It’s Not Just A Rubber Band, It’s An Animated Character

In a world where perfection and shininess become easier to attain, uniqueness and imperfection are increasingly appreciated. Through three animated shorts, this thematic piece explores the storytelling power that real-life materials possess.

Together with the films’ directors (through phone and Skype interviews) Cartoon Brew analyzed the workings of the witty A Girl Named Elastika, the emotional Women’s Letters, and the irresistibly cute yet cruel Fantaisie in Bubblewrap. Push pins, papier-mâché, and bubble wrap — these materials have been integral to these films’ storytelling.

Grand adventures with small objects

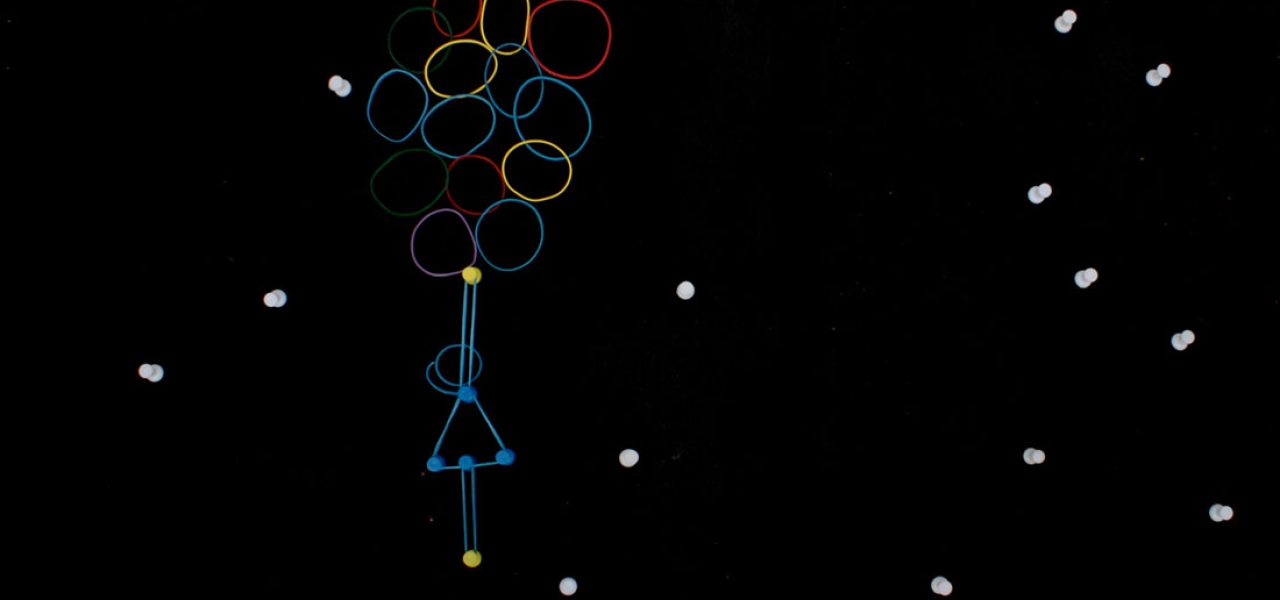

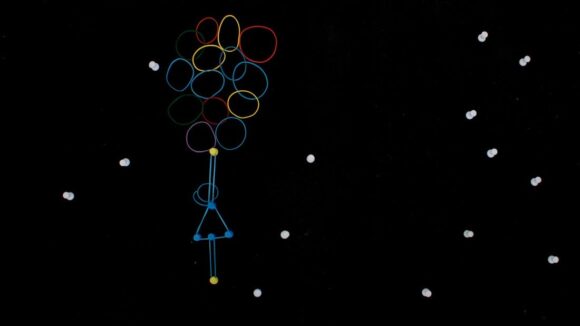

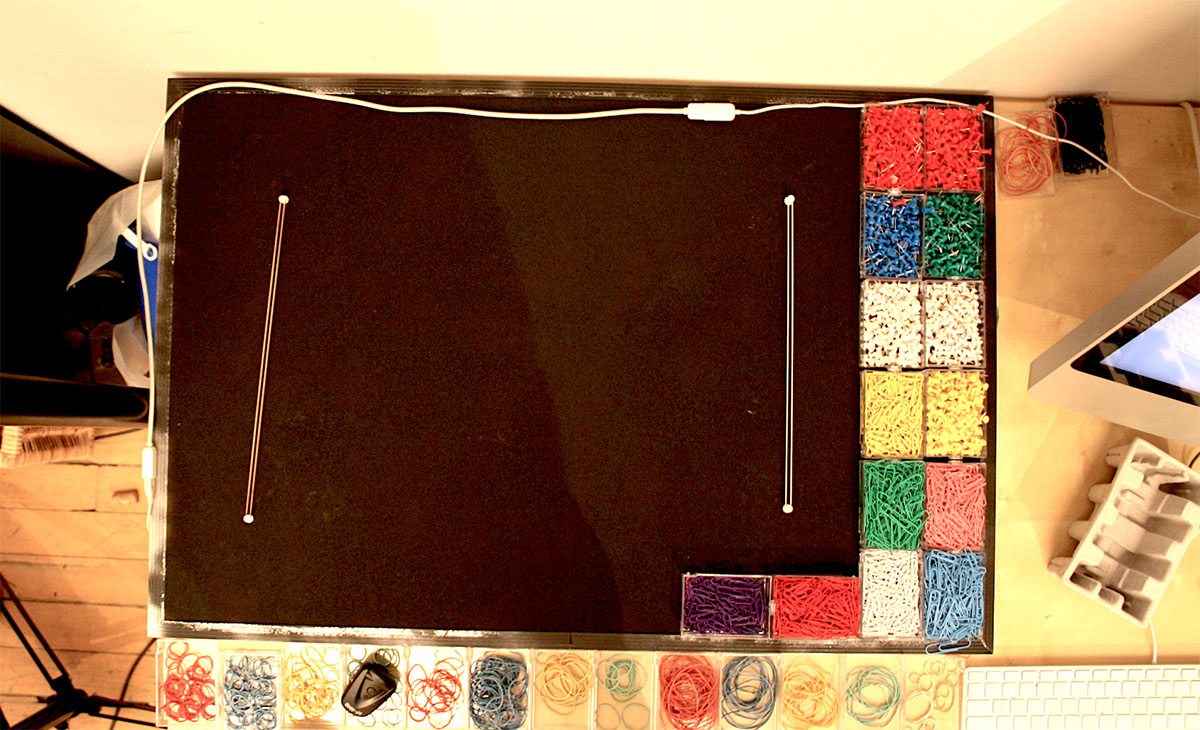

In Guillaume Blanchet’s A Girl Named Elastika, main character Elastika is portrayed by no more than a set of push pins. She travels through the city, the pyramids, the ocean — fantastical worlds built up from nothing more than rubber bands, push pins, paper clips, cork, and paper. Sometimes Elastika takes shape more or less like a recognizable character, through a group of push pins, but there are also many times that she’s far away and basically just a dot.

“With this film I challenged myself to make viewers feel for small, puny objects,” Blanchet explains. “I love it when people see so much in her as a character, or even as a representative of girl power. When the viewers start to think of a push pin as a person, when they’re at a point where they feel scared, happy, or excited for it, then I’ve succeeded.”

Throughout the film, Blanchet keeps reminding viewers of the realness of the materials by incorporating many close-ups and making some visual sacrifices. “The raw color of the cork isn’t really attractive visually,” Blanchet acknowledges, “but at least people will see it’s real.” Staying true to real materials meant no post-production at all, turning the animation into a time-consuming process. Unfortunately some online viewers couldn’t appreciate the effort, commenting things like ‘Get a job’ or ‘Get a girlfriend.’ But Blanchet smiles when he reflects: “These people only see the work — not the imagination.”

More often than not, the restrictions the director set up for himself resulted in original inventions. The balloons at the end of the film, for example, are really just a bunch of rubber bands put together. Despite this simplicity, or perhaps because of it, it’s one of the most fantastical and visually sublime shots. “Numerous people told me, ‘This is so simple I could’ve thought of it myself’,” the director recalls. “In my mind that’s actually the best response I could ask for. I love that Elastika is an idea that everybody can have and make.”

War stories told through paper

Women’s Letters is a poignant 11-minute short made out of papier-mâché. It follows a soldier in World War I delivering his comrades letters from their families. The great amounts of love that the letters express heal the soldiers’ scars — physically, since both the soldiers and the letters are made of paper, but also psychologically. The film’s metaphor is painful and beautiful.

While the ideas for the story and form of Women’s Letters were conceived separately, director Augusto Zanovello couldn’t unsee the combination after they connected in his head. “The metaphor is a little obvious,” the director says. “Paper is fragile. You can burn it, you can cut it, you can write memories on it, and you can lose a piece of paper very quickly. For me, the human being is like paper. The soldiers in Womens’ Letters embody this paradox; the form is the story.”

The papier-mâché technique also gives the harsh story a certain softness. “War is a painful subject matter that quickly becomes shocking in a realistic style,” Zanovello says. “For this film, I wanted to bring the story into another dimension — a more tender one than reality.”

Any imperfections that came with the hard to manipulate material were embraced by the director. He zooms in on the soldiers’ crumpled paper faces quite often, to intensify emotional moments. “I love visual imperfections. Similar to papier-mâché, life is not very constructed. Imperfection — that’s us. It’s what makes us human.”

Cruel tales on bubble wrap

Arthur Metcalf’s Fantaisie in Bubblewrap will surely leave you feeling guilty about ever popping one of those plastic sheets of bubbles. “A producer friend of mine would do it all the time,” Metcalf says. “She wouldn’t simply pop them though — she’d put a face on each of them first. I thought it was a great idea and asked her if I could use it for a film.”

The film’s cinematographic quality is low, or ‘shitty’ in the director’s own words, but this imperfection might actually contribute to its humor. Different from the previously discussed films though, for Metcalf it wasn’t a conscious choice — while making the film he simply never considered a fancier look or technique. “I just sort of stumbled onto this technique with my then-really-limited skills out of necessity. Animating it in cg or even using a better camera to record with was never a thing. But I think when there’s great jokes, nobody cares about the quality — just look at South Park.”

Regarding the film’s success, Metcalf thinks people enjoy the film because basically everybody is guilty of popping bubble wrap: “The common sentiment in Youtube’s comment section seems to be, ‘I will never look at bubble wrap the same way again.’ There’s that recognition there. In that sense, I do think the actual material, as opposed to a drawn or cg representation, helps the connection in the end. Some people even said they cried at the end — people crying about a bubble-wrap baby. That makes me happy.”

This article is inspired by the thematic program ‘Things Have Feelings Too,’ which was presented at the 2015 KLIK Amsterdam Animation Festival.