Erick Oh On ‘Opera’ (Oscar Shorts Interview Series)

Every day this week, we are focusing on one of the five nominees in the Animated Shorts category at the Oscars. Our guest today is Erick Oh, director of Opera.

It’s been said that those who forget history are doomed to repeat it, so it’s a good thing that the work of animator and director Erick Oh is so determined to remember.

A Korean animator and filmmaker based in California, Oh has worked as an animator at Pixar (Inside Out, Finding Dory) and a writer and director at Tonko House (Pig: The Dam Keeper Poems), while also directing his own projects. His independent shorts are focused on a kind of reciprocity, constantly changing structures that appear to be a part of a larger loop, the minuscule and often whimsical characters paradoxically representative of huge swathes of human history.

Opera is Oh’s latest anthropological project, a quirky and existential animated take on Renaissance mural paintings that similarly distills grand concepts into one spectacular tableau: a view of a giant pyramid, filled with a hierarchical society. It appears as a living organism, mechanical in how its inhabitants go through repetitive rhythms, but apparently alive in its constant motion and perhaps even through its self-destruction.

The film slowly cycles through day and night as it invites examination of each section and the individual characters’ activities, all intrinsically linked in fascinating and thought-provoking cause and effect. On the back of its Oscar nomination, we called Oh to discuss Opera, cycles of history, and the ups and downs of making an independent film.

Cartoon Brew: I was immediately struck by the resemblance of the film to Botticelli’s Divine Comedy illustrations. Why this particular art style?

Erick Oh: Opera definitely started from the subject matter. I wanted to showcase a reflection of human society and history — I immediately thought about what would be the best way to convey our life, and realized that maybe following the conventional, linear narrative structure may not be the best way.

Conventional film language has the beginning and the end, a climax. History doesn’t work that way. Our life is one continuous rhythm, so that’s why I came up with this structure of the cycle, so we can watch this numerous times and embrace everything happening.

So once the loop was sorted, I wanted to have the stories happening all at once. Like how in certain sections of the world, there’s a war going on, and on the other side of the globe, there’ll be a happy festival.

That made me think of the mural fresco paintings you just touched upon, Renaissance mural paintings like Bosch or Michelangelo. There are people, sometimes hundreds of people interacting with one another, so many vignettes and stories in every little corner, you know. So I thought that I’d love to make a contemporary version of a mural painting.

I understand that Opera was conceptualized as an installation piece: something constantly moving by way of a looping day and night cycle. What led you to construct the project this way?

Actually I was thinking of two different versions from the get-go: something we can enjoy as an installation piece and also in the theater. Though of course, none of us expected the pandemic. One takes full advantage of the cinematic experience, with the darkness, surrounding audio, and the big screen. Then the other one — that doesn’t have any camera movement — you just walk in, you see this huge pyramid structure. And then it’s really up to you to walk around and get closer and see the ending and the beginnings of each section all blended together. So just one looping cycle, two different ways.

It’s a fascinating visualization of what the everyday means to different people. When you were imagining what the pyramid looked like, did you start with the top or the bottom?

The triangle or pyramid shape was there from the very early stages. I realized that the pyramid is really the iconic shape that could basically capture how our civilization is structured, what our society is built upon. So from there, I’m going to start telling story within this triangle. Then I thought, as you said, “Where should I begin?!”

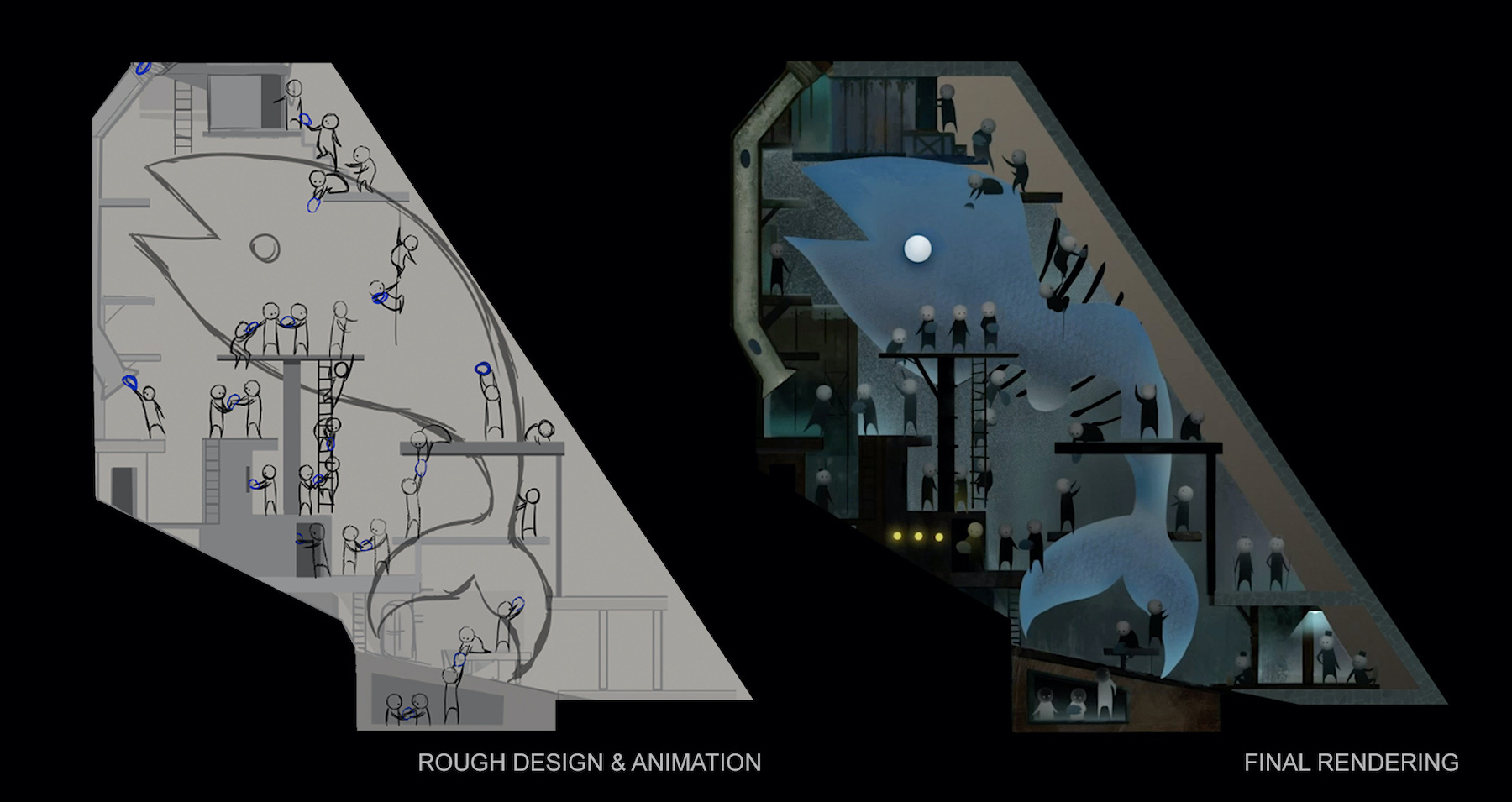

I thought about all these small sections and segments, like these small moments in our lives, and I started laying it all down. It almost felt like doing puzzles: “This piece goes over here. And this line of action, the consequences could influence this area. Oh, that doesn’t work — let’s try it over here.” I’d flip things left and right, upside down [laughs]. It took me about four or five months to really complete this blueprint of the pyramid.

It’s very intricate, how all of the different pieces interact and how their stories unfold. Did you work with a script at all?

I had the broad strokes of the storyline and the structure in the written format, but then immediately, I moved on to drawing because it’s such a visual piece, it doesn’t have any dialogue. So it’s really the explanation of what’s happening in this moment in this area, what happens at night, and all that.

How long did you end up working on it overall?

It took us about four years to fully complete the piece. It was a long marathon, since production started in 2017. But one of the main reasons why it took that long was because it wasn’t our main job. I had a day job. All my artists, crew and team members, were actually also doing it in their spare time.

So there was a number of months where I wasn’t able to even touch any of Opera because I was so busy working on other projects. If Opera had been the only piece I was working on, I think it could have been done within a year for sure, since I had a team of about 34 artists.

Speaking of the team: I wanted to ask about your collaboration with sound designer Andrew Vernon and how you created audio that actually feels universal.

Audio is a big piece of this — well, the title is already Opera. With the sound effects and sound design, we wanted to create an experience that if we just look at it, you don’t even know where to look at first, right? It’s hundreds of people interacting, so the sound is designed to be chaotic at first glance.

But if you decide to focus on one certain thing, there’s then a corresponding sound. For example, there’s the guillotine and prisoners about to get their heads chopped off, and it makes this [mimics guillotine noise] sound. But at the same time, we didn’t want any of them to actually stand out, so everything’s at the same level. And then there’s music to tie it together. Through that there’s still a bit of narrative, a climax and a resolution.

One of your previous shorts, How to Eat Your Apple, had a looping and changing structure as well. What draws you towards these environments?

Well, first of all, glad that you touched upon How to Eat Your Apple. Looking back, I think it could almost be where the idea for Opera originated, like a smaller baby version of it. I think both really carry a very similar approach, a similar process.

Going back to your question, I think it simply comes from looking at the world and cycles of life and knowing you can’t control it. It constantly evolves and changes and transforms, and comes back to where it used to be. That cycle, that link, is something I always want to convey. So not just How to Eat Your Apple but even my other, more linear stories. You know, they also give you the hint that this is going to start all over again.

So do you see animation as a way to sort of emphasize life’s repetitions?

I think so.

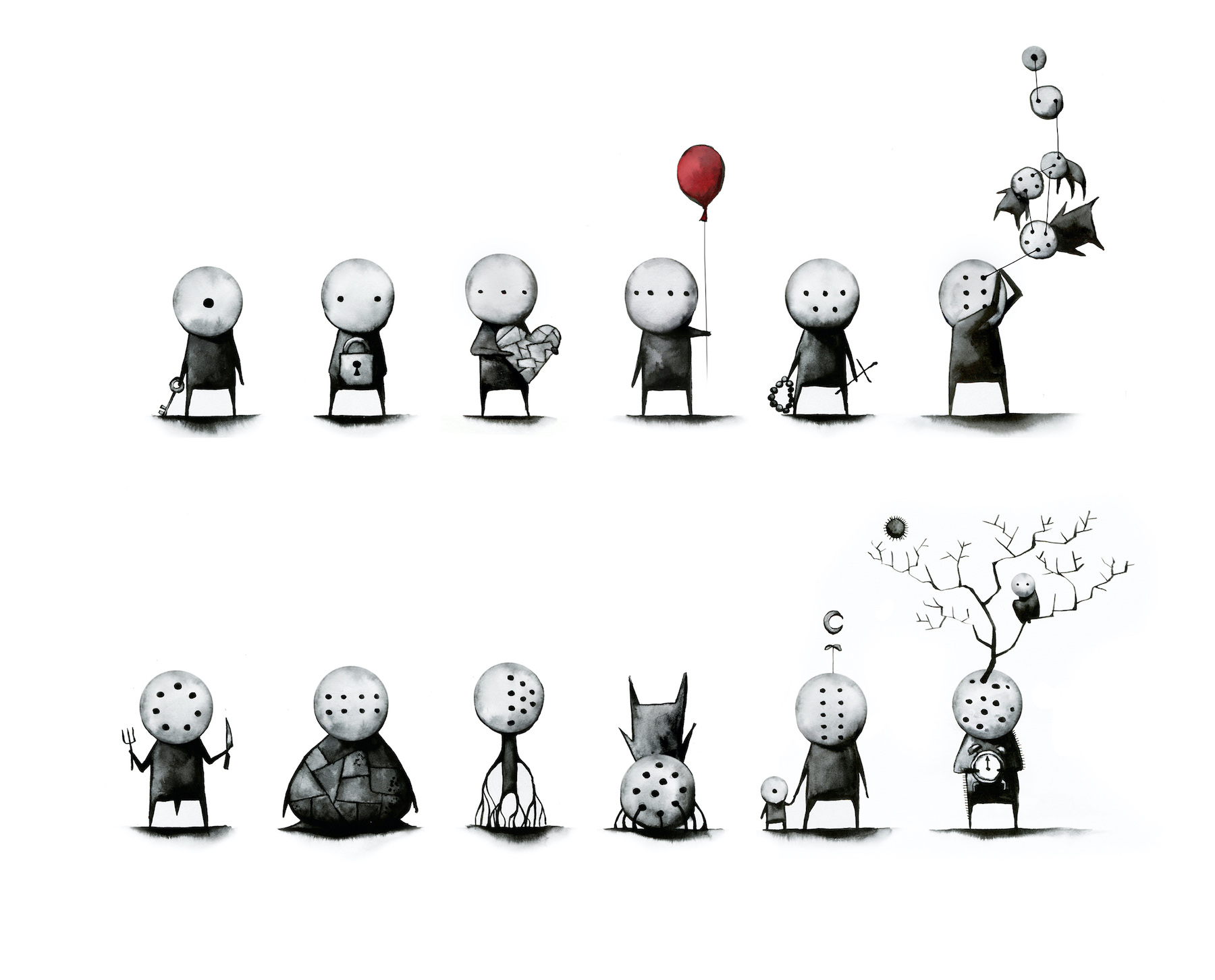

I was very interested by the simplicity of the character designs in both.

Yeah. It’s super generic on purpose: I didn’t want any one character to carry all the emotion of the piece. I wanted to almost see these “Earthlings,” this crowd of people from afar. So that’s why I went with this super straightforward black-and-white color scheme, and I didn’t even bother giving them ears or noses. I think that minimalism provides more room for more diverse interpretations.

Were there any sorts of audiovisual installation projects that you were looking at when you were thinking about what Opera might look like?

I can’t think of specific artists’ names, but I was definitely inspired by some projection-mapping works. Have you heard of this artists’ group named Teamlab? They are Japanese artists specialized in that type of art — they use projection mapping to make these immersive spaces where you’re surrounded by moving visuals. I was inspired by that too.

You spoke about starting Opera in between your other work. How did you go about funding this project?

It’s the big question for artists who love to make this type of film. I think for Opera, seeing the light of day was a miracle. Half or even two thirds of the production was done without any budget, believe it or not. So it was really a voluntary collaboration, you know, with my colleagues and fellow artists and their love and passion.

So of course, I had two options. One: you shop this around to different people, try to get funding. I already knew that I didn’t have time to pitch this and run around to meet these people, so I thought I’d take the other option: I’ll just start doing it on my own. Maybe I can ask my buddy sitting right next to me.

I got to work with a lot of Pixar artists who are basically my best friends, and it was very different from what we do in our day-to-day work. And with time the piece got slowly actualized. And I was able to take this to some investors and get some small funding for post-production and distribution and everything.

Sounds like it was cathartic in two ways: you get to visualize how you see the world, and simply get to work on something different to the norm with your co-workers.

Oh, totally. For example, Andrew Vernon, the sound designer. I’ve been working with him for almost ten years now. We’ve been best friends; he worked on How to Eat Your Apple, and that came out around 2012 or something. He’s been always my go-to sound designer and he’s always like, “Hey, Erick, you always do crazy stuff, you ever have anything on your mind, let me know.” So yeah, I really, really appreciate all the support and love from my friends in the industry.

What was the most pronounced difference between working on this and your time at Pixar as an animator?

You know, it’s the same and very different. I guess the same in terms of, you are still the one telling the story, you still believe in what you’re working on. When I was working on Pixar projects, I really believed in those projects — they’re trying to give the audience something very meaningful. So that ultimate goal is the same, but of course, the approach is all different.

When it comes to Pixar, we are talking about 500 people for four years, all working on the same project with a huge, huge budget. And as an animator, you usually are the one acting out the character, you are the one producing the motion and movement in this character that’s going to be shown on the screen. It’s like you’re one actor in this big Hollywood movie, versus being the director of this indie film. That’s, of course, a huge risk and it’s not easy, but it’s rewarding, because everything, all the small and big decision making, it’s all coming from you.

Were there any other challenges that came with working independently?

Well, every single step was the challenge [laughs]. It was mostly practical things. But you know, other than time, I got to say that the biggest risk to this project is that it didn’t really have a deadline. Honestly, some filmmakers say that meeting the deadline was the really challenging part. And really, that line is, “I wish I had a few more days.”

Not having that, you think, “Okay, no one’s losing any money, no one’s going to be, you know, mad.” That’s kind of a big risk. I could be like, one day, “Hey, I don’t want to make this,” and that’s the death of the project. Not having a producer has been the most challenging part because I had to be constantly self-motivated, constantly ask myself and motivate the artists.

Of course, looking for talent was hard too, because even though I did get the funding for distribution at the end, it’s practically a personal favor.

Oh’s answers were edited for clarity and brevity.

Final Oscar voting takes place on April 15–20. The winners will be announced at the ceremony on April 25.