Interview: John Morena Explains How He Made One Film Per Week For A Year

In 2016, John Morena came to a realization. He was approaching 40, and although he had a successful career as a commercial animator, he was dissatisfied. His attempts over the years to develop a film of his own had come to nothing. His ambitions as an artist remained unrealized.

This “come-to-Jesus moment,” as he describes it, led Morena to resurrect an old idea. Every week for a year, he would make a very short animated film, with a view to exploring unusual animation and vfx techniques that he might then use in his commissioned work. He would upload them to Instagram, which restricted each film to a maximum 60-second runtime. Morena wrote a manifesto setting out his principles, then hunkered down in his New York home and got to work.

A year later, Area 52 — as the project came to be known — was complete. Not only had the challenge given him a new sense of fulfillment, Morena found that the films were interesting in their own right. He started submitting his favorite ones to festivals, successfully: they were picked to play at Annecy, Hiroshima, Ottawa, and Anima Mundi, among others. Morena may be the only filmmaker ever to have had six films playing simultaneously in competition at Annecy.

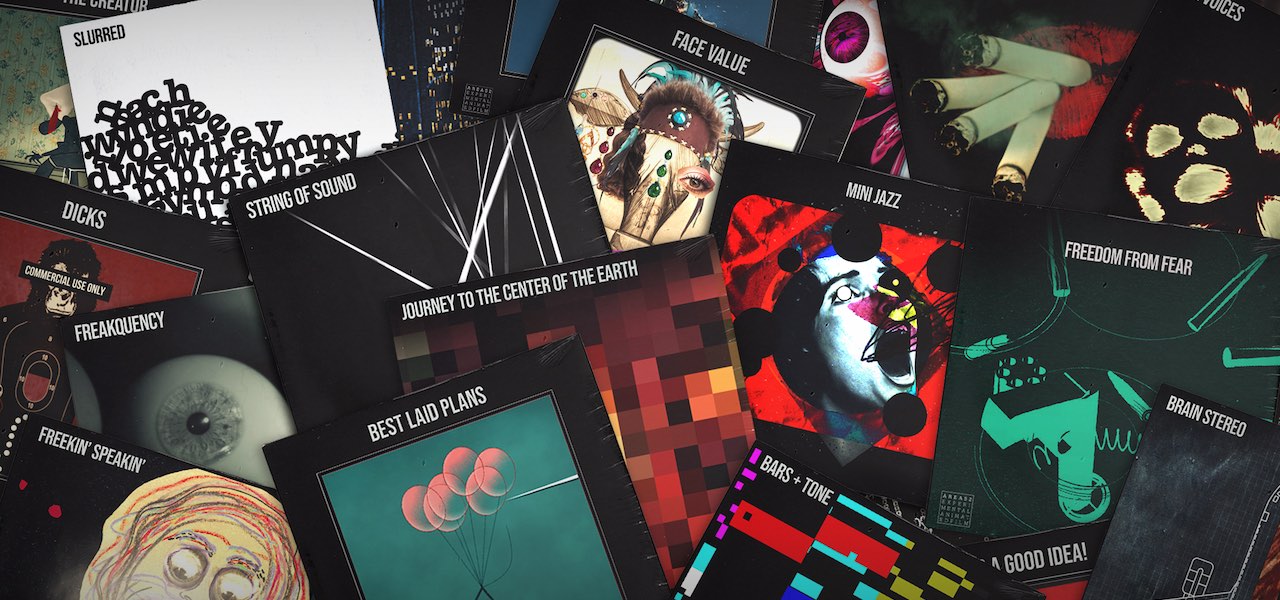

On the festival circuit, these works drew the attention of the distinguished distributor Autour de Minuit, which released 25 of them — the Area 52 “A-Sides” — on Youtube this week. They make for a striking collection, ranging across all kinds of techniques: cut out, pixilation, digital illustration, etc. Nuggets of fierce social commentary alternate with abstract experiments in motion. As a rule, they broadly avoid dialogue.

Cartoon Brew spoke to Morena about his creative process, the relative merits of Instagram and Youtube, and the reason he lost a bunch of clients along the way.

Cartoon Brew: How long did you spend making each film, and how did you fit them around your commercial work?

John Morena: On average, they took about three or four days. Fitting them around commissioned work was a matter of placing my personal work as the number one priority. Instead of creating a schedule for making the films based on my commercial jobs, I did the complete opposite and arranged my regular work time around the films. Easier said than done. That required saying “no” to a lot of jobs and losing some clients. It required a big perspective shift in my attitude towards work.

The sound — which, in general, you designed — is central to these films. Did you create sound and images in tandem?

Morena: It varied. Films like String of Sound and Face Value required a pre-cut audio track for me to animate against. Other ones, like Home: A Portrait of New York City, were animated in pieces with no sound, put together in an edit, and the sound design was done last.

You gave up on some films midway through. How did you know when one wasn’t worth finishing?

Morena: When it felt forced. Most times a good solution to that was to go in a completely radical direction from the original concept. But sometimes that didn’t work so I had to throw it out completely and come up with something else.

Did you ever feel that the format was limiting your creativity?

Morena: No, quite the opposite. Limitations like this are where the magic happens and 60 seconds can be a lot of real estate for a film if you use it wisely. I was able to be concise and very clear about what I wanted to say and could present it more like a news headline as opposed to the entire article. I always encourage other filmmakers, especially young filmmakers, to place limitations on themselves and to keep it as simple as possible.

Did you study similar projects — say, Greg McLeod’s 365, for which he animated one second per day for a year?

Morena: I’ve seen 365, which is an astonishing feat of dedication, but I tried not to be influenced by other films. I did a lot of reading. I also watched a lot of archival interviews with artists I respect. Also, getting out of the house as much as possible and observing the world with a heightened sense of awareness helped out a lot.

I tried to cannibalize as many things as I could and use them as conceptual inspiration. I like to make films that express my worldview. So I’m more focused on honing in on what I want to say as clearly and succinctly as possible, and just use the physical act of filmmaking as more of a playground. I let mistakes and surprises happen and lots of times they were for the best.

You’ve said that the series is essentially about how we’re all animals, and act accordingly. Did that theme emerge during the project, or did you set out with it in mind?

Morena: Definitely set out with that in mind and it was the crux of most of the project. Some of the films are just purely experimental and don’t include this layer of commentary, but most of them do.

Did anything surprise you about the way the films were received on Instagram?

Morena: Yeah — one really great side effect was realizing that the commitment to the goal was contagious to others. I’ve gotten countless messages and emails from random strangers who expressed that they were inspired to go and do the thing they’ve always wanted to do.

How did you choose which films to submit to festivals, and which to present as part of this collection with Autour de Minuit?

Morena: I selected the ones I thought were the strongest, and ended up with a list of 29. Three of those films were put together into one film called Home: A Portrait of New York City, and another two were put together into one film called Slurred. It’s interesting to note that the individual films that make up these two longer films didn’t perform that well on their own. But when put together, suddenly they were premiering at Annecy. It’s crazy how changing the resonance of something can alter its success.

Anyway, putting those films together into longer films got the list down to 26. Those 26 films were submitted to all of the festivals I could find that didn’t have a submission fee. Turns out, all of the best animation festivals in the world are free to submit to, so I lucked out.

As for Autour de Minuit, they contacted me right after the 2018 Annecy selections were announced and asked to view the six films I had in competition. After seeing those six films, they asked to see all 52. I ended up showing them the 26 films that I’d been submitting to festivals and they said they wanted to distribute all of them. They’re also a really good bunch of people to work with so it’s a blessing all around. (Editor’s note: Autour de Minuit released only 25 films in the package because music rights for distribution couldn’t be secured for one of the shorts.)

What do the films gain from this more conventional exhibition route, outside Instagram?

Morena: Well, the three main platforms for Area 52 are all really different from one another. On Instagram, they were sort of a novelty. Filmmakers usually post a snippet of a longer piece, then direct you to the link in their profile to see the whole thing. Other than Area 52, there was a comedy show with puppets called Blark and Son that was also posting episodes that were short enough to be seen, in full, right in the Instagram feed. There weren’t any others that I knew of at the time.

Festival screenings are a world apart. I didn’t have that wide of a reach on Instagram so the festivals offered more people watching the films and everyone watching at once. You can be present for audience reactions. The major competition screenings come along with an air of prestige and there’s a big buzz in the room. You get to actually meet the people who just saw your work and meet the other filmmakers who just screened with you. You get to do a Q&A session and use your words as an extension of your work in front of an audience. You just can’t get those things anywhere else.

I’ve been avoiding Youtube, honestly. The comments section can turn into a cesspool very quickly. It’s a place where the #selfie mentality rules. The one thing I do love about Youtube is that you can monetize your work and make it available at no cost to your audience. I really want to make my films available to watch for free. So, until Vimeo decides to offer monetizing features for filmmakers without asking the audience to pay for it, it has to be Youtube. We’ll see what happens.

The series was originally conceived as a testing ground for techniques you could use in other projects. Have you discovered any techniques you’re keen to reuse?

Morena: I didn’t have the luxury of time to really hone any particular technique so they just are what they are. As long as a new film calls for a technique I’ve already used, I’d definitely try it again. But I don’t want to force it. I’d rather improvise, experiment, and come up with new things.

What are you making next?

Morena: I’m working on a new project called The King of Spades. It’s another collection of tongue-in-cheek animated short films. When people get their fortune told using a regular deck of cards, the king of spades is the most powerful card in the deck. So, the overarching theme for this project is mechanisms of power and control in the modern world.

I want to do it in such a way where I can string all of the shorts together into one longer piece, roughly 45 minutes in length, so an audience can see it as a feature film. Or you can just watch one of the individual shorts, and it wouldn’t necessarily require the context of the rest of it in order to still work.

You can watch all the shorts in the “Area 52 ‘A-Sides'” collection on Youtube. For more information on how Morena made each film, head to his blog.

Some of the answers in this interview have been edited for length.