CAT Animation Tutor Pixote Hunt On How To Become An Art Director: Don’t Worry About Style, Find Your Voice

Pixote Hunt’s career in animation spans over 40 years. He has had the opportunity be a director and art director on both feature films and shorts, yet he retains the same enthusiasm for the possibilities of the medium as when he first started.

He is now sharing his knowledge with a new generation of artists at CAT Animation, an online school founded by Dave Kuhn and Dave Pruiksma. Hunt took time recently to sit down with the two Daves to discuss his passion for art direction and why it’s a crucial part of any production.

These days, the position of art director seems to be a rather misunderstood part of the animation process. Many people use the term almost interchangeably with visual development. As Hunt puts it:

I think they were using these phrases quite liberally, back and forth. If I were to sit down with them, chances are it’s the visual development aspect of filmmaking that they’re talking about. But it’s different than what you can Google about the flashy paint splatters and derivative design shapes that are loosely termed as art direction.

Some people believe that art direction is developing one’s own specific style and applying that style, like a template, to whatever project they are on. Hunt disagrees:

The position of art director is such a wonderful opportunity to reinvent yourself over and over. I think the first thing that comes to mind whenever I get a script is, “Oh my God!” — because I don’t know what’s going to happen next, I’m not really sure at first, and that’s so exciting.

When asked what he feels is an art director’s job in animation, Hunt says:

I believe the art director’s job is to show the film’s leaders what their film could look like. First, we start with the biggest picture, something so big that it doesn’t appear in anyone’s film.

We are “world builders”: we build that world to give the directors and producers opportunities to home in and get closer and closer to what they want. And finally, we’ll come up with an establishing shot that is suitable for the film, with everything harmonious and as if from one hand. But we’re “world builders” first.

As for the character designs, the world is open. We consider character designs as a casting director does, meaning, “Here is who I think might fit these opportunities.” Let’s start the conversation by talking about who these characters might be. If we need to change the direction or refine the direction that we’re going in, we do.

Hunt’s patient, soft-spoken demeanor can’t disguise his unbridled exuberance over the art of animation and his good fortune in working with and learning from legends in the field: Eric Larson, Ted Kierscey, Mel Shaw, Walt Peregoy, and Iwao Takamoto.

Like many artists of his era, Hunt’s first real awareness of animation was from television and watching Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color (in black and white) at a very early age. Around that time, a neighbor drew a cartoon character for him, and it dawned on him that there were real people and artists who made animation. He thought:

People can make something [inanimate] live! With that I was hooked!

Hunt describes a seminal moment on his pathway to knowledge: when he was introduced to a clip from the 1958 Disneyland educational film 4 Artists Paint 1 Tree. The film shares the process and insights of four top Disney artists — Marc Davis, Eyvind Earle, Joshua Meador, and Walt Peregoy — as they paint the same subject matter. Hunt says:

I was just amazed at how an individual artist’s voice can be expressed, influence a whole body of work, and end up on the big screen.

After high school, Hunt studied at the prestigious School of Visual Arts, which led to animation work in New York and eventually Florida. It was while animating short sequences for Disney World that Hunt’s talent was brought to the attention of Eric Larson, one of Walt’s so-called Nine Old Men, who immediately offered the young artist an opportunity to train with him at the Disney Animation Studios in California.

Hunt leapt at the offer and, during those months of his training, enjoyed almost exclusive access to Larson and other top artists at the studio. After being successfully promoted from trainee, Hunt worked as an effects animator at Disney for nearly six years.

But, ultimately, it was his passion for the foundational artistic and design aspects of production that led the young artist to move to Hanna-Barbera, where he could develop greater skills in the area of visual development with renowned designers Iwao Takamoto and Walt Peregoy (whose work in 4 Artists Paint 1 Tree had inspired him in his youth). Says Hunt:

And that was the really beginning of that journey into the world of art direction for me. I was privileged enough to work with Peregoy (famed for, among other things, the dramatic styling of 1961’s One Hundred and One Dalmatians), and gain his insight into color and design, and even hi life and professional philosophies, for the next 30 years, until the end of his life.

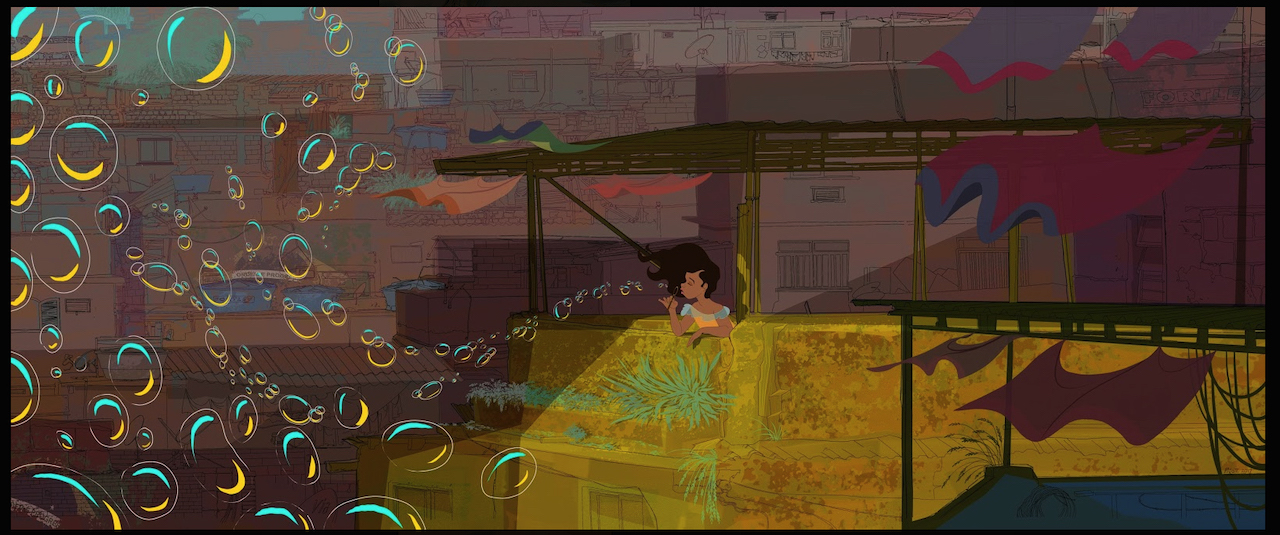

While at Hanna-Barbera, Hunt worked up to the positions of director and art director of the animated sequences in the feature film The Pagemaster. Afterwards, he returned to Disney Feature Animation, where he worked as art director for The Rescuers Down Under. He was subsequently director and art director for one of the more abstract pieces produced at Disney, the segment for Beethoven’s “Symphony No. 5” in Fantasia 2000 (image at top), and later the hauntingly beautiful short “One by One” for an unproduced future version of Fantasia.

Of his role at CAT Animation, Hunt says:

This art direction class I will be teaching for CAT Animation this summer semester is important to me, personally, because I have never experienced a class like this before. It is an opportunity for students to see the big picture.

What I hope students will take away from my class is, first of all, just experiencing and remembering that this is an art form. This is their voice. This is their contribution to what we love, what I love so much about this wonderful art of animation. It’s not just a title: it’s a real thing.

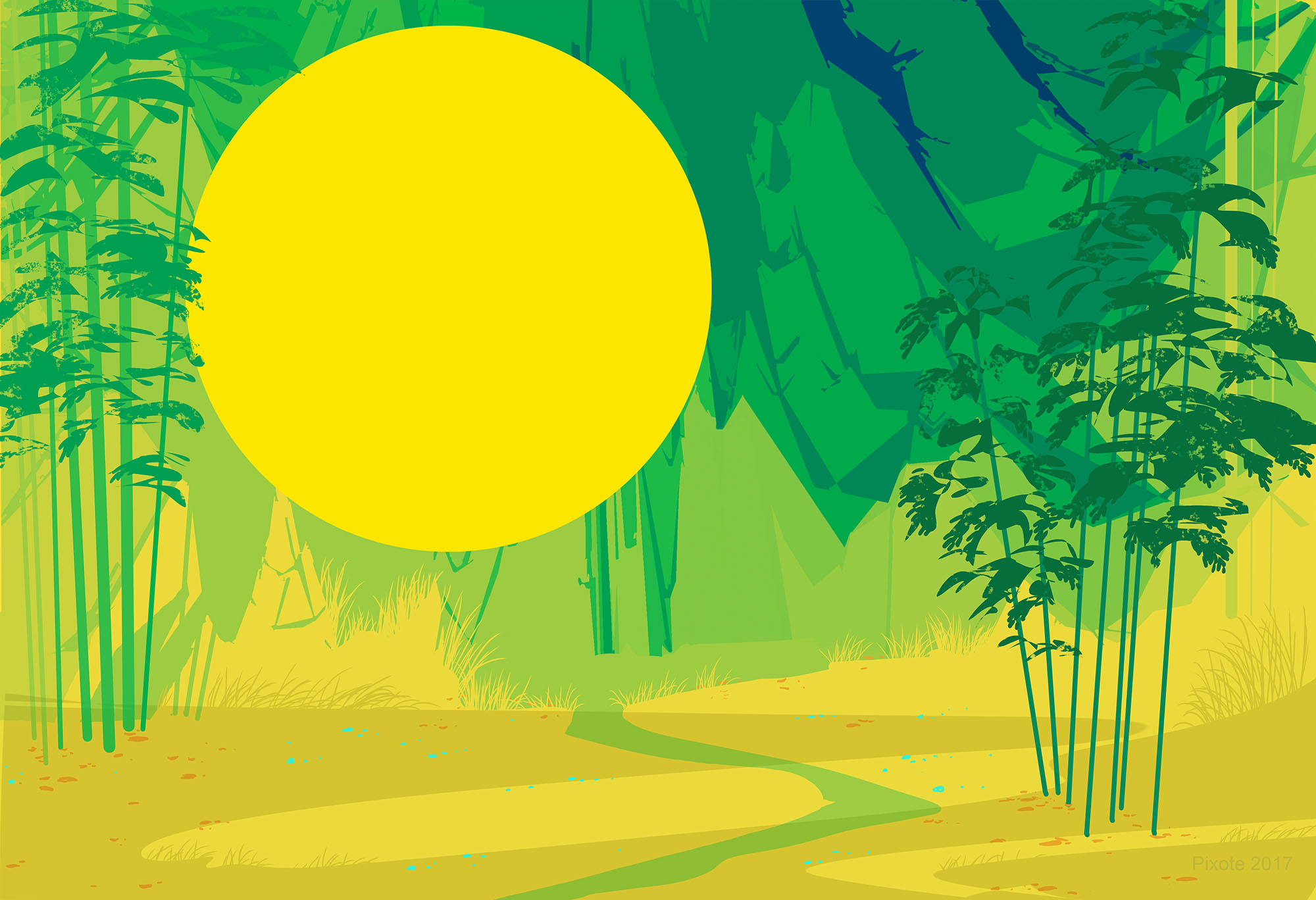

They’ll learn not to focus on how they can find “their” style. I am proud to say that I don’t have a style, and I will probably never have a style. I feel this way because I believe that each for film and art direction — each time one gets a chance to develop a film — the experience should be wonderfully different than the one before.

So, if I’m known as the person who does a particular shape of a particular tree, that’s kind of it. One-note. Done. What if your next opportunity is not that shape of tree, or a rock, or building? Then as an art director, you’re relying on some other mechanical way to get there.

So, rather than finding their style, I hope that my students will learn to find and cultivate their voice, which is how they see the world differently than the person next to them. Then, no matter what story is placed in front of them, the trained artist can see the world differently than the person next to them. And that’s as close to a style as I can possibly hope for any artist to get, as opposed to a formula.

The next session at CAT Animation starts in June. To learn more about the classes and personal mentoring CAT Animation offers, visit the school’s official website.

.png)