Dave Pruiksma Passes On The Disney Nine Old Men’s Lessons To Young Animators At CAT Animation

Dave Pruiksma learned animation from the best. Hired by Disney in 1981, he was mentored by Eric Larson and guided by other members of the so-called Nine Old Men — the core group of animators that formed around Walt Disney.

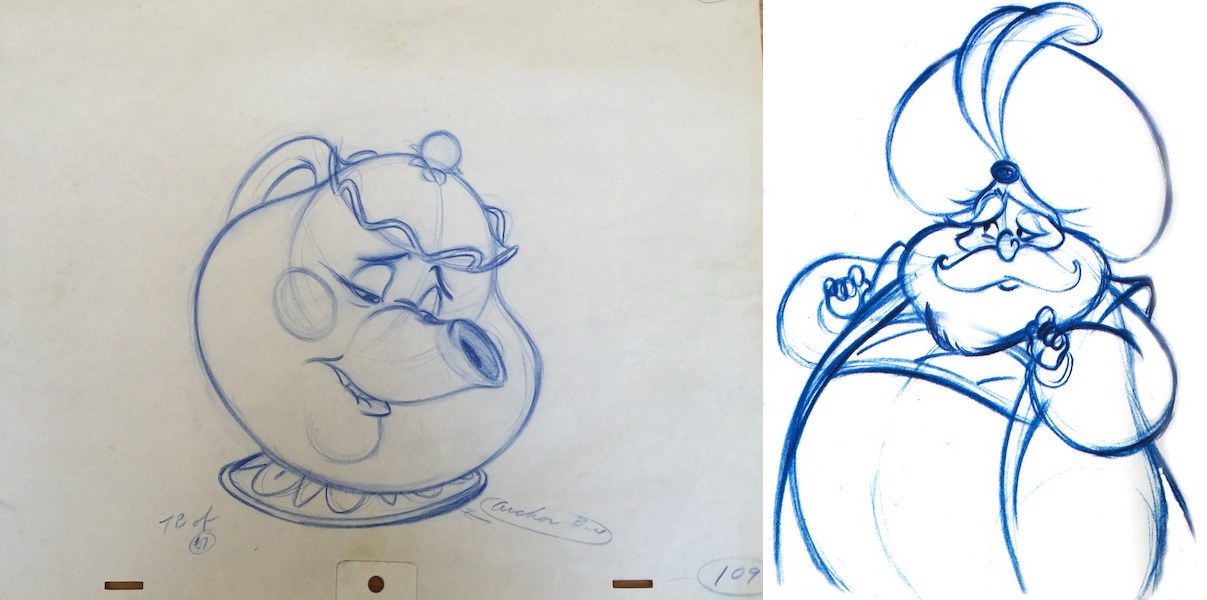

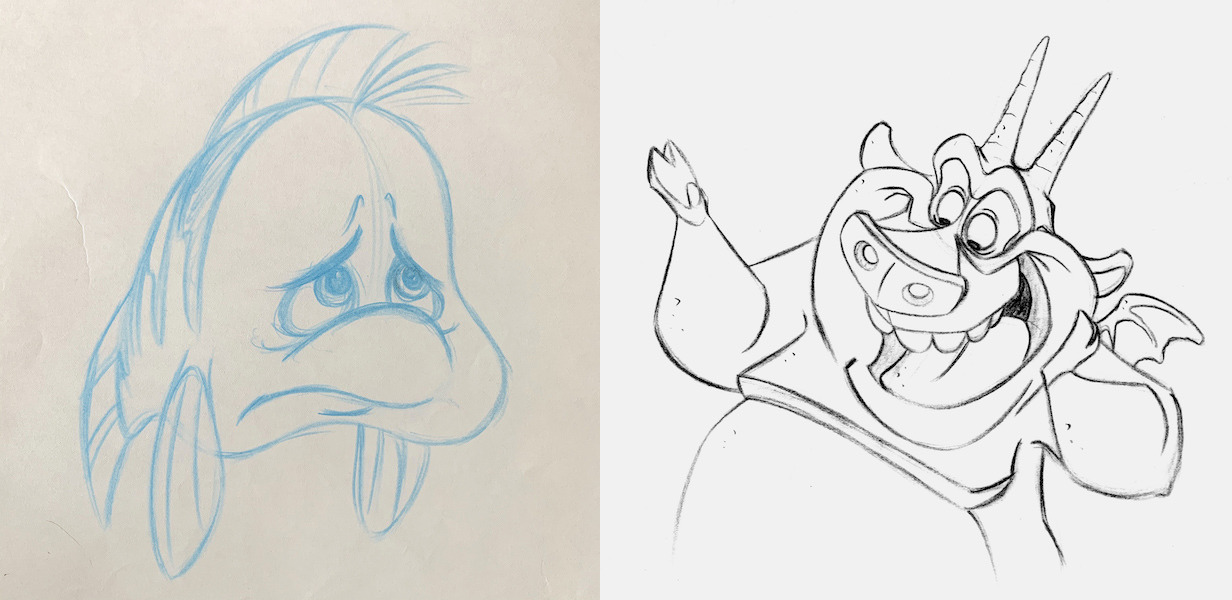

Pruiskma went on to become a supervising animator at the studio, bringing to life such classic characters as Mrs. Potts and Chip in Beauty and the Beast, the Sultan from Aladdin, Flit in Pocahontas, the gargoyles Victor and Hugo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Mrs. Packard from Atlantis: The Lost Empire. He was also an animator on The Little Mermaid, The Lion King, The Rescuers Down Under, The Great Mouse Detective, Oliver & Company, and Cranium Command.

Having amassed decades of experience in animation, Pruiksma is in turn mentoring the next generation at CAT Animation, the online school he co-founded. Below, he recounts his journey to this point. Over to Pruiksma:

I arrived for my first day at work in the classic art deco building located on the corner of Mickey Avenue and Dopey Drive on August 31, 1981. That day, my colleagues from Calarts and I started in the feature animation department at Walt Disney Productions. We were introduced to all the technical aspects of film production at that time: the camera department, editing, ink and paint, and even the archive of original animation drawings (affectionately called “The Morgue.”)

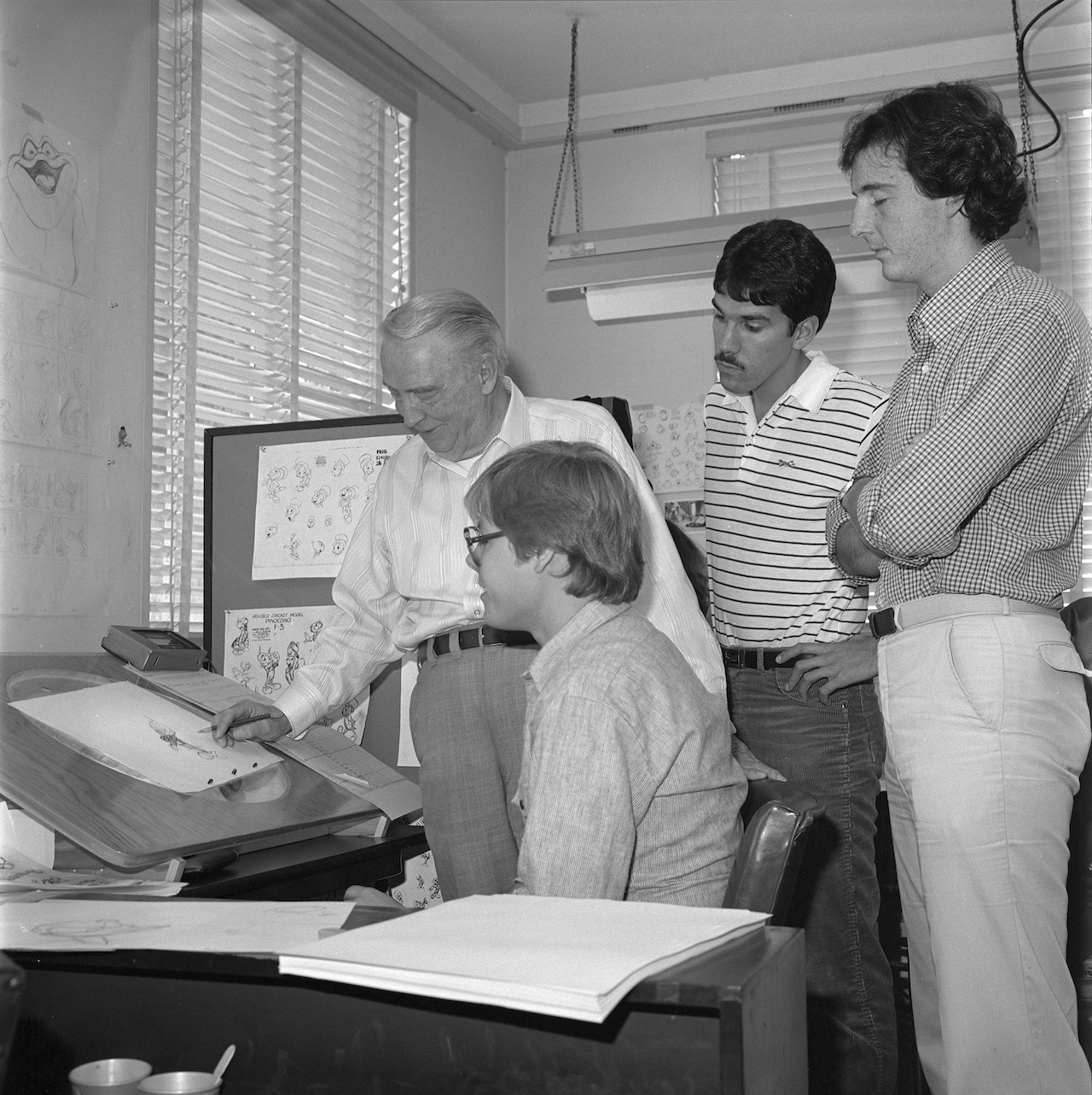

Since then, much of animation production has changed, but what I would soon learn about the approach to quality character-driven animation would prove to be far more valuable. That started when we were introduced to Eric Larson, one of Walt’s hand-picked Nine Old Men, who would become our first mentor and shape the way I looked at and approached animation for the rest of my career.

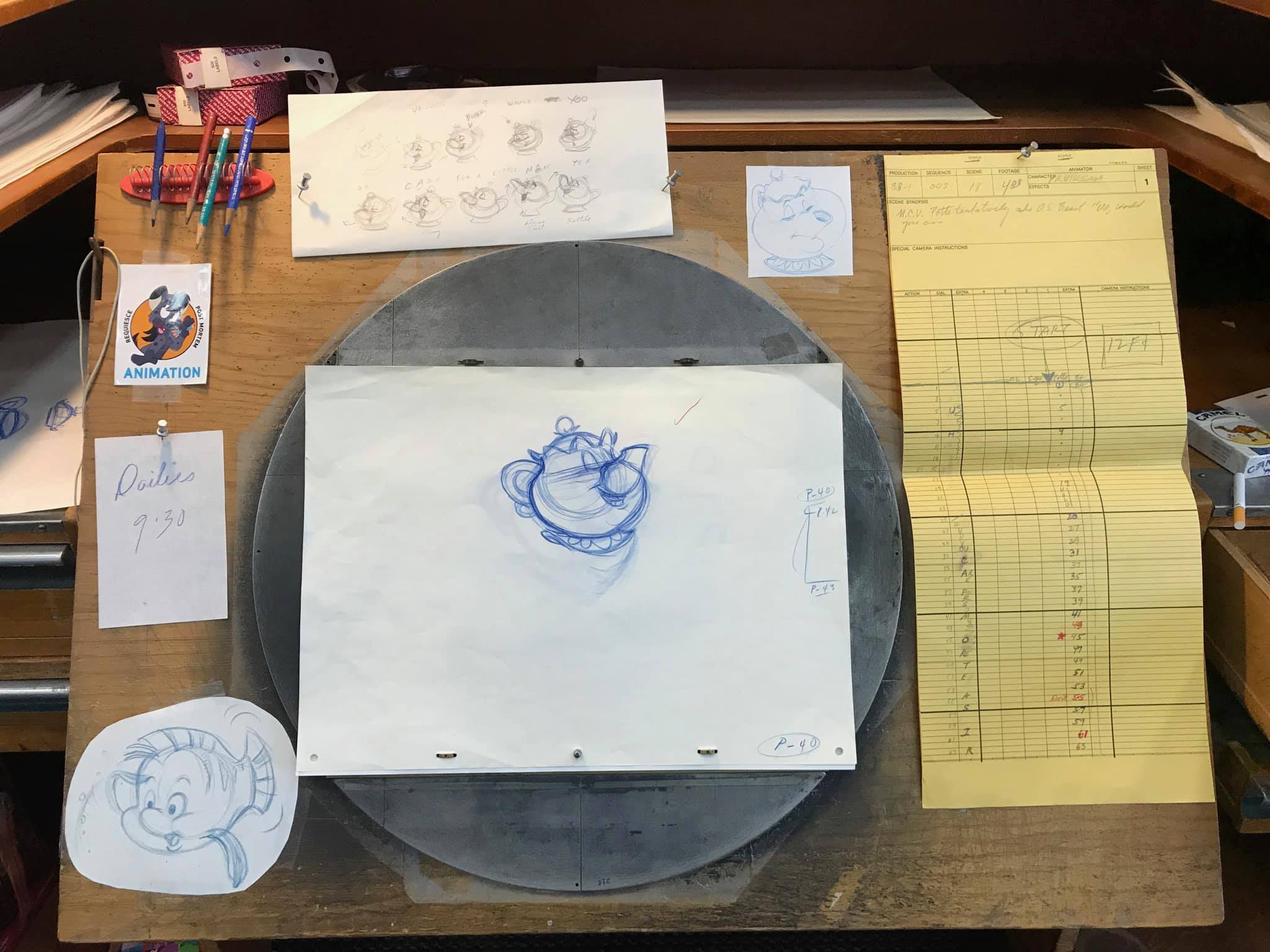

Eric was a kind and gentle soul. Very patient and very nurturing. A natural teacher. He would talk to us about what we wanted to communicate in our work and then gently guide us in just how to do that. He would do this by laying a clean sheet of paper over our drawings and doing a “diagram,” as he called it — a drawing showing how we could strengthen a pose. Sometimes these diagrams would be radically different from what we had drawn. Other times it would be a simple correction to the tilt of the head, or some other tweak that would add the life the scene was missing.

Eric’s approach began changing my perspective on animation: he discussed character and not drawings. His focus was on performance over technique. I see now that before working with Eric, I was just emulating what I saw in other work without fully understanding it. Eric not only showed me a better way to look at animation, he told me why.

To Eric, it was not about individual images — it was about the flow of drawings moving from one to the other as they illustrated a performance. This was not merely about motion — it was about emotion. Always encouraging, he never made you feel bad for not knowing. He just showed you animation from another vantage point.

I admit that sometimes, while looking over his shoulder, I would not understand what he was doing, but he always patiently explained why he was doing it and that made all the difference. Sometimes, years later, I would be animating a character and his words would come back to me. I would smile, because now I understood what he had been teaching; it had become a part of me.

Over time at the studio, I met a number of the other surviving Nine Old Men who, though retired, always seemed to be around the place, keeping a watchful eye on a new generation’s progress and growth. Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston were at the studio frequently, working on their first book, The Illusion of Life. I found they echoed what I learned from Eric: that drawings are the tools and character is the reason for the tools.

Frank and Ollie spoke of their characters in the third person, like actors do when they discuss their work, and I started to realize that these characters were as real to them as I was. I saw this in their final work at the studio, for The Fox and the Hound. In the introduction of the two titular characters, Frank and Ollie worked alongside the younger animators, and it was apparent that there was something unique about the pair’s work when it came on the screen. An extra spark of life separated their scenes from the rest.

This does not denigrate the work of the younger artists at that time, but just showcases what these masters had been talking about: believability and sincerity over technique. Frank and Ollie showed me that I could not expect an audience to believe these sequential drawings were real if I did not believe it myself. They taught me that the characters had to have their own humanity, whether a mouse, a puppet, or even a doorknob. They showed me how to make the characters think and feel in a way that was relatable to audiences.

Through their teaching, I learned that I should not just draw symbols for emotions but actually reach deep inside myself, discover what those emotions feel like, then get that down on the paper. By following their guidance, I almost immediately saw a jump in the depth of my work, because I was no longer just emulating. It was real and it came from inside me.

This tendency to talk about character, personality, and believability over technique was the common thread whenever I spoke to animators from the first golden age, both Disney and non-Disney. Though I realized the importance of these principles early on and worked towards that goal, it really didn’t hit me how important they were until a number of years into my career, as I sat in a studio screening room watching the work-in-progress reel of The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

It all came together as I was watching one of my scenes when, for the first time ever, I realized I was no longer looking at drawings — I was looking at characters. As an animator, I had fooled myself into believing that sequential drawings were now indeed alive and separate entities, even while knowing the process I had used to create this illusion. It was the most exciting moment of my career. I had finally achieved my goal: the thing the old guys talked about nearly constantly, the spark of life that made it as real for me as it was for the audience. The illusion of life.

This is why I now mentor young artists through CAT Animation (Classical Art Training), an online school I started with my colleague Dave Kuhn. I want to share this unique perspective — what I discovered about the most important things to remember in animation: character, personality, and performance above all else.

With the passage of time and the growth in technology, I feel that these vital aspects of animation are not given the focus and importance they deserve. We have wonderful new tools that have pushed the boundaries of the medium, but they should be supporting the characters, stories, and entertainment rather than driving it.

I teach because I believe that another renaissance can and will happen in animation. I would like to know that when it does come, the young artists of today will be ready, by focusing on what have always been the most important aspects of character animation. I want to give back what I learned in my time in production to a new generation, just as the last generation did to us.

The next session at CAT Animation starts in January. To learn more about the classes and personal mentoring CAT Animation offers, visit the school’s official website.