Oscar Focus: Amanda Forbis and Wendy Tilby Talk “Wild Life”

BREWMASTERS NOTE: This week Cartoon Brew takes a look at the five Academy Award nominated animated shorts. Each day at 10am EST/7am PST we will post an exclusive interview with the director(s) of one of the films. Today, we discuss Wild Life with its writer/directors Amanda Forbis and Wendy Tilby:

Chris Arrant: This story centers around the concept of a remittance man, something most people don’t know about, but was pretty common in North America a few centuries ago. It sounds like a great historical fact, but what made it something you thought relevant and interesting to you two and to today’s audiences?

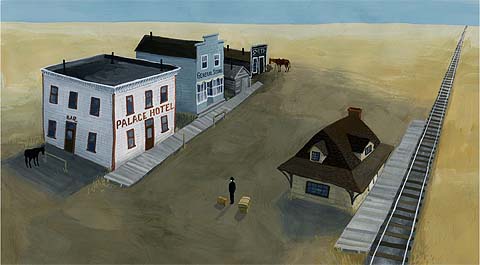

Wendy Tilby: We Canadians tend to think our national history is quite boring. One almost forgotten historical phenomenon was around the turn of the 20th century when thousands of these remittance men flooded into western Canada, sent by their well-to-do families because they were essentially useless. Britain was becoming a meritocracy and so these second sons could no longer expect to land positions just because they were members of the aristocracy. They tended to have a pretty good time….until the reality of surviving in the Canadian wilderness caught up with them.

We were also attracted to the idea of Empire and how education and breeding doesn’t prepare one for surviving in the very harsh conditions. The remittance men were victims of all that fine breeding and pressure from their families. But they also relished the escape and the adventure, and the dream of being cowboys.

Amanda Forbis: I don’t think we contemplated necessarily if it would be relevant to today’s audiences. I think sometimes you just find these things interesting even though you can’t nail down why exactly. But overall, there’s something inherently poignant about colorful characters inhabiting a bleak landscape.

Wendy: The other part of it is that both Amanda and I have English grandparents who came to Canada around that time and experienced similar hardships.

Chris: Were you able to talk to your grandparents about the story inside Wild Life to get their first-hand viewpoint on remittance men?

Amanda: Unfortunately my grandparents are long dead, but I had my mother’s story of hardship on the farm to go by. And that seeped into my bones and became part of me. Wendy knew her grandparents, but they’re long gone as well.

Wendy: My father is still here and he’s told me stories of growing up on a farm just west of Edmonton during the Depression. It was very grueling.

Chris: For the animation, I’ve read you used computers for the initial part of the animation but then traditionally painted the scenes on top of that, which I’m sure took a considerable amount of time. Was that the plan from the beginning, and how did you come to know that you could only do so much on the computer for animating this story?

Amanda: Actually, we had hoped to do Wild Life entirely in the computer because we thought it would save us time. But it became a challenge. We were never able to arrive at a look that did the Alberta landscape justice.

Real paint is more visceral. There is a randomness we like that is very hard to replicate in the computer. When trying to replicate randomness on the computer it starts to become idiotic, but in real painting it’s tactile and fun. If you’re going to spend so much time on one project, you might as well enjoy it. But it was insane, I have to admit. When we were heading in to do the sound mixing, Wendy wanted to print out buttons that said “Never Again”.

Chris: Your film really gets across the landscape and atmosphere of Alberta. You’re both from Western Canada, so how did growing up and being able to create this so close to the province help you accurately portray it without mythologizing it?

Wendy: Probably because Canadians tend to be understated, we tend not to mythologize. Canada has always been between two empires — the British and the American – and we thought it would be interesting to do a Canadian version of an American western that hinted at the difference between our two histories. Culturally speaking, Canada was much tamer due to the fact that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police arrived before most settlers.

Amanda: The environment was a big factor, but a few of the remittance men did stay and survive, and as a result Calgary and a lot of Alberta has remnants from that time.

Chris: In both this film and your earlier short When The Day Breaks, the writing of letters plays a huge part. As storytellers and animation artists, why has correspondence become such a key role in the message you’re trying to get across?

Amanda: In When The Day Breaks there isn’t a letter so much as a shopping list. I guess it’s just part of the stuff that churns out of your brain that gives those two pieces commonality we don’t recognize until later.

Once the two short films were finished, we looked back and saw a number of similarities. For instance, the two scenes in Wild Life of the feet in the snow is a parallel to the way we use the toaster in When The Day Breaks. Also the pan around the empty room at the end in Wild Life compares to the pan around the chicken’s empty apartment at the end of When The Day Breaks.

Wendy: In fact, the characters of the pig and the remittance man aren’t that dissimilar; naive and optimistic – forced to come to terms with an alarming reality.

Chris: I wanted to ask you about the comet metaphor. That’s a really unique choice to describe the British visitors as comets. How’d you come up with that, and was it part of your idea from the beginning or did it only develop later on in the story process?

Wendy: The comet was a notion we had at the beginning of the project when writing the script. We were looking at current events of 1910 with the idea of glimpsing the goings on in Europe while our character is in the middle of nowhere – civilization vs wilderness. When we came across Halley’s Comet, we started to read about comets and found them to be an apt metaphor for the character himself. Also, when he sees the comet at the end, it is a kind of religious experience for him – a way to go home.

Astronomy and natural history were popular subjects at the turn of the century. In the scene where he’s rowing in the pond, it’s Darwin he’s quoting – he’s musing about natural selection and not realizing that his own chances of survival are no better than the gnat’s.

Chris: Canada is one of the leading countries when it comes to immigration per capita. Was modern immigration in your mind as you were making this film? And was there any intention to show the difficulties and culture shock that contemporary immigrants to the country might face?

Amanda: Well, I certainly have sympathy for immigrants new to our country, especially those coming from a more temperate place with a very different culture. I wonder how they can do it; to make that much of an adjustment? I ask that because I don’t know, rightly or wrongly, if I would be able to make those adjustments myself. In that way, yes we did think about that.

I think, more than that though, it goes to a more basic question of adaptation. That’s why we inserted Darwin and the notion of ‘Survival of the Fittest;’ that notion of what happens to us when presented with a situation beyond our coping skills and our acquired knowledge. A friend of ours brought up Robert Falcon Scott, the explorer who set out to be the first to make it to the South Pole but was beat by the Norway’s Roald Amundsen and died on his return voyage. There’s a great book called Last Place On Earth describing Scott’s journey. In reading it you can’t help but compare Scott – who did not adapt – and Amundsen – who did – and wonder who you would be most like in those circumstances.

In our modern world we have occupations that are so specialized like investment bankers or animators like us, anybody working in the modern world wouldn’t fare well if tossed out on the prairie. The Ukranian woman in Wild Life does make it and one has to look at why she survived while our main character did not.

.png)