Ollie’s Odyssey: A Behind-The-Scenes Look At The Twelve-Year Journey Of Netflix’s ‘Lost Ollie’ (Exclusive)

Netflix’s latest limited event series Lost Ollie hits the streaming platform worldwide today. But most viewers who fall for the floppy-eared protagonist and his hero’s journey will never know just how much work went into making the show happen, and how many people contributed along the way.

Lost Ollie is an epic adventure story about a lost toy who faces down tremendous challenges to reunite with the boy who lost him. The four-part limited series was inspired by the book Ollie’s Odyssey by renowned author and illustrator William Joyce, whose involvement with the show stretches back more than a decade.

As a project, Lost Ollie was hanging around the Netflix offices for several years before 21 Laps was brought in to produce, Shannon Tindle to adapt the book and executive produce, Peter Ramsey to direct and executive produce, and ILM to handle vfx and animation.

But the real Lost Ollie origin story goes back much further, to a post-Katrina Shreveport, Louisiana, where Lampton Enochs, recently relocated from New Orleans, teamed with Joyce and Brandon Oldenburg to launch the Oscar-winning production house Moonbot Studios in 2009.

Here is the story of how it all came to be. . .

Ollie’s Origins

In its few years of operation, Moonbot proved a prolific entity, producing several short films, interactive apps, and transmedia productions, including 2012 Oscar-winning short The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore. The goal, however, was always to get into original IP.

To that end, the story of Ollie was one that developed slowly over time at Moonbot, taking on several iterations across the years.

The original idea: “We can all universally connect to having that one favorite thing that we always lost track of, but it was so important to us,” Oldenburg explained to Cartoon Brew. “At that time, my girls were very young and my youngest had a blanket that, during development, we would talk a lot about and how, as parents, we’d turn over every leaf and rock to find it if it got lost.”

Between 2010-2015, several writers were brought in to contribute to the developing Ollie story, including a straight-out-of-college Jake Hart, son of screenwriter James V Hart; Heather Henson, ghost writer of Ollie’s Odyssey; and Angie Sun, now a producer at Glen Keane Productions.

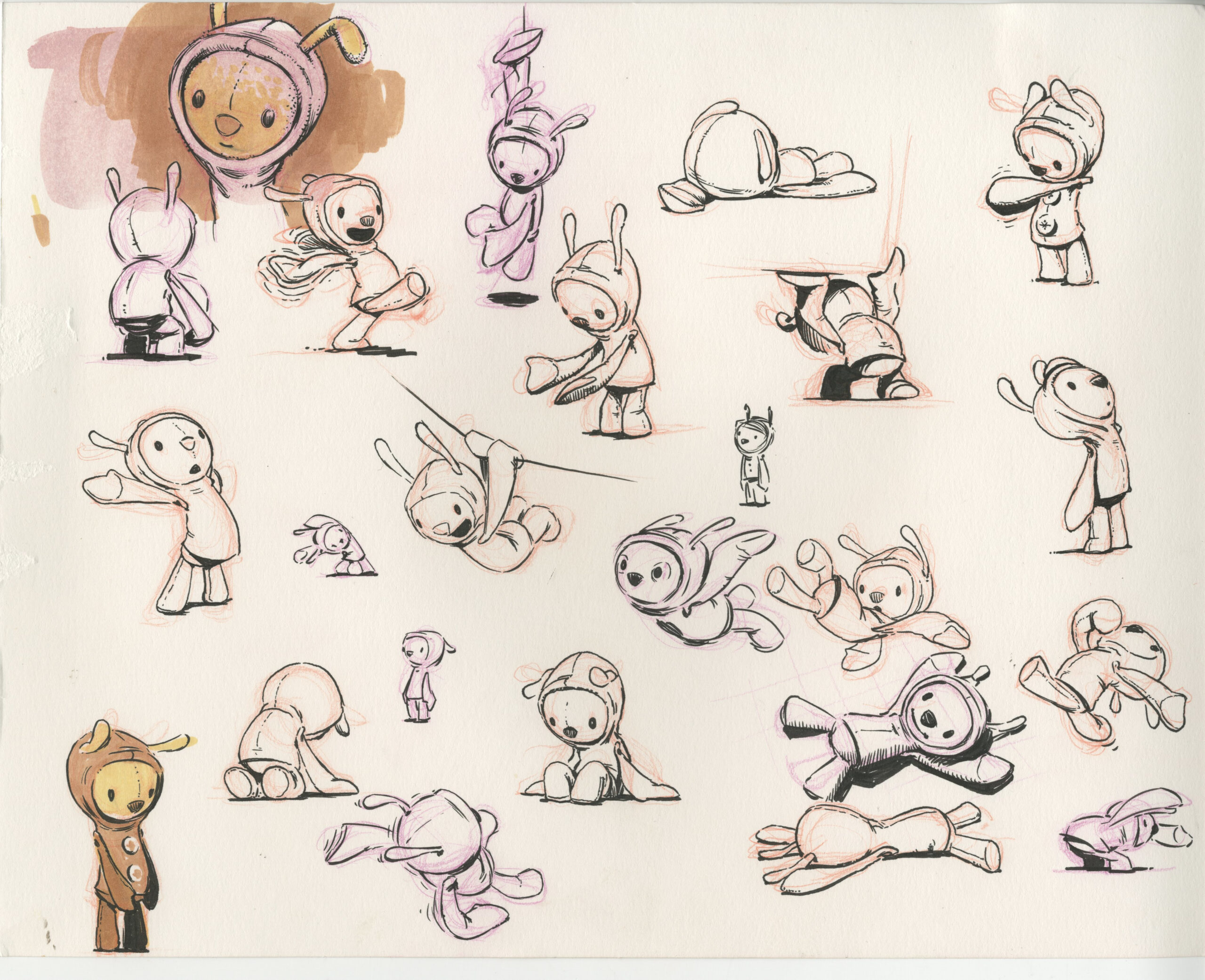

Artists who worked on the earliest versions of Lost Ollie included character artists Joe Bluhm and storyboarder Stanley Moore, the latter of whom would go on to co-found Kuku Studios, with Oldenburg’s own sketches and drawings acting as a guide for the project’s aesthetic. No one format was nailed down at that early stage, especially since Moonbot was experimenting in several transmedia spaces, and nothing was off the table.

One such iteration, which will look familiar to anyone who has seen the Netflix version, was a traditional live-action-3d hybrid film or series. Oldenburg and Enochs shared a very early animatic and an animation test for a screen-based version of Lost Ollie with Cartoon Brew, which can be seen below.

Interactive Ollie

While working on that early version of Ollie, the Moonbot team was visited by Arthur Mintz, who runs the puppeteering Swaybox Studios. Together, the companies shifted away from a more traditional screen narrative for the Lost Ollie IP and began developing the story as an immersive, theater experience which played with scale and perception, and even a bit of augmented reality.

In that early version, audiences would be invited into a large soundstage and seated beneath a supersized pillow and sheet fort. After being introduced to the story in a room where everything was to scale with the audience, the blanket fort was to be lifted up to the ceiling of the soundstage, revealing a new interactive environment in which audience members would now be the size of Ollie and the other toys.

The interactive plan was just one of several for Ollie however, and Oldenburg remembers that while developing the story, Moonbot went “through the early development stages that you would normally do at an animation studio, trying to find the voice of a character and the voice of a show. We were drawing a lot, storyboarding a lot. We were writing and eventually found our way to what became the book, but we had already developed the story and gone through multiple iterations.”

Netflix Shift

After Louisiana’s tax credits dried up, Moonbot was faced with shuttering or accepting an acquisition offer. However, accepting the offer would have meant handing over the full Lost Ollie IP, which the team considered to be their studio’s magnum opus and, therefore, a deal breaker. Instead, Oldenburg reformatted the narrative from its previous iterations and he and Sun pitched the story to Ted Biaselli at Netflix in 2015.

“Before they had their big fancy office in Hollywood, you would walk into the lobby and just feel the energy they had,” Oldenburg recalled from his early visits to L.A. “They didn’t have enough conference rooms or coffee tables for all the meetings they were taking, and while you were sitting there waiting you were surrounded by some of the most interesting, exciting storytellers working at that time.”

Biaselli was enamored and immediately agreed to purchase Lost Ollie from the duo, then started pitching major talent (Genndy Tartakovsky to showrun, Joan Considine Johnson to write) in hopes of getting production underway quickly. To this day, everyone who worked on the Netflix version of Lost Ollie credits Biaselli as the champion who kept the project going at the company.

“He just got it,” Enochs explained. “He got it right away and loved it so much, and he was such a huge cheerleader for us, and sometimes you need that. He never stopped trying to find a home for Ollie.”

That cheerleading was necessary, as it was several years after the initial pitch that Tindle and Ramsey were brought on board to work on what would become the Netflix version of Lost Ollie.

Ollie Goes to Netflix

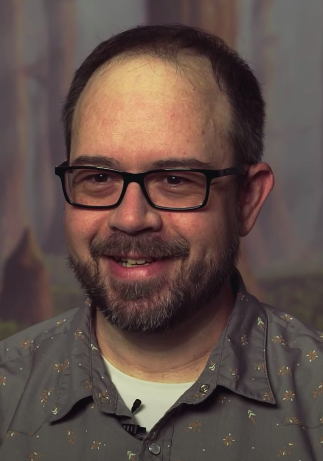

“In the fall of 2018 I was traveling to Stuttgart for the festival there and I read the book on the plane,” Tindle told Cartoon Brew of his first exposure to the IP. “I didn’t even know that Brandon and Lampton were executive producers until I came back to the States a week later.”

Shortly after returning to L.A., Tindle met with Biaselli and Carolina Garcia from Netflix, as well as Josh Barry and Emily Morris from 21 Laps, producers of Stranger Things, the Night at the Museum franchise, and many other films and series.

By this time, Tindle was already a fan of the book. “The things I connected most with were that this story dealt with loss and how all of us process loss, and that it was set in the south, where I come from,” he said. He played up those aspects of the story in his pitch, which eventually paid off as he was selected to head the show.

It wasn’t until after the pitch had been greenlit by Netflix that Tindle found out that Ollie had first been developed at Moonbot. When he did find out, he was thrilled, as he’d known many from the Moonbot team for years and enjoyed their work.

“I was like, ok great, all the better. Let’s hear about your process and what the journey so far has been like for you,” Tindle recalled. And, while the version of Lost Ollie on Netflix is very much a Tindle creation, some of those initial sparks from Moonbot still find their way to the screen.

Thrown For a Loop

Initially, Lost Ollie was commissioned for eight half-hour episodes, and that’s how Tindle and his team wrote their early drafts. Only later was the decision made to switch to four 45-minute episodes, throwing the show’s creator and his writers’ room for a loop.

“To be honest, that was a bit of a throw because pacing is everything,” he admitted. “I’d pitched and started writing the series as eight episodes, and we didn’t have a lot of time to restructure it. Thankfully, we did get the benefit of longer episodes, so it wasn’t as if the show got cut in half.”

The decision to drop from eight to four episodes also had a major impact on how the series was directed. Originally, Tindle and Ramsey were meant to split directing duties, four episodes each. But when the pandemic began and restrictions were imposed on film and tv productions, Tindle would have needed to put his show Ultraman on hiatus to direct live-action scenes for Lost Ollie.

“I wasn’t willing to do that. I didn’t want to leave that team high and dry, so I asked Peter, ‘Can you direct them all?’ Peter and I are very tight, and I knew he could do it on his own, and he really just stepped everything up and knocked it out of the park,” said Tindle.

Boarding and Design

Describing his approach to writing and storyboarding, Tindle explained that, “I don’t write any differently for live action than I do for animation. The process is the same in either case. I’m always doing a mix on the page though, writing and sketching moments. I even did that in the writers’ room where I’d draw a quick sketch and we’d all chase that idea.”

Although much of the series is animated, Tindle explains that he, Ramsey, and the crew didn’t storyboard Lost Ollie like they would an animated production.

“We didn’t cut storyboard animatics together,” he explained. “There was some boarding ahead of time during prep so Peter could have his setups, but it was not the way it is in animation where you board and cut and finesse. But I liked it that way because a lot of times in animation people can’t improvise or imagine as much.”

While that lack of explicit direction could be stressful at times, Tindle argues that the decision to limit storyboarding forced the crew to work on their toes and be adaptable, and that they would often find things in frame that they would never have thought of during writing or storyboarding.

For Tindle, the hardest part, or at least the most important part, of designing and animating Lost Ollie was ensuring that the animated characters could match the performances of their live-action counterparts.

“Visual effects and standard character animation in an animated project go hand in hand. They face the same difficulty of, ‘Does that character feel believable?’” he explained. “We had amazing live-action performances, and if the animated characters’ performances aren’t believable for even a moment, the whole show fails.”

Tindle credits the artists at ILM for ensuring that his character designs were faithfully brought to life, and delivered believable performances in every frame. He credits everyone who worked on the show, from its earliest days at Moonbot through to today’s release, for what audiences will be able to stream starting today.