U.K. Directors Nicolas Ménard And Jack Cunningham Release 3D-Printed Stop-Motion Project ‘Triple Bill’

Animators Nicolas Ménard and Jack Cunningham are kindred spirits.

The two met at Nexus Studios in 2014, and began collaborating in 2019. Now, they have formalized their creative partnership by launching as the directing duo Eastend Western, repped by Nexus.

Both are based in the U.K., although Ménard is Québécois and was born in Montréal before attending the Royal College of Art in London. Ménard’s 2016 short Wednesday With Goddard won best animated short at South By Southwest film festival.

Cunningham’s work has included projects for Google, Vitra, The New York Times, and an augmented-reality app for the Obama Administration, 1600, that allowed viewers to conjure 3d animation of the White House from a dollar bill.

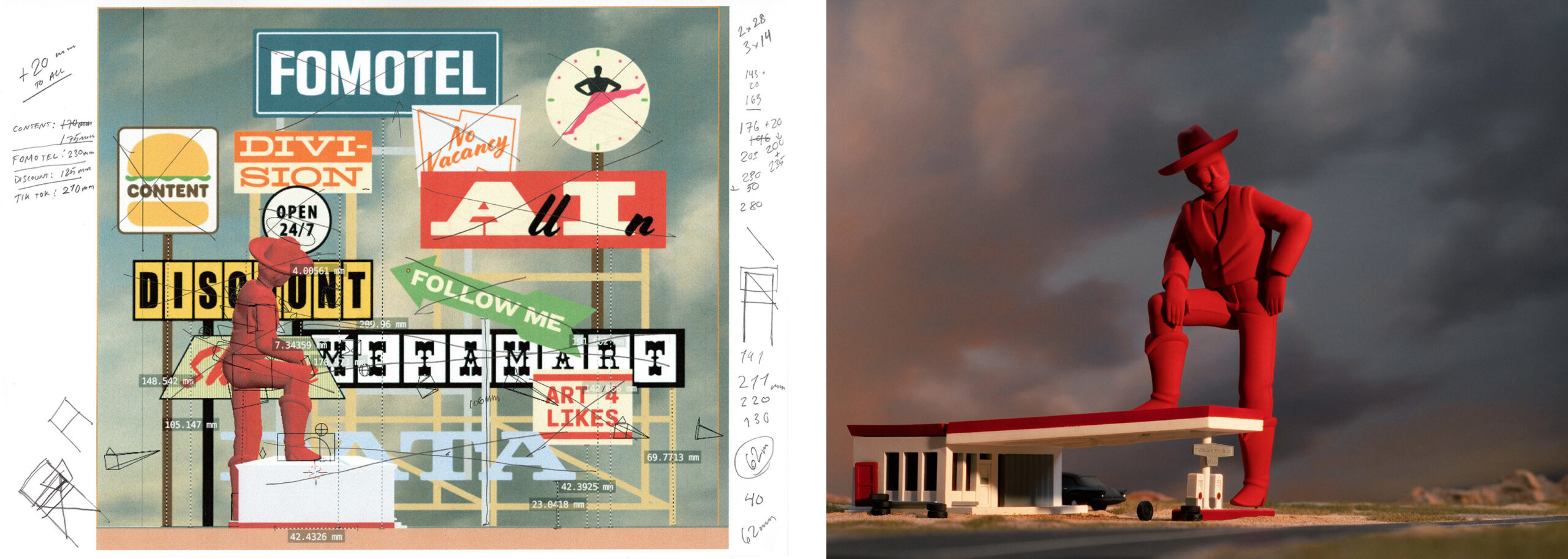

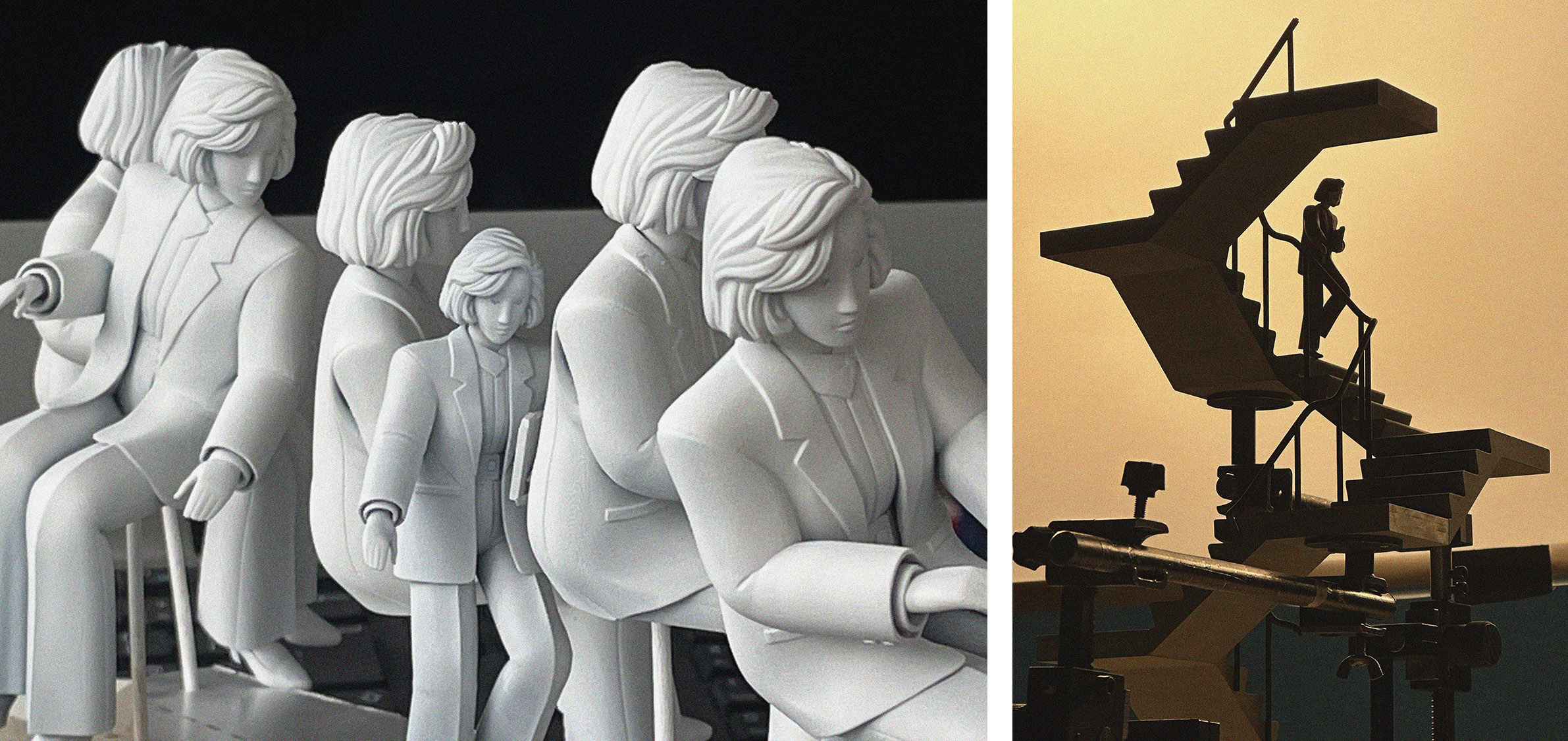

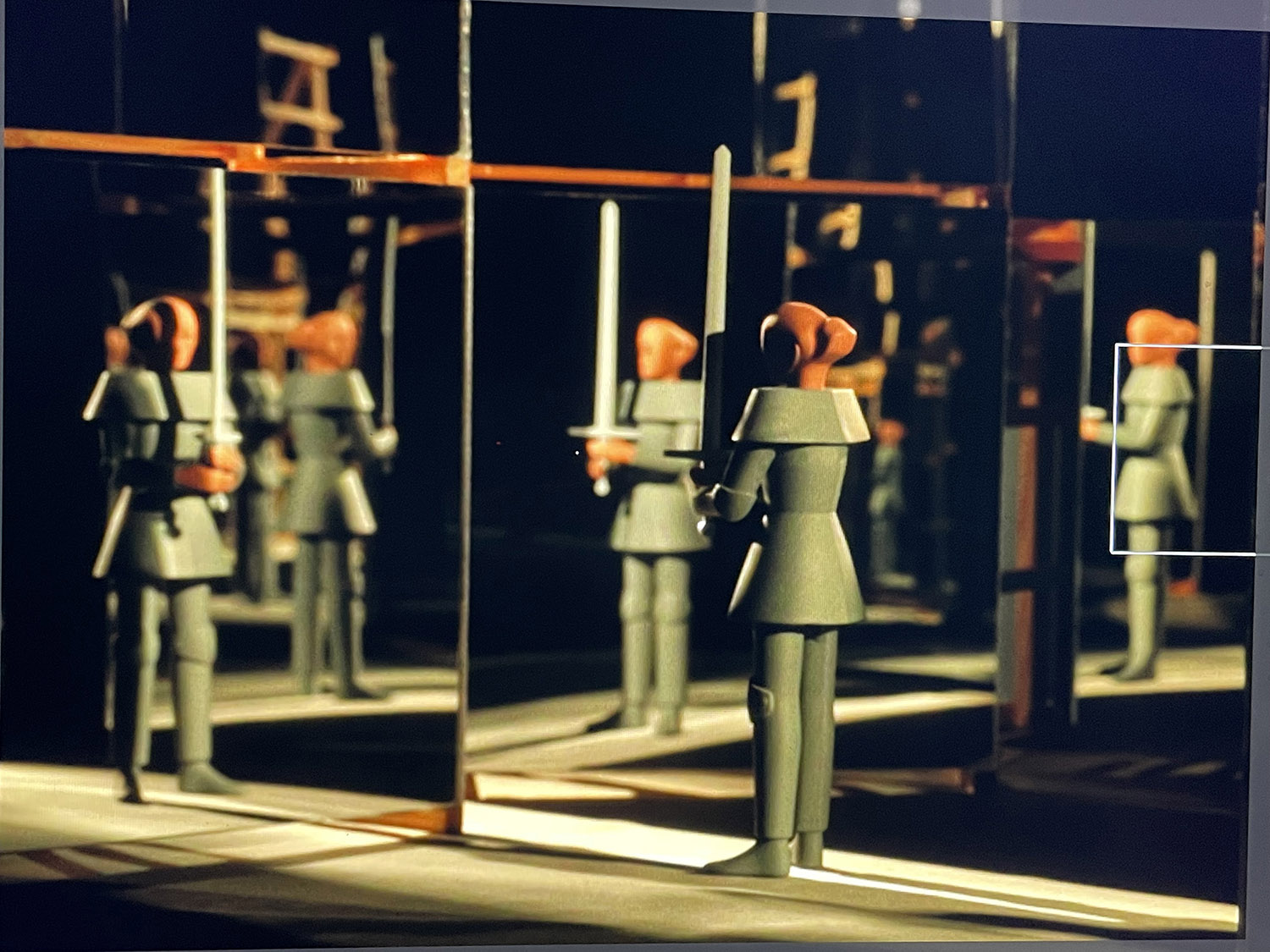

To celebrate the debut of their partnership, Ménard and Cunningham have released Triple Bill, a trilogy of short animated films, each under two minutes. The shorts — unique mood pieces that Ménard describes as “a Western, a film noir, and a fantasy film — continue the filmmakers’ fascination with replacement animation, using delicately-rendered miniatures to bring to life stop-motion characters.

Eastend Western created Triple Bill over a year-and-a-half, working with director of photography Ian Forbes in three shooting blocks at Arch Model Studio, a stop-motion specialist production facility. They then finessed the trilogy with other friends and collaborators who contributed to the passion project. Cartoon Brew spoke with Ménard and Cunningham to discuss Triple Bill’s creation, and their love for the tactile animation medium, which they recently showcased in an art exhibition near their London studio.

Cartoon Brew: What was your creative inspiration for Triple Bill?

Nicolas Ménard: Jack and I had been working with replacement animation for a while, mainly through commercials. We had many character heads, and body parts from previous films. For a couple of years, we’d been writing an eight-to-ten-minute short film, but it was ambitious. We felt, if we wanted to improve our replacement animation techniques, it was better to do something shorter first. And so, we came up with the script for Blue Goose.

Jack Cunningham: We had these pieces around us, and we used them as inspirations. We thought, let’s try and make one minute have impact and atmosphere, and give it the time and attention to detail, to show people what we’re capable of outside of the commercial zone.

Did you start by sketching?

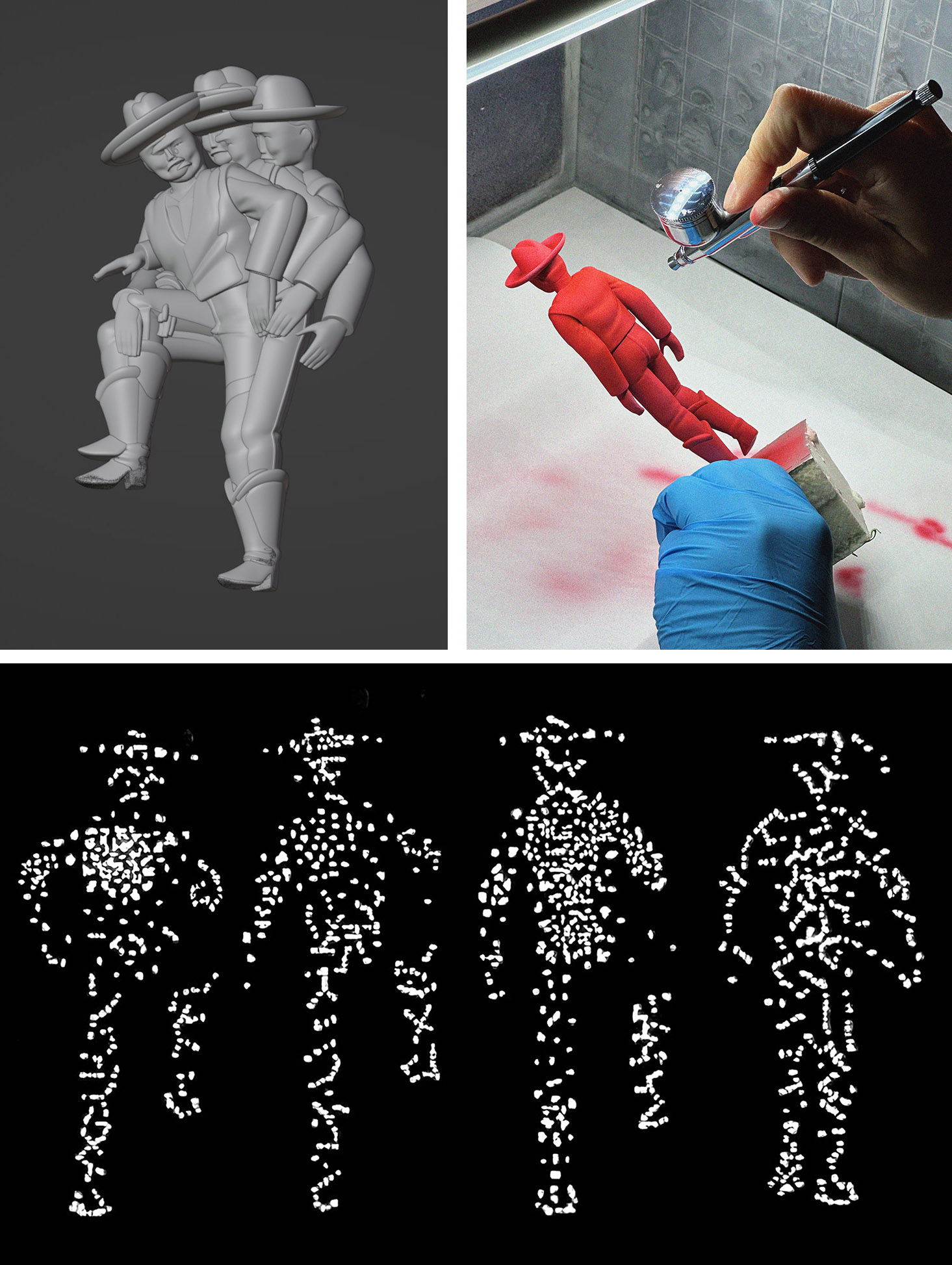

Ménard: Drawing is always the foundation of everything we do. We start on paper, finding interesting compositions with pencil usually starting with the silhouette of a character. With these films, the animatic process was a little bit of a mix. Once we had a pencil-and-paper animatic that functioned, we did more advanced sketches using Blender in grayscale.

Why is the first short, about a red cowboy, called Blue Goose?

Cunningham: I happened to visit an antique shop in San Francisco where I found some vintage advertising labels for peaches [Blue Goose Produce]. That sat on my desk, and it was such an evocative name. When we were tackling this story about the modern world, seen from a 1960s style, and the meanings behind brands, the name seemed to work. We also liked the contrast between words and visuals. There’s a little bit of mystery there.

The cowboy is very Talos-like [from Jason and the Argonauts (1963)]. How did you develop him?

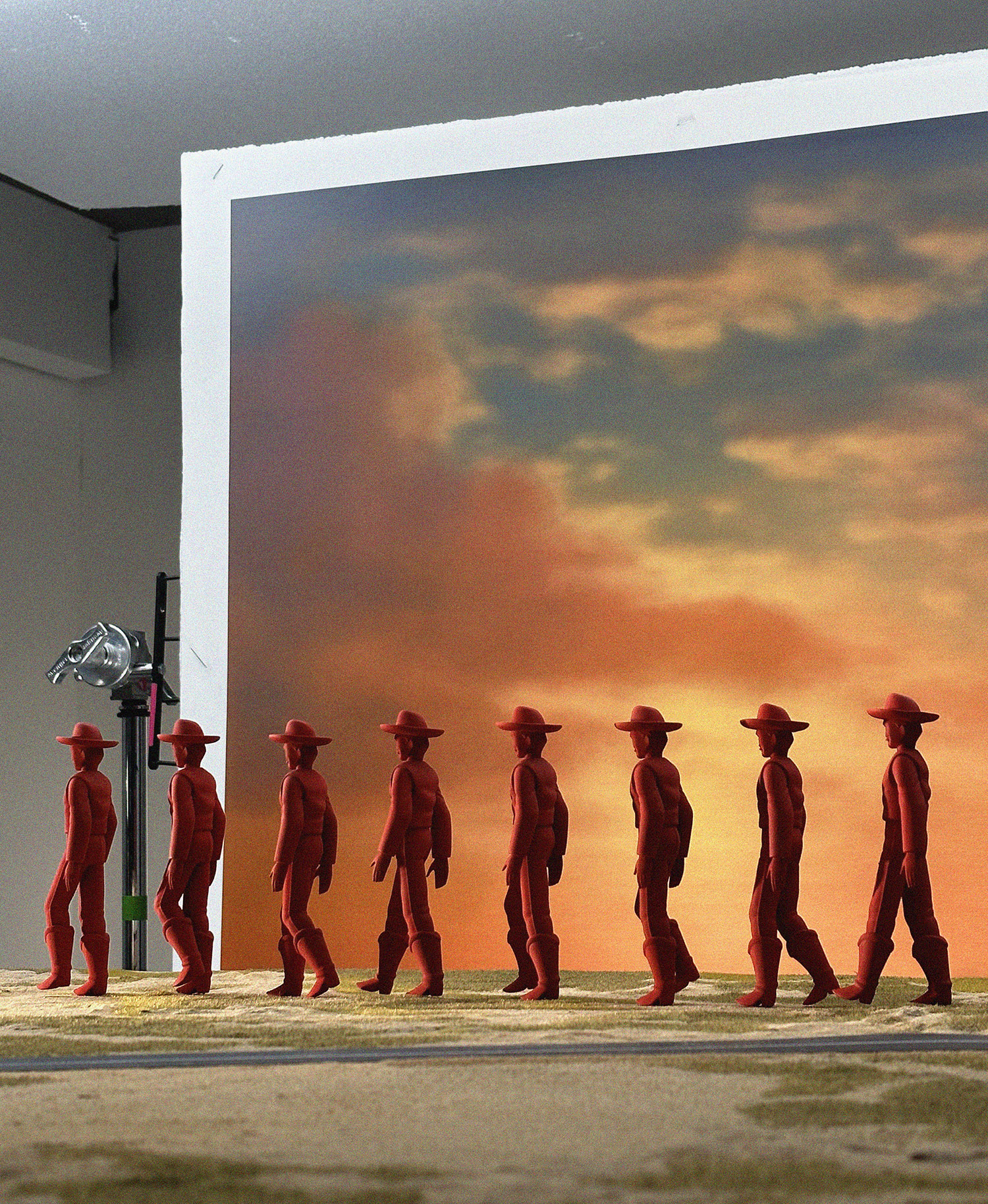

Cunningham: He was 3d printed, and so we wanted to be able to get that motion across in as few frames as possible, to make that movement memorable. That slightly menacing, slow walk with a stuttering frame rate, like a statue creaking to life, worked perfectly. And a nod to Ray Harryhausen is always a charm.

How did you refine the 3d outputs?

Ménard: 3d printing today with resin is very high fidelity. If you look closely, you might see some printing layers, but it’s subtle. And Jack does a really good job at sanding.

Cunningham: The cowboy was my first foray into that. Knowing that he’d be close to camera, and such small figures, I went to town with sanding each model. We also purchased an airbrush, and researched paints to give us a particular matte finish.

Was there any digital rig removal?

Ménard: There’s barely any postproduction. The cowboys each had a pin under their feet, that we pinned into a foam base. The only supports we had to remove in all three films was [in Club Row] for the staircase. That had supports under two pieces of the platform. It was minimal cleanup, and we designed it that way. Our main ‘post’ element was grading, done very generously by Johnny Tully at No. 8 and also at Cheat.

What was your setup for lighting?

Ménard: For each film, we came to our DOP, Ian Forbes, thinking about the atmosphere that we wanted to illustrate the genre that we were shooting. We first set out to do only Blue Goose. After that, we thought, ‘Maybe we should make another…’ It happened that way because it took us a little bit of time to finish music on Blue Goose. There were two, or three months in between each one. Each of them had about three days’ shoot.

What inspired the Escher/Kafka vibe of Club Row?

Ménard: I have an interest in the pictorial space within painting. I find that staircases as a subject are a good way of playing with that. I remember saying to Jack, ‘I want this film to be a spinning staircase.’ We focused on the engineering aspect of how to make that work in stop-motion replacement animation. And then, we added themes to make a story.

Club Row’s opening is sinister. Is that a floppy disk emerging from coffee, like the Lady of the Lake?

Cunningham: I was in Cornwall with my family, near Tintagel, so the Arthurian tales were very much in my head. I suggested to Nicolas, ‘I know we’re doing this Bauhaus staircase with corporate espionage, but let’s put a bit of Arthurian legend in there.’

Where did the title ‘Mythacrylate’ come from?

Cunningham: The chemical name for acrylic is [polymethyl] methacrylate. So, we made the trees out of acrylic, and we added ‘myth’ to give it a ‘mythic’ feel.

How did you animate the swordplay?

Ménard: We had 18 figurines doing a cycle. And then, we redistributed them in the set to create the army. That was an intense day of shooting. Each figure had its number 3d-printed under its foot. We aligned 18 figures at once, and every frame I had to swap their placements, to reposition them, but also try not to make any of the trees move. It was a challenging shoot, but it was the centerpiece of the film. The technique of replacement animation is all about the multiplicity of figurines. So, we found a story that showcased that.

The audio for the series is very atmospheric, and you both have music credits, with Bridget Samuels on the first – is that correct?

Ménard: Yes, Bridget Samuels, our dear friend, did the music on [a] Corona beer commercial [we worked on] back in 2019, and she agreed to do Blue Goose. We were so lucky.

Cunningham: Bridget is a music supervisor with Mika Levi, who had just done [Jonathan Glazer’s 2023 drama] The Zone of Interest. To have Bridget’s talent was great. Something so simple can be so evocative. That kicked off the sound design for all the films. Bridget didn’t have time for the other two, so we had to step up.

Ménard: Jack did Club Row. After that, I gave Mythacrylate a try. Joe Wilkinson, who did the mix, then took what we did, and brought it forward very beautifully.

What is it about this medium that fascinates you?

Cunningham: It’s physical. In the face of AI, and generated imagery, at the end of our process, we’re not just left with an mp4; we have a magical array of puppets and sets. In fact, we had an exhibition where people came to see not only the films, but the sets themselves. One of my friends has a clothing shop at Coal Drops Yards in Kings Cross. It’s a vibrant area and Google’s headquarters are being built around the corner. We were very lucky to have a great space to screen the films and show the work.

Ménard: I also think that replacement animation echoes culture in an interesting way. We love working within that aesthetic of how sculpture is formed, how you can retain the detail and the beauty of each shape in the same way that you have in a sculpture, and then apply that to animation. It’s something that we find interesting.