How ‘My Favorite War’ Uses Animation As A Memoir Of Finding Freedom

As a little girl growing up in Cold War Latvia, Ilze Burkovska-Jacobsen found German bones in her sandbox. Wondering why her mother had trouble buying butter when the school cook was taking food home, she started digging for the truth. Decades later, as an International Emmy award-winning filmmaker with more than 15 hours of tv animation and documentaries to her name, she is still digging.

Memories of her childhood are at the heart of Ilze’s animated memoir My Favorite War. The feature won the Contrechamp award at last year’s Annecy Festival, where she was the only female director in competition, and is now in the running for best animated feature at the Academy Awards and best indie film at the Annie Awards.

Ilze’s childhood in Soviet-era Latvia was marked by happiness on her grandfather’s farm. He had been forcibly deported to Siberia earlier in his life; his time there had taken a toll on him, but hadn’t extinguished his creative drive as a painter — or his commitment to listening illegally to Voice of America broadcasts, in order to hear news that was not propaganda. Uncovering lies moved a young Ilze to pursue journalism, even as cracks appeared in the Soviet Union in the late 1980s.

Fear of World War 2 and the enemy threat of the Cold War had been drilled into her generation, but Gorbachev opened the door in the 1980s and Ilze slipped through it. A school petition to end compulsory arms training was successful — even the school principal could see the writing was on the wall for the regime. Seeing how eloquence and persistence had paid off, Ilze was able to go abroad to study journalism in free Norway.

There, she decided to pursue a career in television. With her producer-director husband Trond Jacobsen and their production company Bivrost Film, she has made eight documentaries and several animated documentary series for children, covering sensitive topics such as abuse and violence. With some of the same team that created My Favorite War, Bivrost Film won an International Emmy for the animated series My Body Belongs to Me in 2018.

The medium of animation was a natural choice for Ilze. During the Soviet Era, Latvia was renowned for its lyrical puppet and hand-drawn animation for children. These works embraced poetic concepts with very high production values, never underestimating their young audiences. The medium’s playfulness allowed for some freedom of expression, however veiled. Even today, Latvia is well known for its auteur animation, such as 2019’s Annecy Contrechamp winner Away by Gints Zilbalodis and Signe Baumane’s Rocks in My Pockets, which was distributed in the U.S. in 2014.

What made Ilze decide, ten years ago, to turn the camera on herself — following in the cut-out footsteps of Roze Stiebra, the grand dame of Latvian animation — for a feature-length film aimed at adults and teenagers? The director explains below:

Burkovska-Jacobsen: I thought my story could be useful for other people in the world. We are dealing with a collective trauma of an oppressive regime. The Soviet Union wanted us to love war as a unifying platform. Judging from the awards we received in Korea and Japan, and sold-out screenings in Hong Kong and Belarus, our story of a young girl finding freedom seems to be resonating.

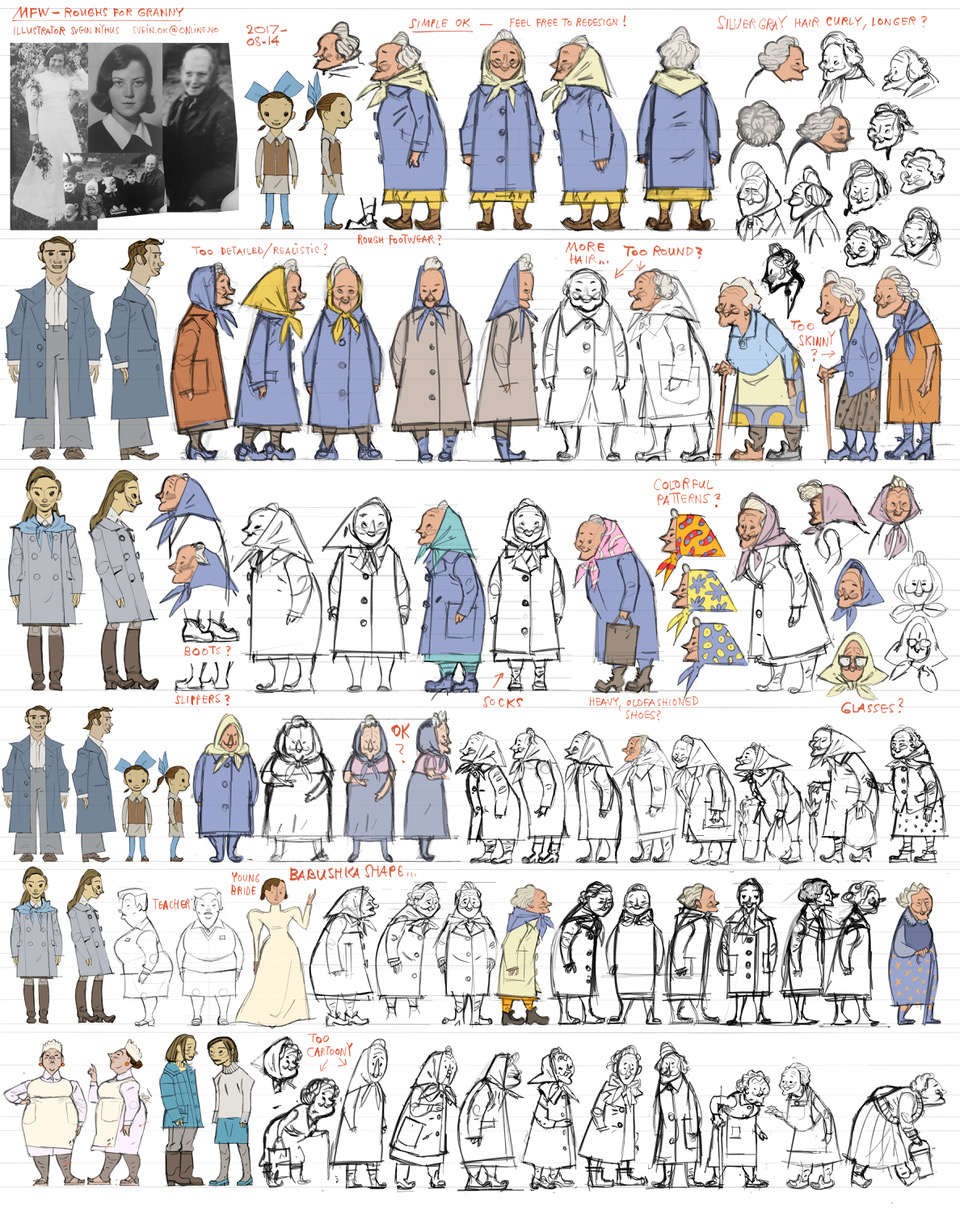

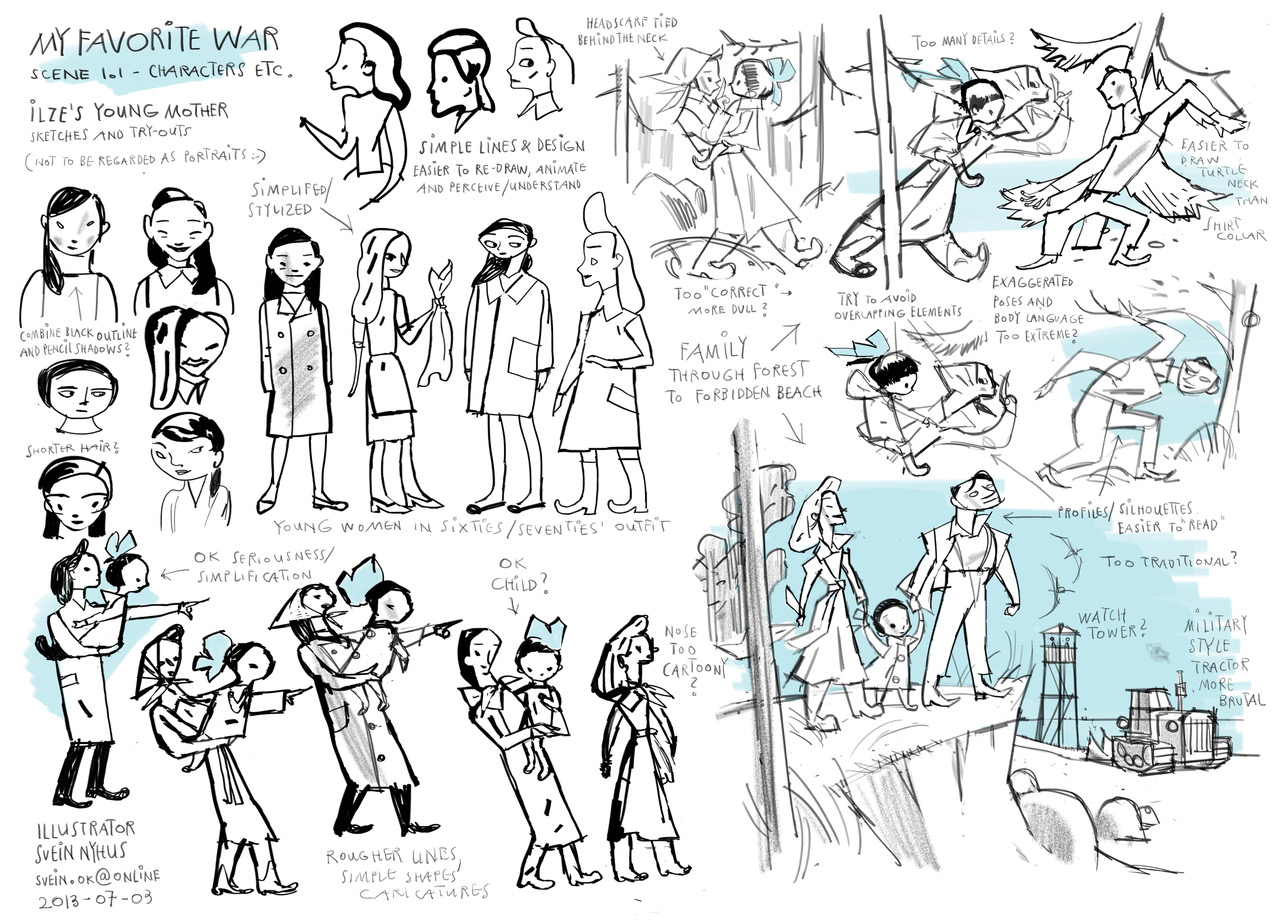

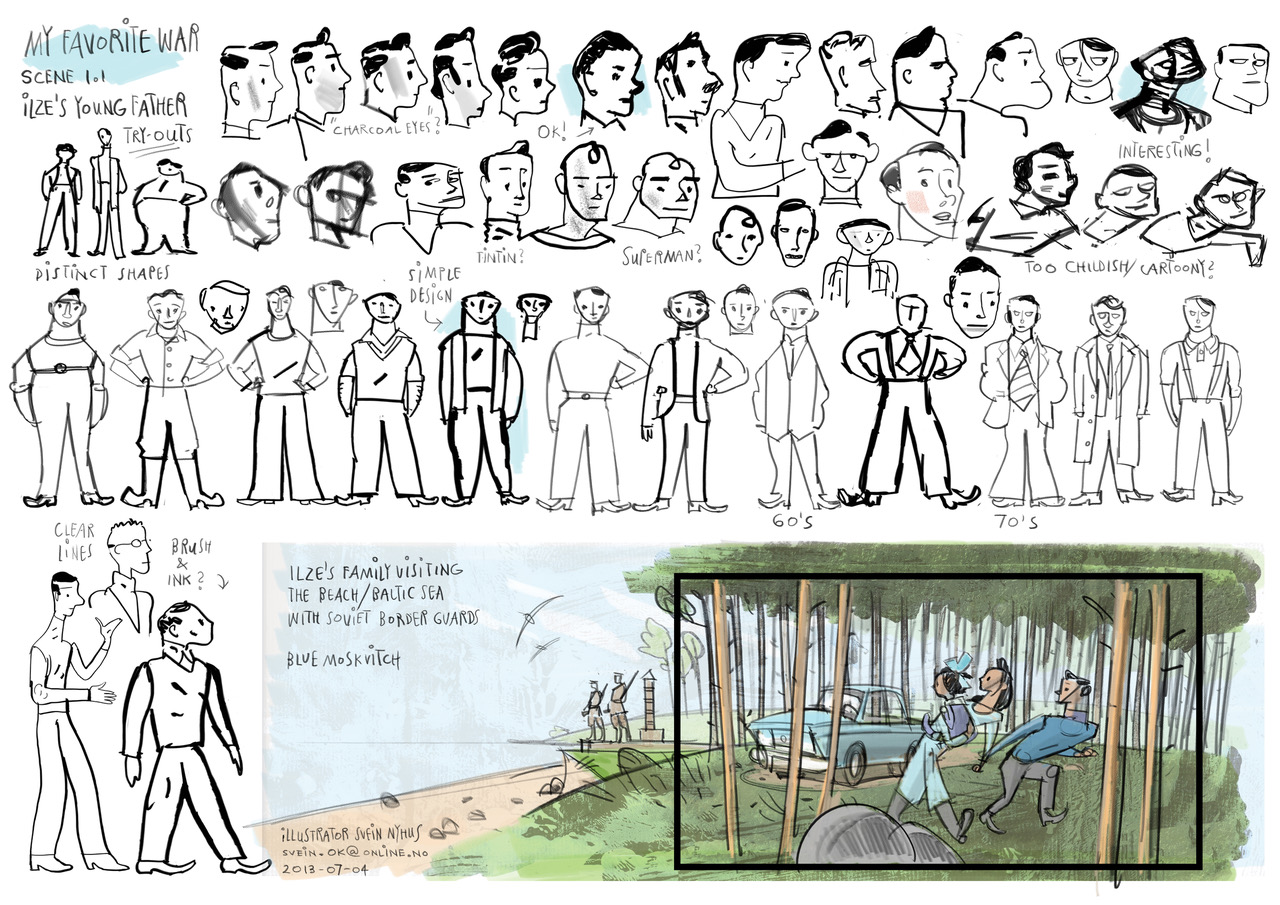

Our first step was to work with the Norwegian children’s-book writer and illustrator Svein Nyhus as our concept artist. He can draw people in funny positions with cartoonish looks, but they can be difficult to transform into animation. Svein would say: “You have to make it work for the duration of a whole feature. Sometimes it’s hard to listen to poetry for 90 minutes.”

Around the same time, in 2011, our Latvian producer Guntis Trekteris from Ego Media secured script development funding in Latvia. The characters were adapted by Krišjānis Ābols. Harry Grundmann, one of Latvia’s top illustrators, did the children and army characters. Background artist Laima Puntule made sure every detail in my childhood was accurate.

Character animators Kerija Arne and Arnis Zemitis, and 3d model makers and animators Neil Hammer and Toms Burāns, all made sure Svein’s concept art was given life. Initially each animator would get a scene within one episode, but we realized we would have better continuity with one animator per episode.

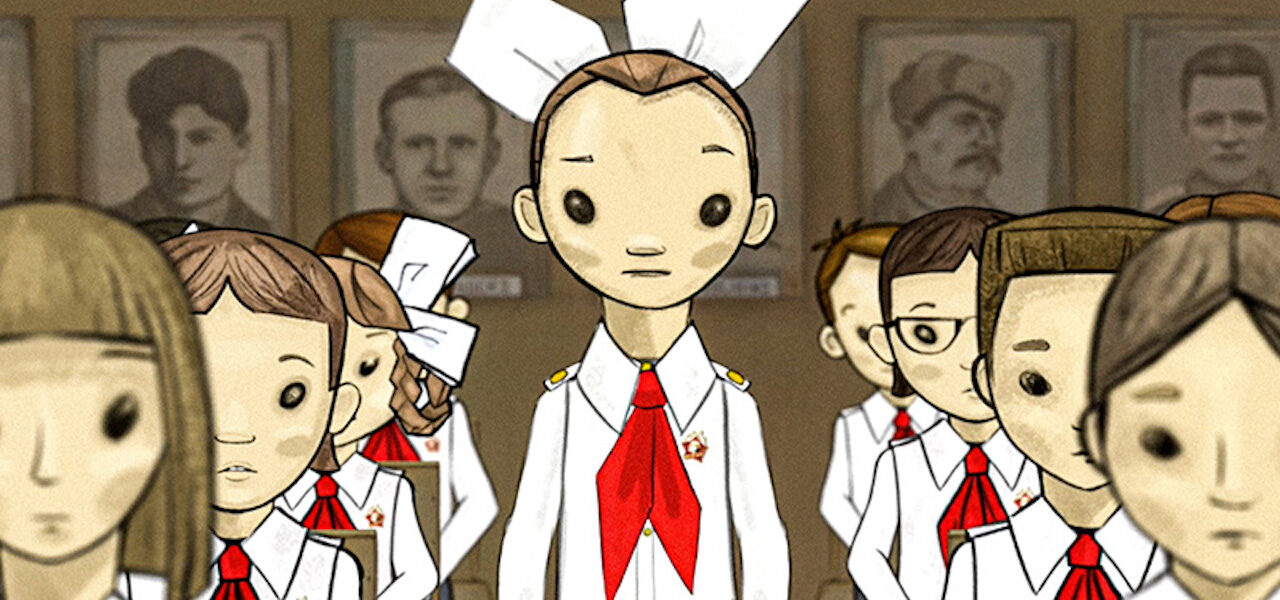

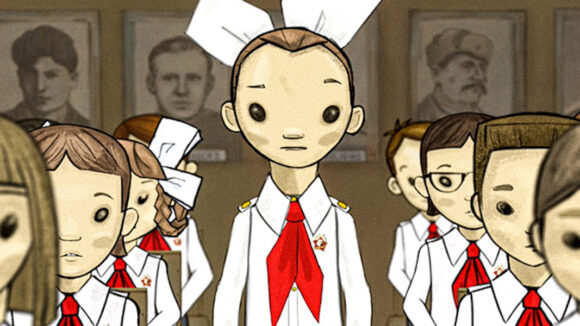

For me, color coding was crucial. I knew from the beginning I wanted to use gray for Soviet locations — my mother’s workplace, the shops, our apartment building — to create a mood of un-freedom. We use the red color as an aggressive contrast, which throws itself into our daily life, like a disturbance. The war scenes were done in sepia to show that they are flashbacks from before the Cold War, like an old photograph. Thinking of color really helped me imagine when I was writing the story.

My grandfather’s world had to be in bright colors — blossoming flowers, blue skies — to show that there is a happy childhood outside the Soviet Union. Already in the 1970s, the Soviets were in trouble economically and they needed the kind of private farming that my grandfather did (for which he was actually deported to Siberia, initially).

When you look at the film like a documentary maker, there are so many questions about the historical context. But, as an animator, you have to take out things that are a challenge to understand for a wider audience.

My Favorite War Contest

Win one of these collectables: pins of Soviet Winnie The Pooh or Wolf & Rabbit, or a Latvian figurine used in the film. To enter, accessorize these gentlemen below by creating your own prop, graffiti, or stencil art. Send in your idea as a 3000px wide .png file with transparent background to myfavoritewarfilm@gmail.com before March 1.

.png)