The Oscar Shortlist Interviews: How To Craft A Story For A Short Film

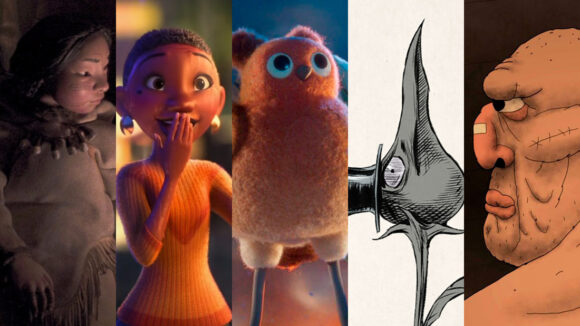

This year, 15 animated shorts — not the usual ten — have been shortlisted for an Oscar.

As we wait to learn the nominees on February 8, we posed the same three questions to all of the shortlisted directors, to learn more about how they made their film and how they view the landscape for shorts today.

We are publishing their answers across three features, of which this is the first.

Our first question:

What is the hardest thing about telling a story in a short runtime, and how did you resolve that challenge with this film?

Joanna Quinn and Les Mills (Affairs of the Art):

The key thing is getting the structure and framework right, initially establishing a very simple synopsis, followed by a tight script, storyboard, and timed animatic. The previous three Beryl films were “single-event” films with simple structures, and they ran from five to ten minutes each. But the timeframe of Affairs of the Art is vast because we are exploring the backstories of the Beryl family and how their lives developed from childhood to middle age, and delving into the familial obsessions and personal eccentricities. Affairs of the Art is a “multi-event” film and could easily have been much longer than 16 minutes, but we prefer the short-form format.

Zacharias Kunuk (Angakusajaujuq: The Shaman’s Apprentice):

In our culture, we don’t talk much of how things are made — we watch and learn. So to make this film, we had the right people who worked on this. Lots of attention had to be paid to make sure the set props and clothing and all the actions were accurate.

Claude Cloutier (Bad Seeds):

The short format determines the kind of story you can tell. The time limitation doesn’t allow viewers to deeply identify with the characters, nor does it allow an overly complex script. I think that despite those constraints, you can still address any subject in an animated short. You simply have to adapt the narration accordingly. This is why animation filmmakers tend to use archetypes or symbolic language and rely on graphic expression to compensate for the short runtimes of their works. In that sense, short-form animation is closer to poetry than to the novel.

Hugo Covarrubias (Bestia):

I think the most difficult thing was trying to condense a timeline that takes place over several years without losing the essence of the premise, and maintaining the intention of exposing the evil that reigned in Chile in one of the darkest decades of our history. Add to that the psychological component of the protagonist. We tried to solve this difficult task through symbolic elements in the scenes, in the actions, in the materiality, and in the scenography. All these elements ended up joining pieces of the story as if they were pieces of porcelain. Not having dialogue imposed a difficulty that we had to face through the gesture in the performances, the actions, the rhythm of the structure of the script, the editing, and the sensations given by the music.

Anton Dyakov (Boxballet):

The challenge isn’t telling a story in a short runtime. Rather, it’s finding the right proportion, the right amount of story to fit that runtime. My criterion for knowing whether we’ve hit that mark is emotional resonance when the curtain lifts. What makes things so difficult is the subjectivity of it all. What resonates with you might not resonate with someone else. Hoping for that miracle, of a visceral response by the viewer to what you’ve created, is at the core of my work and what motivates me.

Sandra Desmazières (Flowing Home):

The most difficult thing is to convey a story with all its issues, to communicate the characters’ states of mind — like listening to a song, immersed in a specific atmosphere. In the span of 15 minutes, Flowing Home recounts the aftermath of the Vietnam War through the eyes of two sisters who are separated for 20 years. Through flashbacks, ellipses, and music, we pick up the sisters’ journeys at various times during the 1970s and through to the 1990s. I provided just enough information to guide the audience and let them be carried along by private moments that the sisters experience and that are etched in their memories, showing the living as well as the dead.

Hugo de Faucompret (Mum Is Pouring Rain):

For me, it is to be able to find the best path to tell it the best way, according to the format we chose. Most of the time, I have more ideas than I could ever put in one single movie. Choosing which idea fits best is a hard thing to do. I often stick with one idea, thinking it must be the one, before realizing sometimes, and after talking with my producers at Laïdak Films or the crew, that it should be the opposite for the sake of the story. I feel that trying to think first in a narrative way always helps a lot to choose what to keep or what to let go. Even if it means that you must give up a wonderful visual shot you really like.

Reza Riahi (The Musician):

My film is very character-driven. I want the audience to connect with the old musician and his beloved. In short films, you don’t have the luxury of time to set up characters and their circumstances, so I had to be very precise: every shot and frame counted in building up this key emotional connection with the audience. I decided to choose an important moment in their lives when, after being separated for 50 years, the musician and his beloved are unexpectedly reunited. The audience sees the story unfold from her perspective.

Erick Oh (Namoo):

Making a short film is like writing a poem, while a feature film is a novel. You just need to connect the right idea to the right medium. Once you understand this and comprehend the strength and weakness of the medium of short films, you’ll know how to fully take advantage of it, rather than being challenged by it. I think it’s more successful when it’s more visual and less dialogue, more poetic and implicit than a clear narrative.

Simone Giampaolo (Only a Child):

Even though we trimmed and re-edited Severn Cullis-Suzuki’s words to make them flow better with the visuals, the overall runtime was mostly dictated by the original speech’s length — circa six minutes — which was easy to respect and control over the production period. [Note: Only a Child sets animation to a speech Cullis-Suzuki delivered at the U.N. Summit in 1992.] The real challenge was making sure that each of the 20 segments, each around 10–15 seconds long, would successfully tell a complete mini-story in a few seconds, and also work in context (next to the surrounding segments).

Mikey Please (Robin Robin):

With so little time to play with, every frame counts. [Co-director Dan Ojari], editor Chris Morrell, producer Danny Gallagher, and I would be trading frames and fiercely arguing our case for each 24th of a second. Our struggle centered on the balance between packing in what was a fairly complex plot for a short, whilst allowing space for comedy and “thinking moments” for characters. We needed the audience to be with Robin on her internal journey and that requires space. But when ten other action-packed sequences are jostling for that space, it was hard to justify the quiet moments when seemingly nothing is happening. But Dan was fantastic at fighting that corner.

Bastien Dubois (Souvenir Souvenir):

I’m quite impatient, and I’m always worried about wasting my audience’s time. So I tend to move quickly, tell my story quickly, edit quickly. A bit too much. With Souvenir Souvenir, I had an issue: the narrative I was drawing inspiration from — my life and relationship with my grandfather — kept going during development and production. So the film almost doubled in length [over time]. Also, I had to cut almost one minute to bring it under 15 minutes, which is the upper limit for some festivals. My edit was already to tight; I really had to force myself.

Weijia Ma (Step Into the River):

At the beginning, I had a longer version of the story with more characters. When I started the scriptwriting, I tried to show every detail. Then I showed it to my producers and my friends, and they got lost sometimes. So I cut things down to focus on the two main characters. I think it’s always good to show it to new people, because I got numb sticking with it for too long. Although I think to prepare more is a good thing. It’s a way to think through the world I built, and make it real.

Zach Parrish (Us Again):

Because the intention of storytelling doesn’t necessarily change depending on the length of the film, the significance of every frame of a short film becomes proportionally more important. For Us Again, every shot had to communicate layers of story and emotional detail. We tried to boil every shot down to its emotional intent and then challenge our choreographers and animators to communicate that intention with only the characters’ bodies. In a way it is about simplification, but hopefully within that process we have allowed the audience to deeply experience something.

Alberto Mielgo (The Windshield Wiper):

Someone said that if you master short storytelling, you will be able to handle any format. But I don’t agree with that. Short storytelling is really challenging because of condensation and synthesis. The audience must feel satisfied with little and that is indeed hard. Here I could bring up the shortest story probably ever, by (or attributed to) Ernest Hemingway, as an example of how a short story with very little information can open so many emotions: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.” The end.

Some answers have been edited for length and clarity.