Adrien Mérigeau on ‘Genius Loci’ (Oscar Shorts Interview Series)

Welcome to our series of interviews with the directors of this year’s Oscar-nominated animated shorts. Every day this week, we’ll be speaking with one of the five nominees in the category. First up is Adrien Mérigeau, director of Genius Loci.

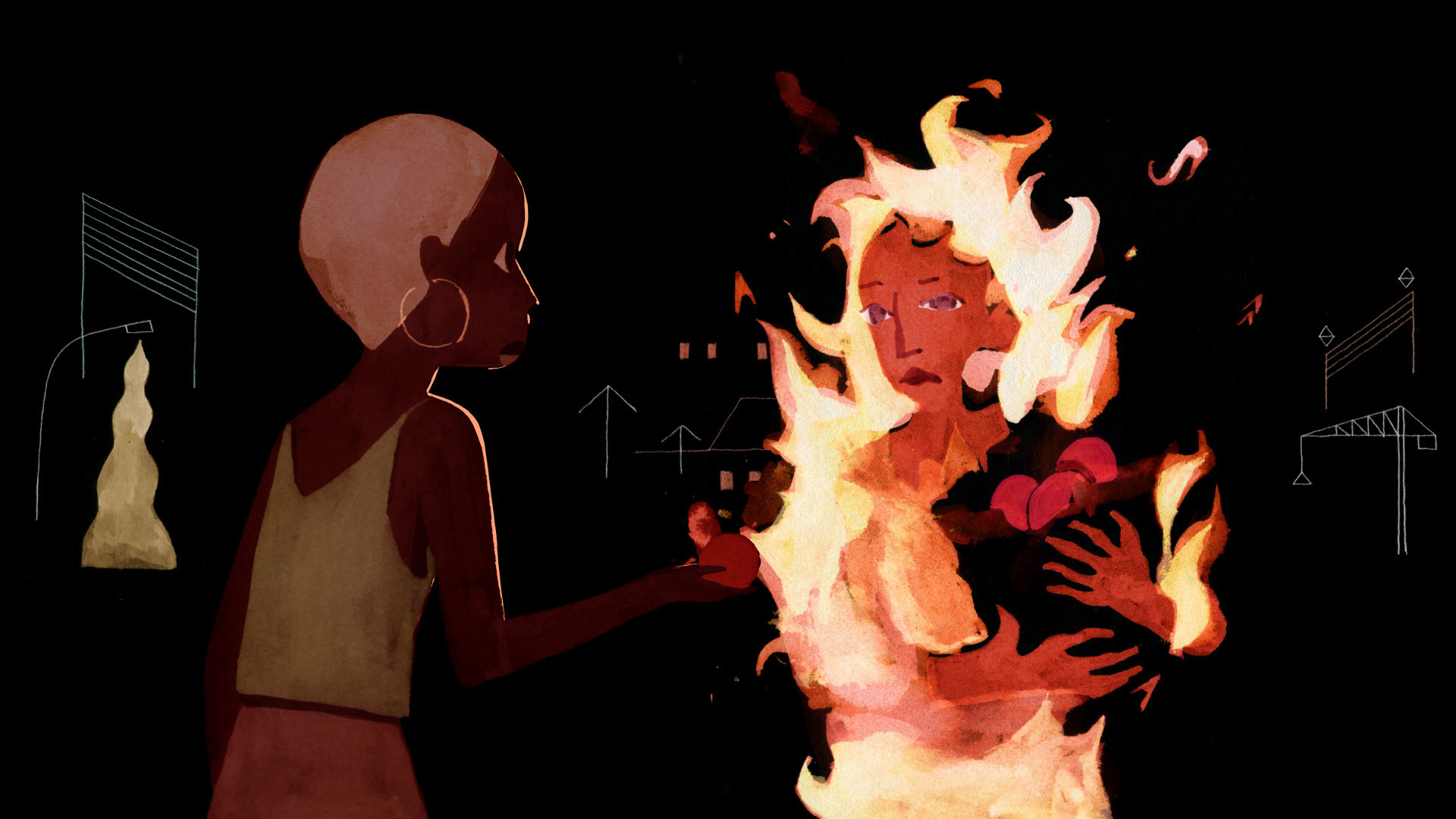

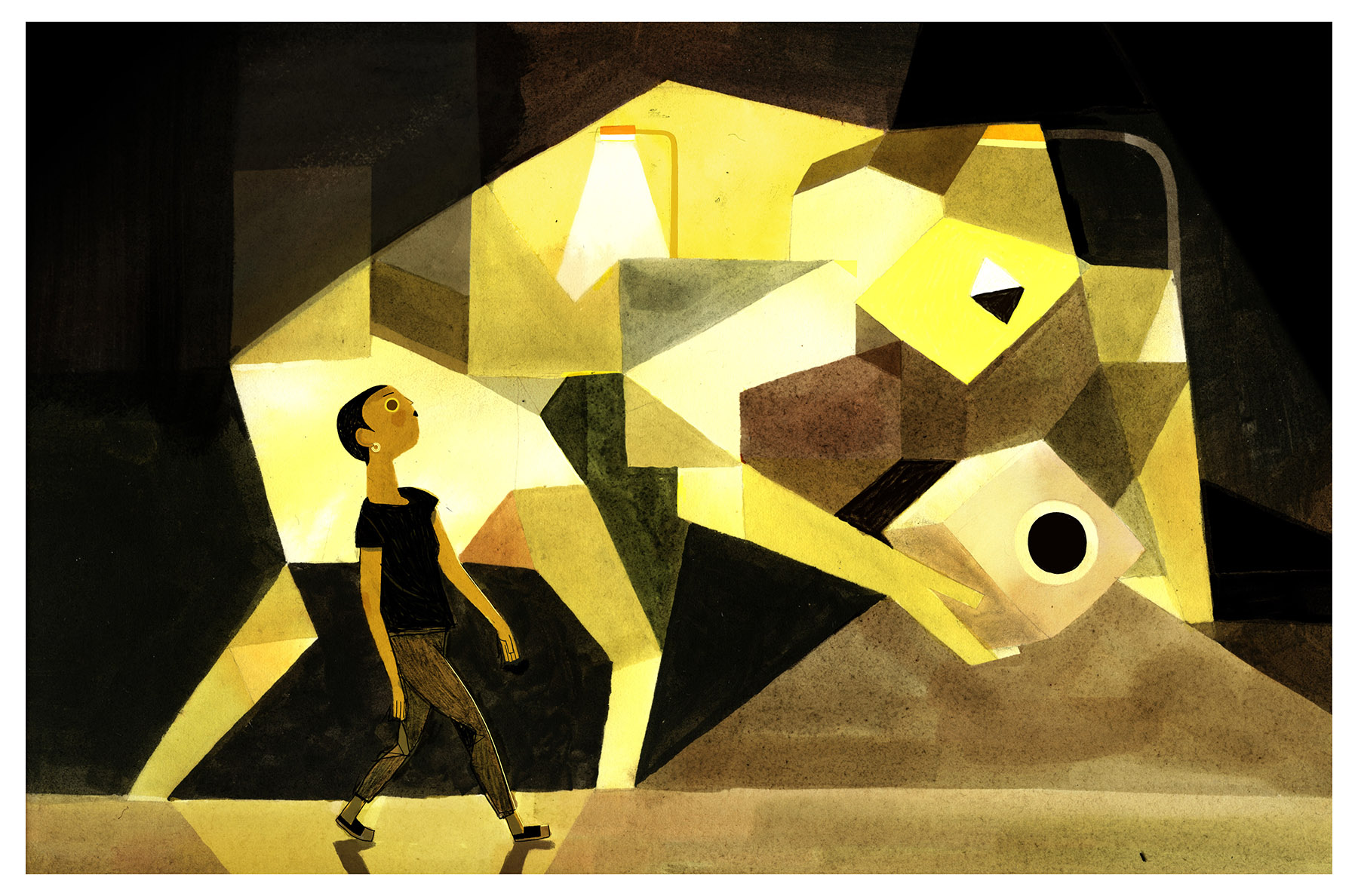

For me, the inclusion of Mérigeau’s film among the nominees was both a joy and a surprise. A portrait of a young Black woman’s stroll through a night-time cityscape — or rather, of her psychological journey as she walks — Genius Loci is experimental, impressionistic, more interested in the subtleties and vagaries of mood than in the clarity of plot. It is startlingly beautiful, but not your typical Oscar contender.

This is the first short film Mérigeau has directed in over a decade (outside commissioned work). His last short was 2009’s Old Fangs, a similarly enigmatic night-set tale made at Cartoon Saloon. Mérigeau spent many years at the Irish studio, working as a background artist on The Secret of Kells (2009) and the production designer on Song of the Sea (2014). Those features share with Genius Loci a highly stylized art direction, with non-linear perspective and arresting expressionistic flourishes.

By the time he started work on Genius Loci, Mérigeau was back in his native France, set up in a studio in the Parisian suburbs. Overcoming his inner “control freak,” the director embraced a collaborative approach to production. He developed the film’s visual style with Belgian artist Brecht Evens (who was also closely involved with the recent animated feature Marona’s Fantastic Tale), called on his family to create the striking soundtrack, and gave his fellow artists on the team a lot of creative freedom.

Below, Mérigeau tells us why the film was so hard to write, how he settled on a Black woman as his protagonist, and what he learned in his time at Cartoon Saloon …

Cartoon Brew: The film’s structure is quite freeform — you have said it was inspired by the intuitive flow of sketchbooks. How did you develop the narrative? Did you have a script?

Adrien Mérigeau: I did have a script that was written about 20 times over two years in order to look for public funds, which are the main support we have to make short films in France. The script and concept art go through reading committees which award projects with funding, or at least precious feedback.

I had a hard time writing the script, as I wanted the film to drift into a contemplative state where the story loses its meaning, and it felt awkward to try and put into words the abstract movement that overtakes the film and the attention of Reine, the main character.

Ultimately I was really happy that, over time, the team and I were able to find a solid narrative base that could accommodate the experimental part of the film. We were always stripping the narration down to what was essential and necessary, and over two years some superfluous ideas just naturally faded and became obsolete. I don’t regret starting with a tedious scriptwriting process: it was long but helped strengthen the film.

You collaborated with Brecht Evens on the backgrounds and mise en scène. How did you come to work with him and what were his contributions, exactly?

Brecht Evens is a magical comic-book artist and overall wonderful person. I discovered his work through Amaury Ovise, my producer, at the start of the writing of my film. Brecht’s work was perfectly suited for Genius Loci: the way he represents the chaos of the city at night, and deforms the perspective of buildings to make the city look like it is alive, is essentially what my film was about.

We reached out to him, but I never thought he had any time or interest in working on a little short film project by some random French animator. We had an amazing meeting where Brecht had already printed the script and written down many notes and sketches that later made their way into the film.

My idea was to collaborate with a few artists with a strong style and offer them a specific part of the film for them to make their own. I really love this collaborative way of working: the style of the film can change all the way through and still feel coherent because we are all friends and I think it shows, the way all the parts click into each other. Other main artists who worked on Genius Loci were Céline Devaux, Alan Holly, Vaiana Gauthier, and Chenghua Yang.

But with Brecht Evens, he did a lot of storyboarding and general story ideas, dialogue ideas, color ideas, and he kind of wrote the film with me, in addition to his key backgrounds that are easily identifiable in the film.

How specific were the directions you gave Evens and your animators? How easy was it to capture that sense of intuitiveness, of spontaneity, while working with a team?

I feel like there were two types of collaborative effort in Genius Loci. Some artists later in production were more technical, in that I already had specific layout poses for the animation and printed-out animation for coloring.

Earlier in the production, there were the artists I mentioned above who took a part of the film and explored the theme and essence of that part with their own approach and style. It was a bit like doing a big puzzle. Some areas of the film were more defined, some not, some completely blank, which was the case for Céline’s black-and-white sequence.

It was really wonderful and easy to work like that, because I am a very anxious and control-freaky person for my own work, and it was great working with artists who were much more spontaneous and intuitive and free. In the end I gave very little feedback — the idea was more about letting the film grow into itself after the team was chosen.

The sound design is beautifully subtle. I believe it was created by your parents and brother. What directions did you give them?

I agree! The sound design and music were both written as one by my parents Lê Quan Ninh and Martine Altenburger, and my brother Théo Mérigeau for the organ part in the church. I gave them no direction at all — only a line-animated version of the film — and they built everything from scratch.

They practice free improvising, and the way I wrote my film was heavily influenced by my parents’ work: how they consider sounds as music, their meditative approach to playing and listening to music, is very akin to my character’s observation and spiritual-like flow state in my film. I really created the film with their music in mind, so the match was evident and I didn’t need to guide them at all — quite the contrary! In any case, they are my parents and you can’t tell your parents what to do. At the end of the day, you are still a kid to them!

Was the character of Reine a Black woman from the start? Women’s experiences of walking through cities at night are quite different from men’s…

That’s an excellent observation. You are right, the character started out as a young Arab demiboy, when my story was based on a friend of mine in Ireland. Later on, the film took its own path, becoming a study of Reine as a Black woman in Paris’s suburban streets.

This transition was natural and made sense to me for many reasons. First as a representation issue: it felt weird that it was so rare to see Black characters in animation in France. Secondly, the meeting with the organ player Rosie later in the film had too much of a heteronormative vibe.

But most importantly, it made sense for Reine to be a dark-skinned Black woman because the world outside needed to be quite hostile to her, in order to show that her relationship with her spirit serves as a defence mechanism against her daily oppressions, and to showcase her strength and the fact that she’s distant and not fazed by anything.

Was Genius Loci inspired by a specific part of Paris (or any other city)?

It is inspired by the place where my studio space was in 2017, the suburb of Paris called Aubervilliers. I was working in a squatted building there and doing exhibitions, community work like dinners and events. I love this place, it’s really chaotic, the streets are full of great people and life, and it isn’t gentrified. The energy in the street can be a bit intimidating but also very joyful, and it feels real. I really love this place.

How did you choose the title?

I stole it from my parents. They had an ensemble temporarily called Genius Loci in 2005. They asked me to design the logo at the time, and I drew a small, yellow protective spirit on a black background. It was probably the first image that was ever in my head about this film. The name is Latin and means “the spirit of a place,” and it has stuck with me ever since.

The film is interested in how we engage with our environments — how, in a sense, places create a kind of rhythm out of the things moving within them, and how we respond to that. So is your previous short film, Old Fangs — except there, it’s a forest. Do you experience cities and nature in essentially different ways?

Yes exactly! Especially in my experiences with occupying empty buildings, a.k.a squatting, the relationship we have with things that are abandoned or broken is similar to how we experience nature. In France, when we start occupying an old empty building, we have to camp in it — with tents, candles, small cookers, the same way we’d do in nature. In between slabs of concrete, useless machinery, and debris, it feels like we’re in a forest.

In front of abandoned things, we look at their shape, their movement, their sounds, instead of what their use is. This state of observation can be meditative and spiritual, and our experience of chaos is the epitome of that, because you never know what’s going to happen next. You can observe the phenomenon, like water spilling from a knocked-over glass, and feel connected to it in some way.

These reflections were what fascinated me most about writing Genius Loci, but also the reason why it was such a challenge to write it. I’m so happy you picked up on it!

Old Fangs was produced at Cartoon Saloon. What was the most important thing you learned while working at the studio?

Cartoon Saloon was my home for ten years and so much of the essence of my work is from there. I learned storytelling, composition, the passion of 2d animation, and kindness from Tomm Moore, and watercolors and lighting from Ross Stewart, most importantly.

I gained a lot of confidence thanks to their family-like support, and I had the opportunity to learn and grow as I worked on The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea, which led me to the opportunities I got to make my short films. These days I am influenced by contemporary art, graphic design, and tattoo design, mostly. But the core and structure of what I do, I learned it at Cartoon Saloon.

Genius Loci spent much of its festival run playing in virtual festivals. Do you regret this? Did it bring any advantages?

Yes, it was really sad to see that Genius Loci’s festival run was mostly online, especially when it was selected in festivals that are very meaningful in a filmmaker’s life, such as Annecy, GLAS, New Chitose Airport, Go Short, and more. When we do short films, the festival experience is the only time we can meet our audiences, show our films, and get the feeling that we are sharing our long and trudging work, because we don’t have global releases like full feature films do.

Thankfully I was able to go to three different festivals, including the Berlinale, right before the pandemic started, but I have friends who are releasing their films now and are unlikely to have a screening with an audience for a while yet, and it is very difficult for them mentally. I can’t think of any positive sides to the virtual festival experience.

At the moment we are still hopeful that we’ll be able to go to the Oscar ceremony at the end of April. If we can’t, for sanitary reasons, I’ll be really bummed.

Mérigeau’s answers were sent by email and edited for clarity.

Final Oscar voting takes place on April 15–20. The winners will be announced at the ceremony on April 25.