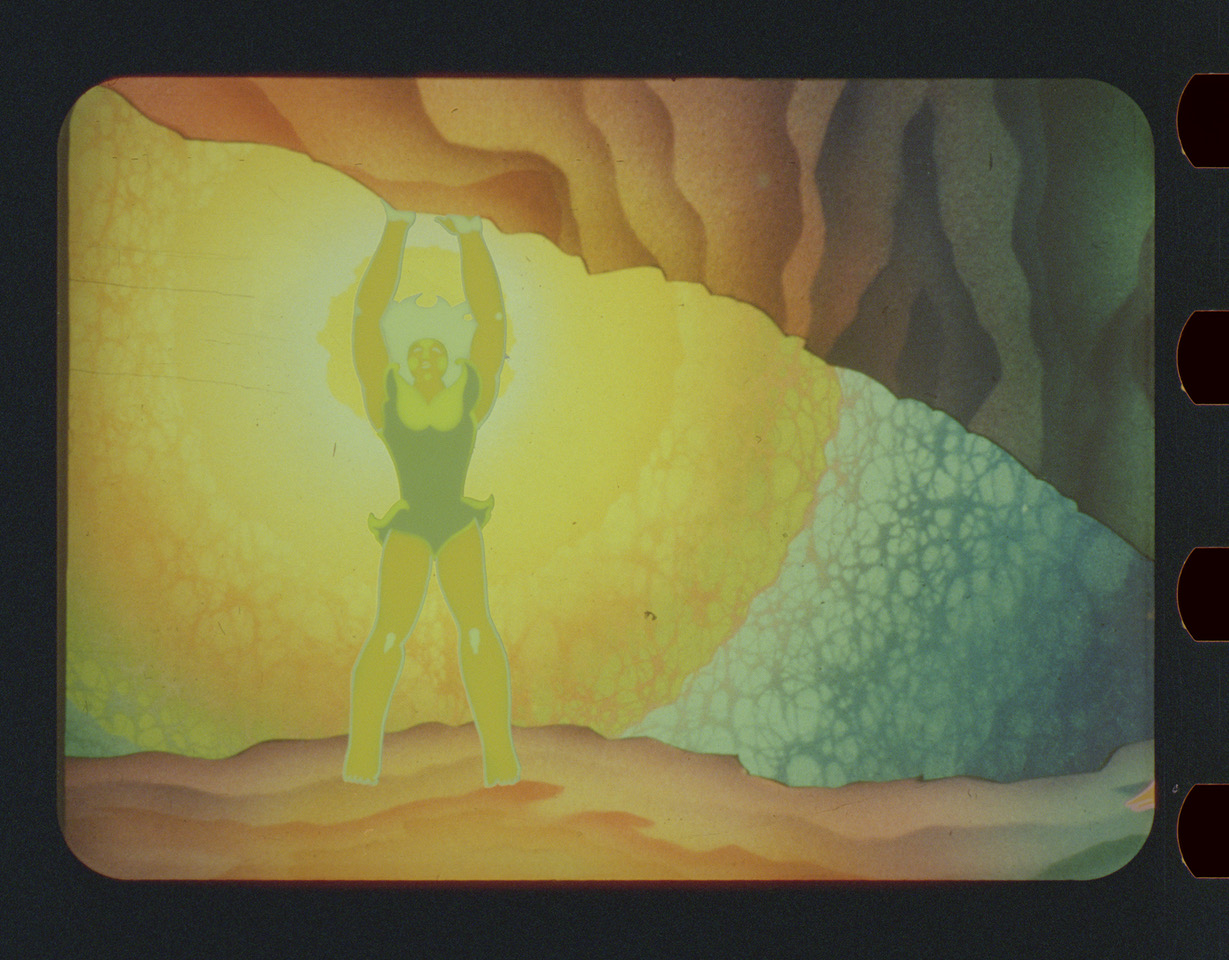

Rogers: It really varies from project to project. It depends on what materials are available to view and who from the production is available and/or willing to weigh in. From a technical perspective, what a film “should” look like is dictated by the film elements themselves. Film negative looks different than an interpositive (IP), internegative (IN), or print would. You need to work with what you have available.

The trickier part, and what I think you’re getting at, is the aesthetic, which is where color grading (correction) comes into play. It’s a huge part of the restoration process. The goal when completing a restoration is always to get the earliest source element possible, which is the original camera negative. It will provide the sharpest, highest-resolution image.

However, in the production of feature films, all of the color-grading choices were made at the lab and are baked into the IP, IN, and prints. Those color choices do not exist in the original negative. That’s why it’s imperative that you work with someone from the production, preferably the director and/or cinematographer, as well as look at previous home video releases — or, better yet, quality film prints.

If possible, you don’t want to rely solely on one or the other — a filmmaker’s memories of what something looked like can change and previous video releases may be incorrect. With Son of the White Mare we were able to do both, with Marcell Jankovics sitting in on the color-grading sessions and approving everything.

How common is it for the director to be involved (when alive)?

Rogers: The level of the director’s involvement varies from project to project. It’s really up to them. We always reach out and offer for them to be involved. Sometimes it’ll be as little as a sign-off on the final project; other times the director will be more hands-on, as Mr. Jankovics was with this restoration.

How did your partnership with the Hungarian National Film Institute work in practice — were you in constant contact, or were the different parts of the process quite self-contained?

Rogers: Their film lab in Budapest scanned the original negative. Those files were sent to us and we handled the cleanup/restoration work here in L.A. That was sent to Hungary for feedback; we then addressed any and all notes they provided. The final restored images were then color-graded at the lab in Budapest with the director. All of the audio restoration was handled by the lab in Budapest as well. The final picture and audio master was then approved by us here in L.A., where we create the DCP and Blu-ray for theatrical and home video release.

Did this film pose any particular challenges for you?

Rogers: Having to work from the ungraded files can be challenging, as some more subtle problems can be hidden until the final color grade has been applied. It just meant that an additional round of clean-up work was required after receiving the final color-corrected files.

On the whole, do you approach animation and live-action restorations differently?

Rogers: It is a very different process, actually. Traditional animation is a very hand-made process. It’s particularly noticeable when viewing it frame-by-frame: you can literally see the work that went into making the images. You don’t want to lose that with a digital restoration, or the little imperfections that are an integral part of an animated film. These older films were also just that: film. The nuances of film should remain. My goal is to make the images look beautiful and clean, not sanitized. Finding the right balance is the key.

One of the most significant differences is the fact that animation is double-printed. That is, each frame is photographed twice. That becomes an issue when the background plates and cels are not perfectly clean when photographed. It means you not only need to clean up all the issues with the negative (dust, dirt, scratches, etc), but there are also bits of dirt photographed in that repeat.

Restoration software is designed to flag dirt only if it’s there for a single frame. If the same spot repeats, the software ignores it. We’ve developed a workflow that helps address the issue, but it still requires extra time-intensive labor.

Does the process of restoration change the way you feel about the film?

Rogers: Absolutely. I spend a long time with these films. I get to see the craftsmanship that goes into them. I appreciate them on a level that a casual one-time viewer does not. There’s a special place in my heart for each film I’ve restored.

(“Son of the White Mare” can be rented on Vimeo on Demand in North America.)