The Creator Of ‘Courage The Cowardly Dog’ Dissects His New Comedic Horror Short ‘Howl If You Love Me’

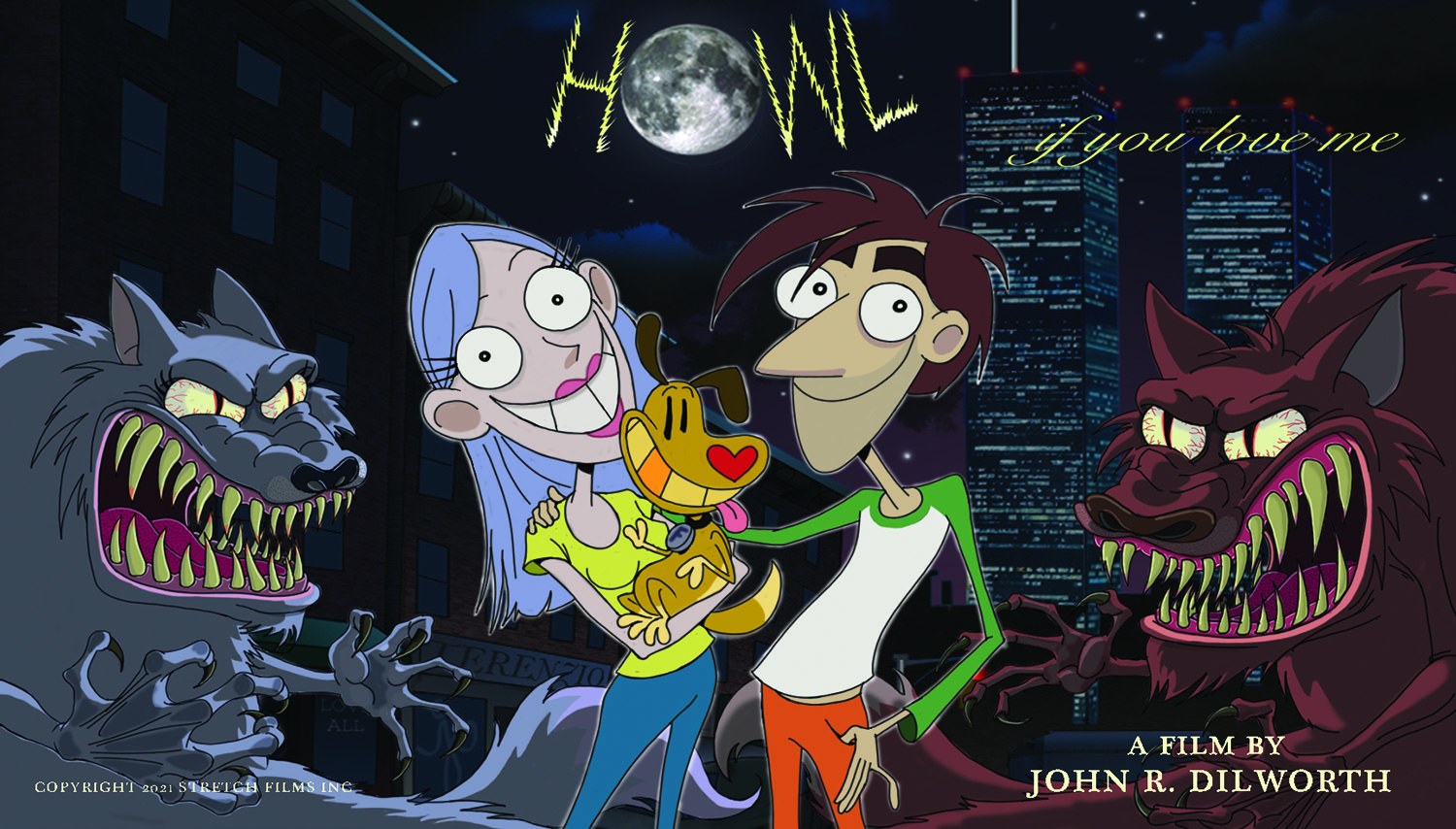

John Dilworth, the creator of Cartoon Network’s classic comedy horror series Courage the Cowardly Dog, has recently unveiled a new short comedy-horror film, Howl If You Love Me. This seven-minute, energetic take on the problems of living with a lycanthropic lover adds another intriguing entry to Dilworth’s eclectic body of work.

Accompanied by Pavel Tsvetanski’s oddly fitting, yet delightfully out-of-place piano score, and showcasing Dilworth’s Tex Avery-inspired animation style, Howl If You Love Me tells the story of Jules and Jim, a couple deeply in love. (The characters’ names are a nod to filmmaker François Truffaut’s 1962 arthouse classic Jules and Jim.)

However, rather than the love-triangle that Truffaut’s film explored, Dilworth’s characters have another complication: Jules is a werewolf. During a full moon, Jim locks Jules away for her safety, but when the authorities arrive at their apartment, Jim is forced to take drastic action, making a profound sacrifice to protect the one he loves.

Speaking with Cartoon Brew, Dilworth shared insights into the film’s genesis, production process, and his enduring passion for storytelling.

Inspiring Howl

After completing his off-the-wall, 22-minute comedy Goose in High Heels (2017), Dilworth sought a project that was more accessible and less unconventional. “In 2019, I wrote a premise exploring the relationships between family, lovers, and friends, and the contrast between who we believe them to be and who they become under stress,” he explains. “It’s astonishing how our loved ones can seem possessed when stress takes hold — and this condition can be contagious. Horror felt like the appropriate genre to express these ideas, but comedy was essential too. Thank Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein for that influence.”

Dilworth initially envisioned his new short as a portrait of young lovers framed by the commercial tropes of traditional romance. However, as the creative process unfolded, his intentions often diverged from the final outcome. “What I intend to occur and what actually occurs are contradictory,” he admits.

New York City’s former World Trade Center twin towers feature prominently in Howl If You Love Me, serving as a metaphor for the duality of relationships. “The towers reflect our lovers and symbolize their fragility and impermanence,” Dilworth explains. “We see how their strength and confidence can easily disintegrate before our eyes.” The film also juxtaposes the Moon and the Sun, symbolizing life’s temporal and timeless elements. “The Moon, ever dying and reborn, parallels Jules disintegrating into a monster and returning, while the Sun embodies the eternal light binding Jules and Jim as lovers — as tightly as any troubadour might sing.”

Horror Themes

Comedy tinged with horror has been a recurring theme throughout Dilworth’s career. He recalls a deeply personal moment: “I remember when my kid brother slipped out of the room and my mother and I were holding his expired body in the hospital, and we began laughing violently. This is an example. The expression of our grief took this form. How absurd and ridiculous it was, to have life happen and me only a witness!” Dilworth reflects on how, whether through laughter or despair, energy is released. “The passion is to eject the energy of all my grief up and down the line.”

In his animation, he intentionally counters the frightening with the comical, embracing a duality, a contradiction he sees throughout life: “I wish to soften the edges of the unrelenting rigor and sorrow of our world — the impotence — so as to avoid suggesting that a dominant force overwhelms love.” In Howl, Dilworth illustrates this through Jules and Jim, who become violent to ensure their love endures. “That particular love and the violence are equal parts frightening and ridiculous,” he notes.

Dilworth believes that comedy and horror are essential elements of humanity. “I have a doctrine,” he states, “that humanity needs three qualities if we are to make it out alive: possessive love, horror, and courage. To me, all three require being able to laugh at ourselves, not holding on too tightly. We need a zeal to move forward, horror to teach us how we wish to live with one another, and courage to suffer nobly.”

Reflecting on Howl, Dilworth describes it as a romantic comedy with horror: “I have been fortunate to know the joys and sorrows of being in love. I like being ‘in love.’ Jules and Jim are lovers, doomed yet ever joyful for the living knowledge of the temporal and timeless elements of life.”

Documenting Howl

The production of Howl If You Love Me was meticulously documented in more than 200 YouTube videos, a practice that originated during the creation of Goose in High Heels. Dilworth explains: “I was producing that film at a residency in Uruguay. I was so far from home, and the insects were so very large and formidable. A way to feel less unnerved and stay in touch was recording the daily progression of the work.”

He continued this practice with Howl, transforming the videos into a tutorial on animation: “I documented the entire production, from the writing of the premise, through storyboarding, pre-production, and animation processes. I started on paper, then switched to Toon Boom one minute into production,” he adds. The videos also covered music, sound design, and mixing, followed by a review of how the short was received at festivals. Beyond showcasing the making of Howl, the videos also included Dilworth’s personal feelings and experiences at the time, functioning as a video journal.

Although Dilworth seems to be shifting from traditional festival films toward more genre-oriented ones, he remains uncertain of his work’s current marketplace viability. “I never felt that I had a commercial touch,” he reflects. “I’ve been unconcerned with practical and material considerations. I do enjoy when larger audiences relate to my animation, but I don’t have a formula. I feel I would make a worse mess of a work if I planned on making a ‘universally’ relatable piece.”

Instead, Dilworth trusts his instincts, letting his internal drive shape his creations: “I follow my organs and whatever most compels me to expression.” He notes that his most popular shorts – The Dirdy Birdy (1994), The Chicken from Outer Space (1996), and Life in Transition (2005) – were all surprises. He explains: “The relative success of these works is unrelated to any genre but stems from a shared experience.”

That said, Howl has performed well at horror festivals, while traditional festivals, in Dilworth’s words, “have overwhelmingly declined it.” Nine months into submitting, he focused on festivals more attuned to the short film’s gothic themes. “Surprise! I made a horror short I did not intend,” he quips.

Animation and Independence

Dilworth has been part of the animation scene for nearly 40 years, witnessing numerous changes in the industry, some for the better, some for the worse. “The Dirdy Birdy was the last short I shot on 35mm film,” he recalls. “Today, the tools have changed. I have not been concerned with the market, and thus my independence — and my lack. Howl was made using computer software for practical and economic expediency.”

Despite the advantages of technological advances, he remains cautious about the industry’s increasing homogenization. He parlayed these concerns into the dilemma facing the protagonist of Howl.

“For Jim,” he says, “turning into a werewolf to safeguard against loneliness would be a big change. Do you think the market is more and more homogenizing sentiments, suggesting how we should feel, think, and experience our unique lives? It may be stunting our spiritual discovery of ourselves directly.” Dilworth, however, sees hope in independent animation: “I see fewer dominating forces in the indie sphere, where the expression to eject is very much personal and inviting to those still tuned into their aesthetic prejudices.”

The Legacy of Courage

After more than two decades, Cartoon Network’s series Courage the Cowardly Dog remains Dilworth’s most iconic work, a testament to his creative principles. “The continued popularity of Courage,” he reflects, “affirms my three principles stated above, and of that, I am not surprised.” For Dilworth, Courage embodies humanity’s resilience against forces that seek to strip away what makes us human.

Dilworth draws parallels between this theme and the dualism explored in Howl: “The supernatural phenomena of human beliefs in werewolves, for instance, are being eclipsed by technology. I include technology in Howl as another dualism between the organic and the synthetic, and its suggested dialectic. Technology has no emotion. Courage has emotion. He is afraid. Technology is not afraid. How would a world be if humans became more like technology? What would be the value of turning into a werewolf? There would be no need for Courage.”

As for new episodes of Courage, he admits that network interest has waned: “I had wanted to make a fifth season back in 2002, but there was no network will. The system was changing. In the past, we’ve been invited to do holiday specials, which I began writing, and those got reversed. We even produced a cg Courage pilot funded by Turner in Hong Kong, but that got the kibosh from Hollywood. The prequel suffered similarly. There isn’t any network will to make new episodes, and there it is — until it isn’t. That’s showbiz. It’s living Las Vegas.”

Meanwhile, he has written a feature-length script based on Howl, though he doesn’t rule out the idea of a series. “A series could also be attractive,” he says, “if I could come up with a formula, of course.”