Franck Dion On The Journey Behind Making ‘The Head Vanishes’

We asked filmmaker Franck Dion to share how a story passed down by his mother led to his creating the National Film Board of Canada/Papy 3D/ARTE France project The Head Vanishes, a nine-minute short about Jacqueline, who isn’t quite in her right mind anymore but is determined to ride the train to the seaside. Jacqueline is followed by a woman claiming to be her daughter, and her trip takes some unexpected, phantasmagorical turns.

Here, Dion talks about the making of this poetic film that brings us inside the faltering, fragile mind of a woman living with dementia, and how he used his skills as an actor, theater set designer, and illustrator to complete the project.

A family affair

My great-grandmother, who died when I was 11, had dementia for about seven years. I was very close with her; she helped raise me. She was extremely intelligent and refined, so to see someone deteriorate like she did was very painful emotionally. The idea for The Head Vanishes came from an anecdote that my mother Nicole told me. My great-grandmother once asked her to fetch her head from under the sink, because she was convinced it had rolled under there. That image stayed with me, and I wanted to use it in a literal sense, because animation lets you do that kind of thing fairly easily.

A story that begged to be told

In 2014, I was co-directing a feature-length animated film that was not going well. It wasn’t a good fit for me, so I left a well-paying project when I had nothing else lined up. Everyone thought I was completely booked with work, but I wasn’t, so I had to get started on a project right away. This story came to mind and I felt compelled to do it because I cared about it deeply.

I looked for a different, more poetic approach, looking at the illness from the perspective of someone affected by it, but not seeing it right away as suffering. The suffering is shifted to the background, to the perspective of my main character, Jacqueline’s daughter.

Fun with translation

I thought it would be fun to set the film on a train, with this old woman losing her head. I wanted the English title to be The Head Vanishes, because it was important to me to make reference to Alfred Hitchcock’s film The Lady Vanishes, which I loved. My film talks about an old lady, and Hitchcock’s film was also about an older woman who disappeared. I was told the translation was wrong, that it should be The Vanishing Head. But I stood my ground on that.

Train travels

Trains are like rain in cinema – extremely photogenic. Before making this film, I spent a lot of time watching films about trains and films that take place on trains. Trains are enchanting, magical. They tell such great stories. After my son took a train, I asked him what he did and he simply said: “I looked out the window.” I find that lovely, because most of the time when I take the train, I don’t look out the window.

There’s a meditative side to looking out the window of a train, even a melancholic one, as we think of different things. I thought the setting of a train was ideal for telling Jacqueline’s story, following her train of thought and her inner journey. The train also reminds me so much of my own childhood when my mother would take me to Spain. We’d take all kinds of trains, including overnight trains. We’d wake up in the morning and see the Mediterranean Sea. That whole nostalgic side of it appealed to me. I chose a palette of muted colors that weren’t aggressive or cold. I wanted the images to be stimulating, but not garish.

Playing with proportions

I worked with a graphic style and device that’s similar to one I’ve used in previous films, where I emphasized differences in height: We see a very small lady and the extremely tall woman pursuing her, who turns out to be her daughter. What interested me was that when you’re stricken with this illness, there’s the tendency to be treated like a child by the people around you. That’s what happened to this woman: it turned her daughter into her mother and vice versa. So that’s where the difference in size came from. I also used gentler imagery when Jacqueline’s feelings became more pronounced.

It’s all in the details

My acting training comes in handy when I write, because I know how I want my characters to move and express themselves. It’s hard to communicate to my animators exactly what I’m looking for, so I work with very detailed 3D animatics, which saves time afterwards. I used 3D models – before they were rendered into final characters – that respected the right dimension and scale, which enabled me to be perfectly calibrated in the frames, the rhythm, and the action. In this film, I used specific actor references for both characters. I wanted very economical movements. I prefer simple animation, where each look has meaning and importance. If a character is looking somewhere, it’s for a specific reason. That’s where my skills as an actor and director come in. I tend to direct my animators the same way I’d direct my actors.

Guiding principles

I always use guide tracks of music similar to what I’m looking for in my animatics. Then Pierre Caillet, my composer, proposes ideas. We really understand each other, because we’ve known each other for such a long time and have collaborated many times. For Jacqueline’s animatics, I used music by a jazz composer I really like – Akosh.

My vision stayed the same throughout. For the scene where Jacqueline’s daughter is chasing her, for example, I asked Pierre to compose music that was fairly deconstructed and very violent. I wanted to express Jacqueline’s feelings with music – the violence she sensed at being pursued. I didn’t want to show that imagery onscreen; I wanted to show order and phantasmagoria, not the anxiety. But the music is violent – the psychological violence felt by Jacqueline. We recorded the music in Paris, and the NFB took care of the sound design, effects and mix, as well as the English narration. They did a splendid job.

I love birds and fish – it’s a bit of an obsession, really, and I wanted Jacqueline’s daughter to seem like a bird. But the idea of adding pigeon sounds to her to make her seem even more of a nuisance was my co-producer Julie Roy’s idea. It was very well executed by Pierre Yves Drapeau, my sound designer.

Comic relief

I’d have to say that the scene with the chickens running around the kitchen is my favorite. It’s so completely absurd. It’s so ridiculous that I just loved it. And what I especially adore is that Jacqueline tells this story as if it were all perfectly normal!

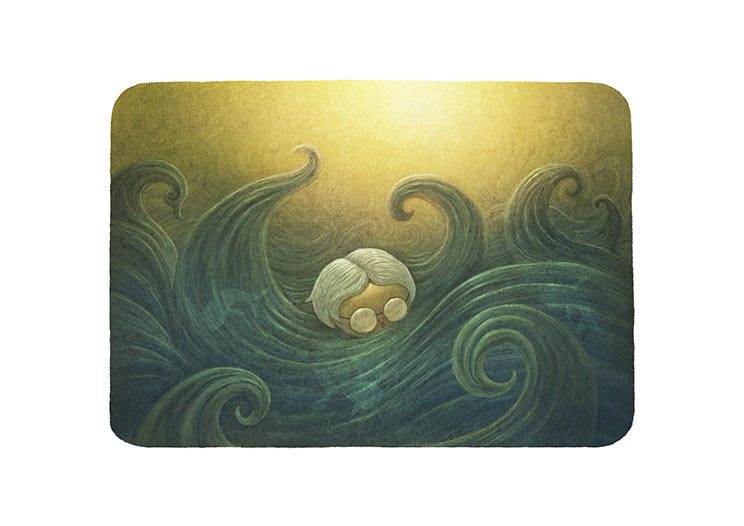

Lost at sea

For this type of disease, I wanted to tell this story respectfully. As much as you can experience short remissions with dementia, we know that this type of pathology condemns people to a certain outcome. There’s no possible cure. Telling this story otherwise would’ve been very inappropriate and in poor taste. Yet it was important to me that the film’s final scene depict a certain tenderness, because these types of lovely moments between people with dementia happen all the time, thankfully. We recognize our people, and then – poof! – they’re gone again.