Unconventional Historical And Experimental Themes Enliven Thomas Renoldner’s Short ‘Stampfer Dreams’

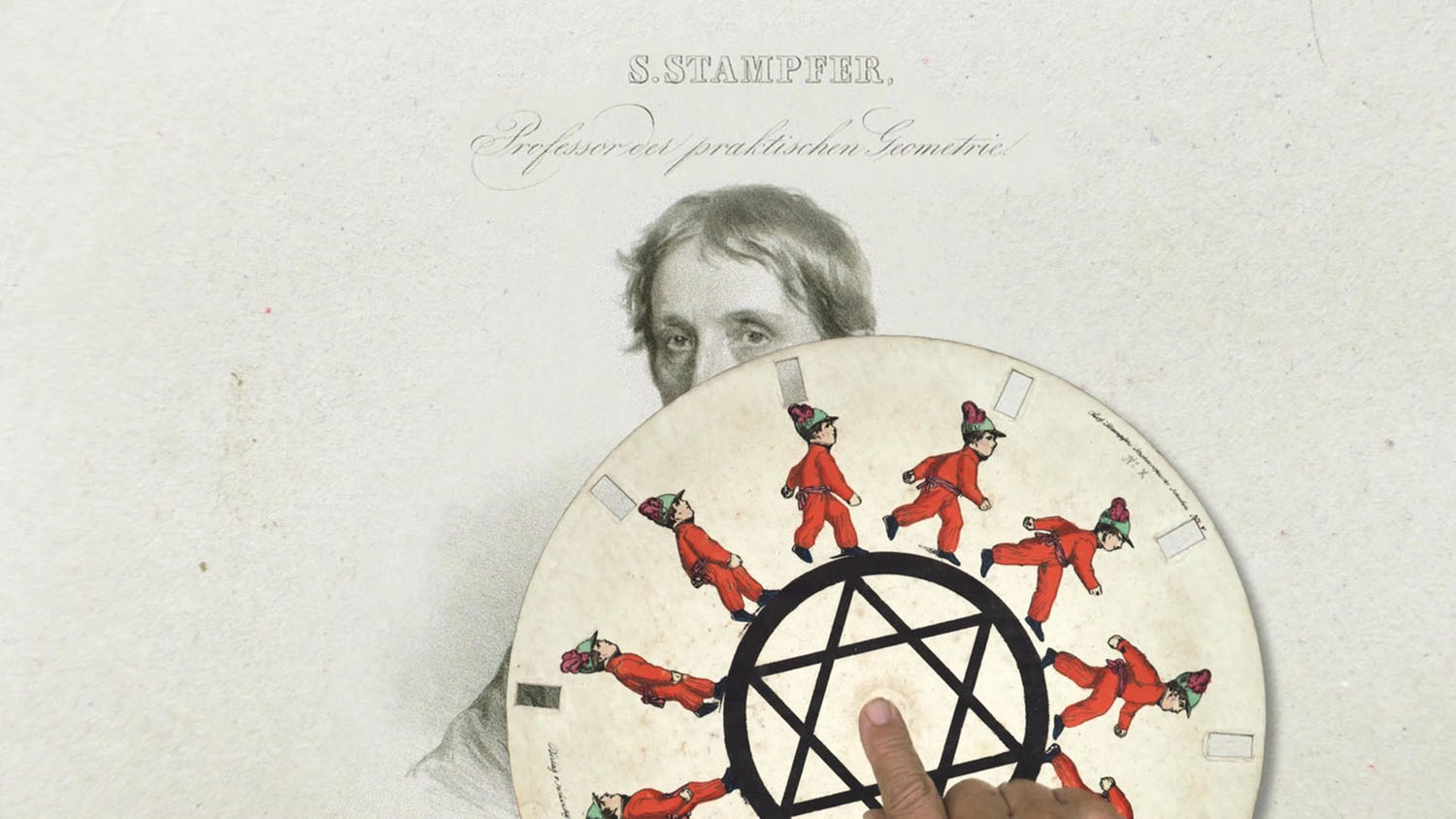

Thomas Renoldner’s Stampfer Dreams, which premiered at the 2024 Ottawa International Animation Festival, is a hypnotic and visually captivating 12-minute tribute to 19th-century animation pioneer, Simon von Stampfer. The Austrian scientist, in 1833, introduced the invention of stroboscopic ‘optical magic discs,’ precursor to the zoetrope, where slots in a rotating viewer created the illusion of movement in hand-rendered keyframe images.

By combining sequences from Stampfer’s original discs, Renoldner crafts a mind-bending narrative that alternates between biography and abstract imagery. More than just a tribute to Stampfer, the film celebrates the intersections of technology, art, and animation.

Stampfer Dreams offers a contemporary perspective on the legacy of early optical devices while engaging with both historical and experimental aspects of film. According to Renoldner, the work navigates the boundaries between genres and categories in film art, which he finds overly restrictive.

Cartoon Brew spoke with Renoldner about the process behind his work, from preserving historical materials to his technical and artistic choices.

Who was Simon von Stampfer?

Understanding Stampfer Dreams begins with Simon von Stampfer and his stroboscopic discs, an invention that predates cinema by several decades. As Renoldner explains, “Simon von Stampfer (1790–1864) was a scientist with expertise in multiple disciplines, including mathematics, practical geometry, and astronomy. He invented several devices for these fields and, like [mathematician] Joseph Plateau, [he] studied [physicist] Michael Faraday’s experiments on optical illusion phenomena.”

Faraday’s studies on stroboscopic motion illusions, observed while examining rotating cogwheels on industrial machines, paved the way for Stampfer’s innovations. Faraday constructed a gear mechanism with two gears mounted on the same axle, allowing them to rotate in different directions and at varying speeds. “When looking through the slots of the front wheel at the second wheel,” Renoldner explained, “it appears as if [the wheel] is standing still when both wheels move at the same speed, or when the two wheels move at slightly different speeds, it appears to move slowly.”

He added, “Both Stampfer and Plateau were familiar with Faraday’s 1831 publication on these discoveries. Both independently conceived the idea of adding moving images to Faraday’s construction, which led to the separate invention of the phenakistoscope. This device became one of the earliest steps in the evolution of cinema.”

Resonance with Contemporary Animation

In the context of contemporary animation, Stampfer Dreams engages with current debates surrounding technology. Renoldner noted a division between two distinct groups: “The haters of AI and the lovers of vintage — if I can call it that ironically. My film, with its reference to ‘honest handmade art,’ might seem like a statement against AI. But since digital animation tools allow us to show Stampfer’s animations in perfect quality and at precisely controllable frame rates without losing the original visual integrity, I would say Stampfer Dreams is a perfect example of how modern technology can preserve historical sources while still moving forward. So, it can be seen as a statement of openness to both high-tech and old-school.”

Renoldner is enthusiastic about how Stampfer’s work intersects with contemporary animation practices: “The animations on Stampfer’s discs from 1833 are proof of [historian] Giannalberto Bendazzi’s statement that animation can cover a wide range of genres, from abstract to figurative and from narrative to experimental. What Stampfer created were endless short films, which today can be seen as forerunners of the ultra-short animations we now recognize as GIFs.”

Renoldner also observed a renewed interest in the phenakistoscope among contemporary artists. “The phenakistoscope seems to have had a kind of renaissance in art contexts, with artists using variations of it in installations,” he said. “It’s fascinating to see how such an early optical device continues to inspire new work.”

Reconstructing the Discs

To reconstruct the stroboscopic discs for Stampfer Dreams, Renoldner and his team accessed the entire collection of Stampfer’s discs at Kremsmünster Abbey, in Austria. “They are kept by Gerhard ‘Father Amand’ Kraml, the curator of the Natural History Museum, who gave us photographs of the original discs,” he said. “My main animators, Reinhold Bidner and Eni Brandner, used Photoshop and After Effects to isolate Stampfer’s animations from the background and to rearrange and combine them with background drawings by Linda Wolfsgruber and Christoph Rodler, following my storyboard for the narrative parts and my sample animations for the experimental sections.”

The technical process was a collaborative effort that included composer Christof Dienz, who had previously composed music for German television and short films. Renoldner explained: “The communicative process between me, my animators, and Christof was quite complex. We first offered Christof a rough version of the film, then received a digital sound version of the composition. Christof suggested stretching the composition for the third ‘dream’ in the circus scene. I asked for a few revisions to the music, and after it was recorded with the musicians, we adapted the final version of the animation to the completed music mix.”

Finding a Story

With the original discs featuring a range of 23 diverse animations, Renoldner spent significant time figuring out how to create a cohesive story from the animated loops. “Finding a story or structural concept was one of the most time-consuming parts of the four-year process,” Renoldner says. His concept was to create what he calls a “pre-cinema found footage film,” using only the sequences from Stampfer’s discs and combining them with appropriate backgrounds.

Early on, Renoldner settled on the theme of early industrialization, as he explains: “Some of the most fascinating Stampfer discs feature rotating wheels and gears, some of them combined with rhythmically bouncing hammers. Together, they symbolize the historical context of the industrial revolution. This theme was not only an aesthetic choice but also a reflection of the historical period in which Stampfer’s innovations emerged.”

Renoldner’s research included studies on the industrial revolution, child labor, and industrial facilities in the Vienna area: “I visited a revitalized hammer forge from the early 18th century powered by water wheels. It became clear to me that the rotating axle driven by a water wheel represented a fundamental mechanical principle that would later serve as a basic element for larger industrial plants.”

Renoldner also drew from Stampfer’s biography as a starting point for the film’s narrative: “I wanted to show the Alpine region of Stampfer’s youth at the beginning of the film, where he experiences a dream about future technological advancements. This dream, inspired by the power of a rotating wheel he sees in a farmer’s mill, sets the stage for the rest of the film. I used Stampfer’s naturalistic animations to create a narrative framework and the abstract and semi-abstract animations to depict Simon’s visions of the future as surreal dreams.”

Fusing Narrative and Non-Narrative

Stampfer Dreams is an unconventional blend of narrative and non-narrative elements, as well as historical and experimental approaches. Renoldner said: “It’s one of my main interests as an artist to question the dominant standards and clichés within different genres of film. I’ve been a curator and animation teacher for about 40 years, and I’ve seen a lot of repetitive ideas. With my work, I try to contradict the narrow-mindedness of certain genres and to build a bridge between animation and avant-garde film.”

Renoldner’s blending of genres is evident in Stampfer Dreams: “I confront the audience with a narrative structure and visual setting reminiscent of a movie for children, while the dream sequences follow avant-garde film strategies and contradict the expectations towards a classical narrative film.”

While Stampfer Dreams could be seen as educational — introducing historical devices to a wider audience — Renoldner insisted it is more than that: “It’s the first time I’ve used historical material in my work, but I felt it was necessary to give a voice to these important devices that led to the invention of cinema.”

Preserving the Discs

Preserving the physical integrity of the original stroboscopic discs was of utmost importance to Renoldner and his team. He explains: “Our aim was to preserve the original quality of these beautiful hand-colored lithographs. We cleaned up the images slightly, removing dirt and minor damage, and refreshed the colors to ensure they appeared vibrant on screen. But we didn’t want to lose the authenticity of the original material.”

By blending historical material with modern technology, Renoldner doesn’t just pay tribute to the past; he pushes the boundaries of both animation and experimental film. Stampfer Dreams celebrates the groundbreaking work of early optical inventors while reimagining how animation can continue to surprise and inspire.

The 12-minute film Stamper Dreams is currently screening on the animation festival circuit. An accompanying book by the same name, that includes an augmented reality component allowing the original ‘optical magic discs’ to be viewed in motion, has also been published.