Gísli Darri Halldórsson on ‘Yes-People’ (Oscar Shorts Interview Series)

Today, we wrap up our series of interview with directors of this season’s Oscar-nominated animated shorts by speaking with Gísli Darri Halldórsson, director of Yes-People.

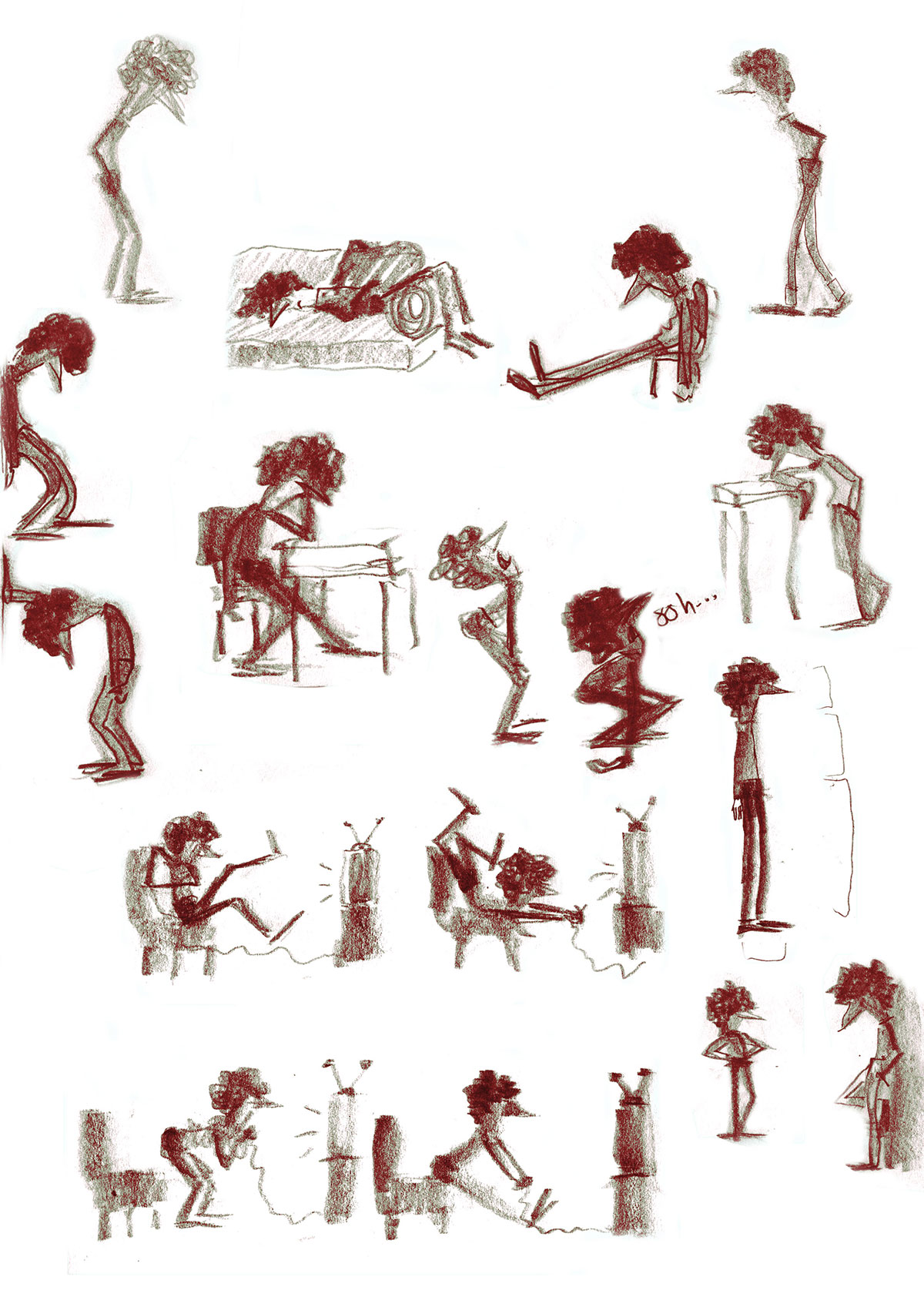

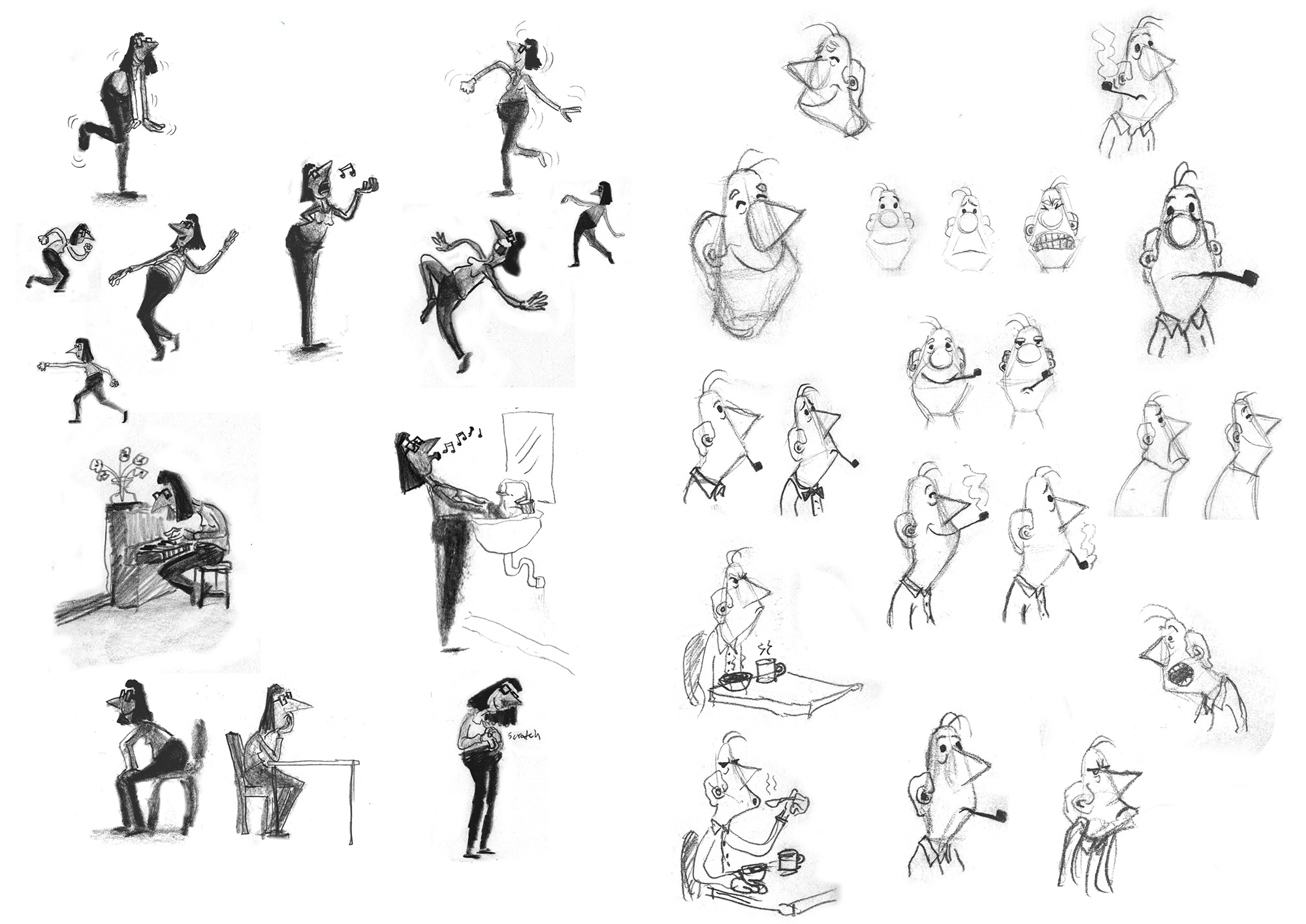

The Oscars’ glitter-gold light has shone favorably on indie animated shorts this year: several nominees in the category have an experimental bent and no affiliation to big studios. Take Yes-People, a passion project by Icelandic animator Halldórsson, which sketches the mundane lives of an apartment block’s inhabitants using just one word of dialogue: “já,” which can be (imperfectly) translated as “yes.”

Across a succession of vignettes, a half-dozen characters go through the motions at home, school, and work; the infinite modulations of how they say “já” hint at how they feel inside. In its wry, laconic portrayal of the joys, tensions, and disappointments underlying people’s daily routines, Yes-People plays like a slightly sunnier version of Anna Mantzaris’s festival darling Enough, or a homage to a Roy Andersson feature.

Much like fellow nominee Erick Oh, Halldórsson worked on-and-off on the project between industry jobs, which have included stints at Cartoon Network and Blue Zoo in London. He eventually teamed up with Caoz, a 3d animation studio in Reykjavík, Iceland, to produce the film. High-concept and comic, Yes-People stood out in the pool of the near-100 shorts that qualified for this year’s Oscar. I’m not surprised it has made it this far.

I caught up with Halldórsson to discuss the film’s shoestring production, Icelandic people’s self-image, and the beguiling power of a single syllable …

Cartoon Brew: When did you conceive the film? Was the idea of only using “já” there from the start, or did it come to you later?

Gísli Darri Halldórsson: The first seed was in 2012 in a conversation with my Irish friends about the word “já” and its multi-tonal meanings. It sparked an interest in me — the idea of a semi-silent film. It was not a film idea at that stage and I didn’t start writing a script until I saw the potential to merge it with my then-obsessive thoughts about routines and habits. So it became a story about people being stuck in a loop with only one word to say.

How long did the production take and how did you finance it?

I started writing and designing in 2013, and up until 2018 it had very much been a stop-and-start affair. I had to find tiny pockets of time in between freelance jobs to work on it. Luckily I got Caoz onboard to help me apply for a production grant from the Icelandic Film Fund. We were successful, but had to make do with about a quarter of our ideal budget.

How easy was it to decide how many characters to include and how long to make the film?

I knew I wanted to avoid a story with a single protagonist. I was very keen to pursue a narrative about a range of people in a mosaic story structure. The idea was to have routines and habits at the center, and have each character reflect a different side of the subject (negative or positive).

I remember using the idea of white light as representing people. Thinking that when you refract light you get the spectrum of colors. I went for the three primary light colors — red, green, and blue — to keep it simpler; this idea is also reflected in the “Já-Fólkið” [Yes-People] logo at the start. Each apartment represented one primary color.

This was also a practical decision, and I found inspiration from another [live-action] silent film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, to use color to differentiate between stories. I also knew I would need each apartment to contain a couple to have some level of conflict. So it was not exactly easy to decide on six characters, but it evolved naturally.

All of the characters are based on several people I’ve known or sometimes combinations of people. The length of the film just came out of the writing and storyboarding process.

What techniques did you use? The backgrounds look almost photographic at times.

Yes, indeed. The photographs come from my father’s massive personal photographic archive that he has been scanning for years now. The characters were cgi and composited into the photos via After Effects. Cgi was mostly a practical choice to match the lens and lighting in the original photographs.

I animated on twos because I feel that this technique has more presence, and a timeless quality which is so hard to achieve in cgi on a low budget. I also desaturated the photos and recolored them just to help them look a bit less “photography.”

I believe the film was partly inspired by a book you read. What was the book about?

Yes! I was reading it during a trip to Australia in 2013 and I can’t find it anymore. It was a compilation that a reporter had gathered about the routines and habits of scientists, politicians, and artists from all over history.

You’ve said that “Icelanders are often nicknamed ‘yes-people’ by our neighbors in Faroe Islands because of how frequently we say ‘yes.'” Is this something Icelanders recognize in themselves? Does that word “já” have a wider range of uses than “yes” in English?

Icelanders are very aware of this, yes. From having lived many years in Ireland and England, I can safely say the Icelandic “já” is used in a much wider context than the “yes.”

I did edit out a few “já” interactions simply because they are too bizarre for non-Icelandic speakers. For instance, Icelanders will often reply “já já” to a suggestion when they actually mean “I’d rather not.” There are probably a couple of scenarios in the film that go way over people’s heads who don’t speak Icelandic.

Tell me about the song that recurs throughout the film. It almost sounds like the singer is singing “já” over the end credits.

The song is called “Sveitin Milli Sanda” and was commissioned in the 1960s for an Icelandic documentary of the same name. The composer, Magnús Blöndal Jóhannsson, wrote the song specifically with the singer, Elly Vilhjálms, in mind. It seemed like a perfect fit for my film, as the singer gives incredible emotional range to one syllable: “ah.” As a lyric on paper, “ah” is completely meaningless, yet the song has so much to say. But you can’t always put your finger on what it is. Just magical.

Yes-People spent much of its festival run playing in virtual festivals. Do you regret this? Did it bring any advantages?

I don’t regret submitting the film during Covid era — I had to get it out after all these years — but yes, it has been really unfortunate and kind of painful. I was looking forward to watching the film with an audience, and I did get the chance at the Reykjavík International Film Festival, which was a really lovely and positive experience.

I can’t see big advantages to virtual festivals, other than the fact that one can be at two or more festivals at the same time.

How has the film played in Iceland? Did people react very differently from audiences in other countries?

It is hard to say since I have only seen it in the cinema with Icelanders. It played extremely well in Iceland and received numerous awards in the Nordic countries and Spain. But yes, from the online reactions I’ve seen, it does seem to play much better in certain countries. Perhaps there is a cultural barrier and/or I may have been dead wrong about intonations being omni-universal. Who knows, but now I’m just looking forward to my next project.

Halldórsson answers were sent by email.

Final Oscar voting end on April 20. The winners will be announced at the ceremony on April 25.