Series Craft: How A Thriving Ecosystem Was Built Mostly From Paper For ‘Hello World!’

Welcome to Series Craft, a new site feature in which we explore a particular creative facet of animation production in depth and discuss the choices that lead to the finished result. In this installment, we explore the puppet making on the French film/series Hello World! (Bonjour le monde !) with co-directors Anne-Lise Koehler and Éric Serre.

Shortly before the pandemic, while attending an animation festival in the Parisian suburbs, I was invited to a local artist’s studio. Stepping inside, I was greeted by a menagerie: owls and bitterns eyed me from shelves, beavers and salamanders peeked out from within plastic containers, and a pond skater or two stood frozen by my feet.

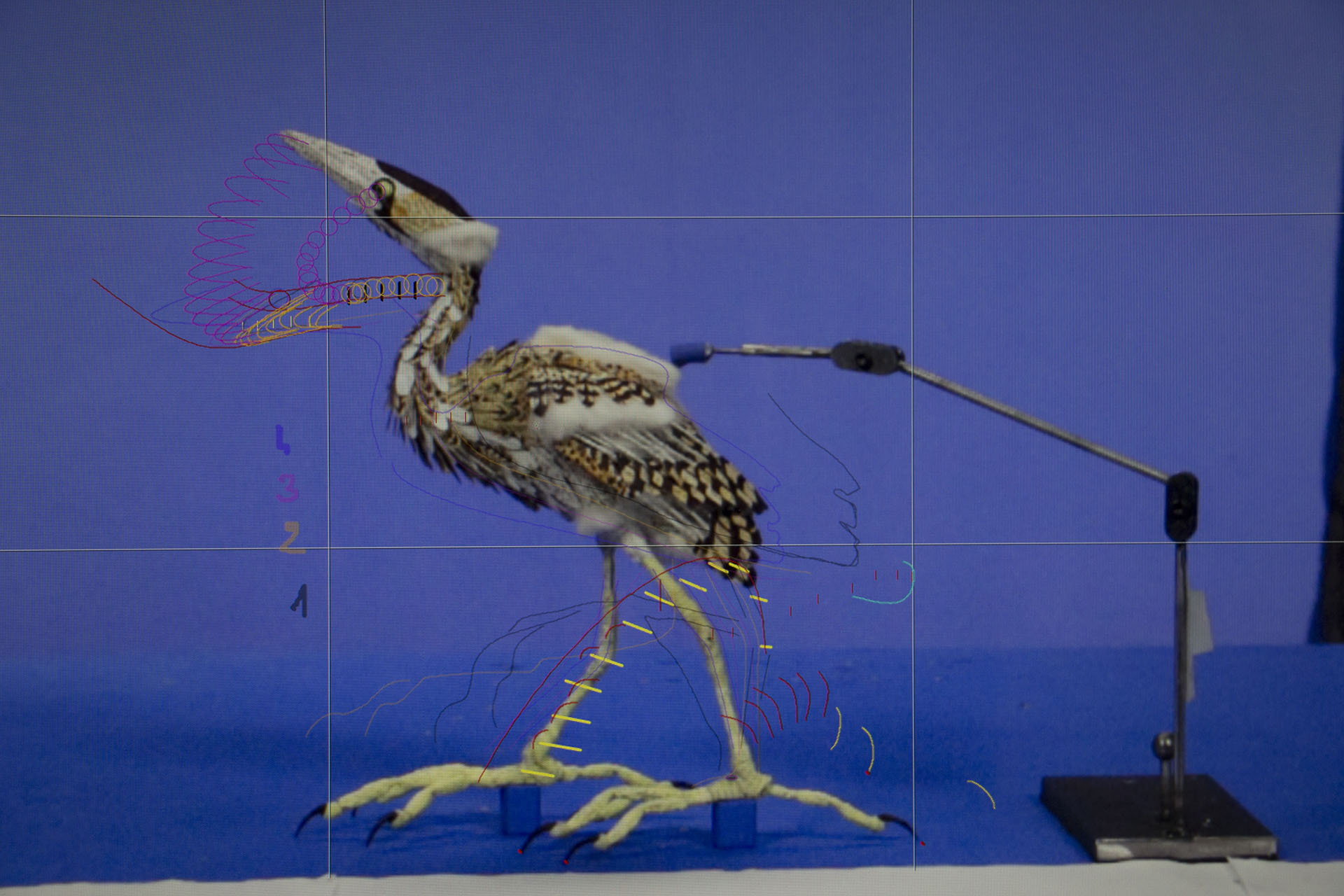

That the animals were all crafted from papier mâché made the scene, if anything, more striking: this was a private zoo like no other. Each creature was a puppet, carefully hand-crafted for use in the stop-motion show Hello World!. The artist whose studio we were in was Anne-Lise Koehler, its writer and co-director, and the mastermind of its arresting design.

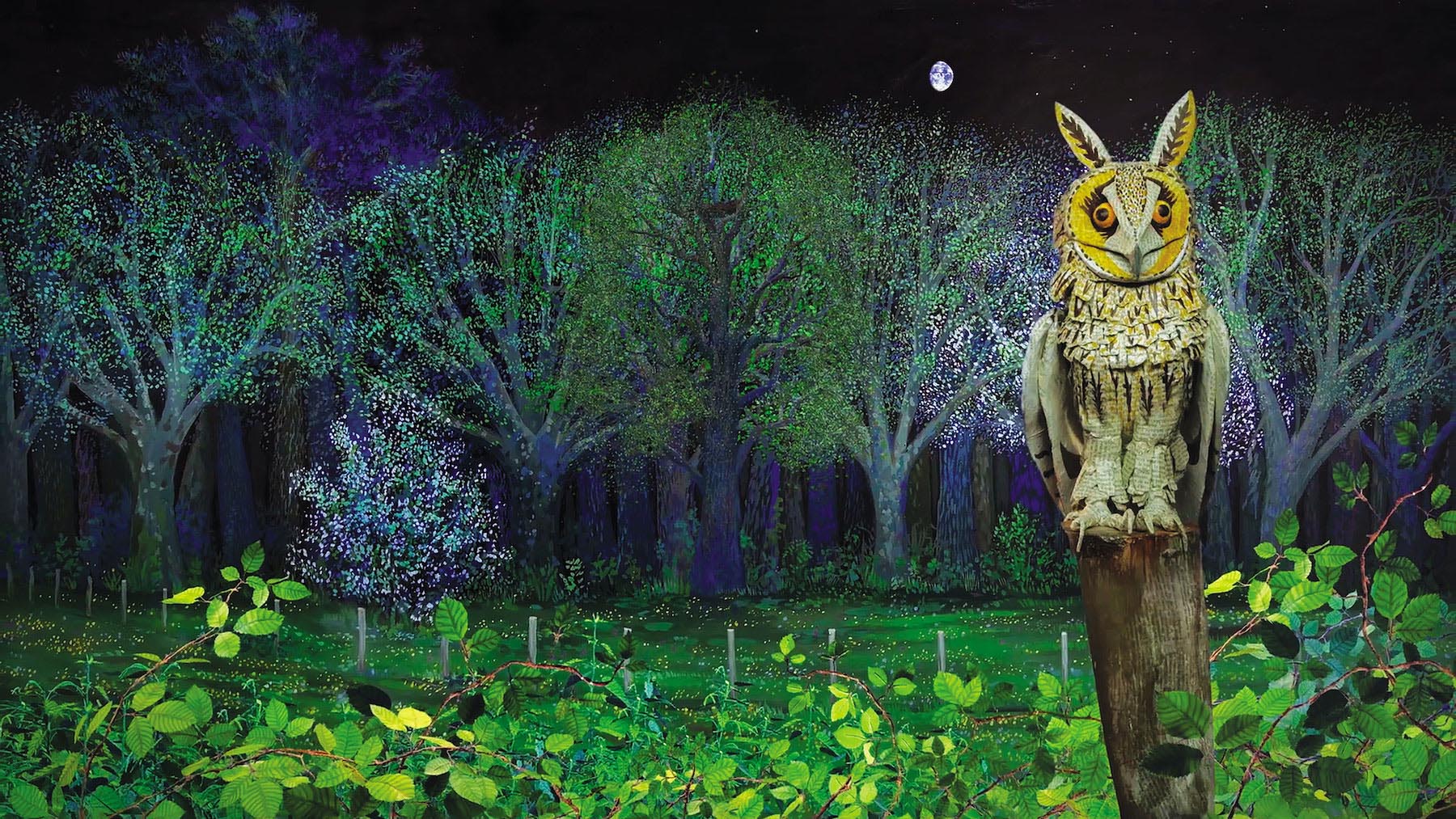

Hello World! was first released as a series, winning Annecy’s prize for best tv production in 2015; it was later reworked into a feature, which included more than a hundred new shots. These episodic origins come through in the film, a gentle, meandering tale of ten species who inhabit a vibrant ecosystem. Insects, mammals, amphibians, and birds are born and grow up, expressing wonderment at their environment (we hear them speak in voiceover), but also falling prey to its dangers.

Papier mâché is an unusual material in stop-motion animation, but it works here: the characters move with great personality and delicacy. Remarkably, neither Koehler nor her co-director Éric Serre had a track record in the medium. Koehler production-designed Michel Ocelot’s films Kirikou and the Sorceress and Azur & Asmar: The Princes’ Quest; Serre did layouts on both, also serving as assistant director on the latter. The pair then co-directed the special effects in the live-action nature documentary Once Upon a Forest.

Hello World! was produced at Normaal Animation in Paris and Angoulême, France. In all, the small team created more than 110 puppets representing 76 animal species, as well as hundreds of sculptures of plants. Koehler and Serre were both closely involved across the production, Koehler serving as art director and painting the backgrounds, Serre working across storyboards, animatics, layouts, animation supervision, and more.

The pair are now continuing their collaboration with Immersion, Augmented Nature, an upcoming ar project that returns to the habitat of Hello World!, but is animated in Blender; the project was presented as a work in progress at Annecy last month.

Below, Koehler and Serre reflect on the creation of their remarkable fauna in Hello World! …

Choosing the medium

Koehler has been enthralled by nature for as long as she can remember. “Contemplation of nature is a lesson in humility, love of difference, and diversity,” she says. The birth and infancy of animals seemed to her a good subject, “because all living beings, including us, are going through this extraordinary and memorable experience, although there are so many ways to experience it.”

Stop motion with paper puppets struck Koehler as the appropriate medium: “The animation of this inert matter which comes to life has a moving and wonderful power. It brings us back to the mystery of our own existence.” Yet this choice posed a challenge. Most stop-motion animation features anthropomorphic puppets, and papier mâché is a relatively rare material. As such, the team didn’t have many reference points for their work.

Koehler had in fact previously made paper sculptures of animals, so stop-motion puppets were a natural progression. As with the puppets, she would begin each sculpture with a skeleton structure. But the fabrication process diverged after that, as the puppets had to be able to move, of course.

Making the puppets

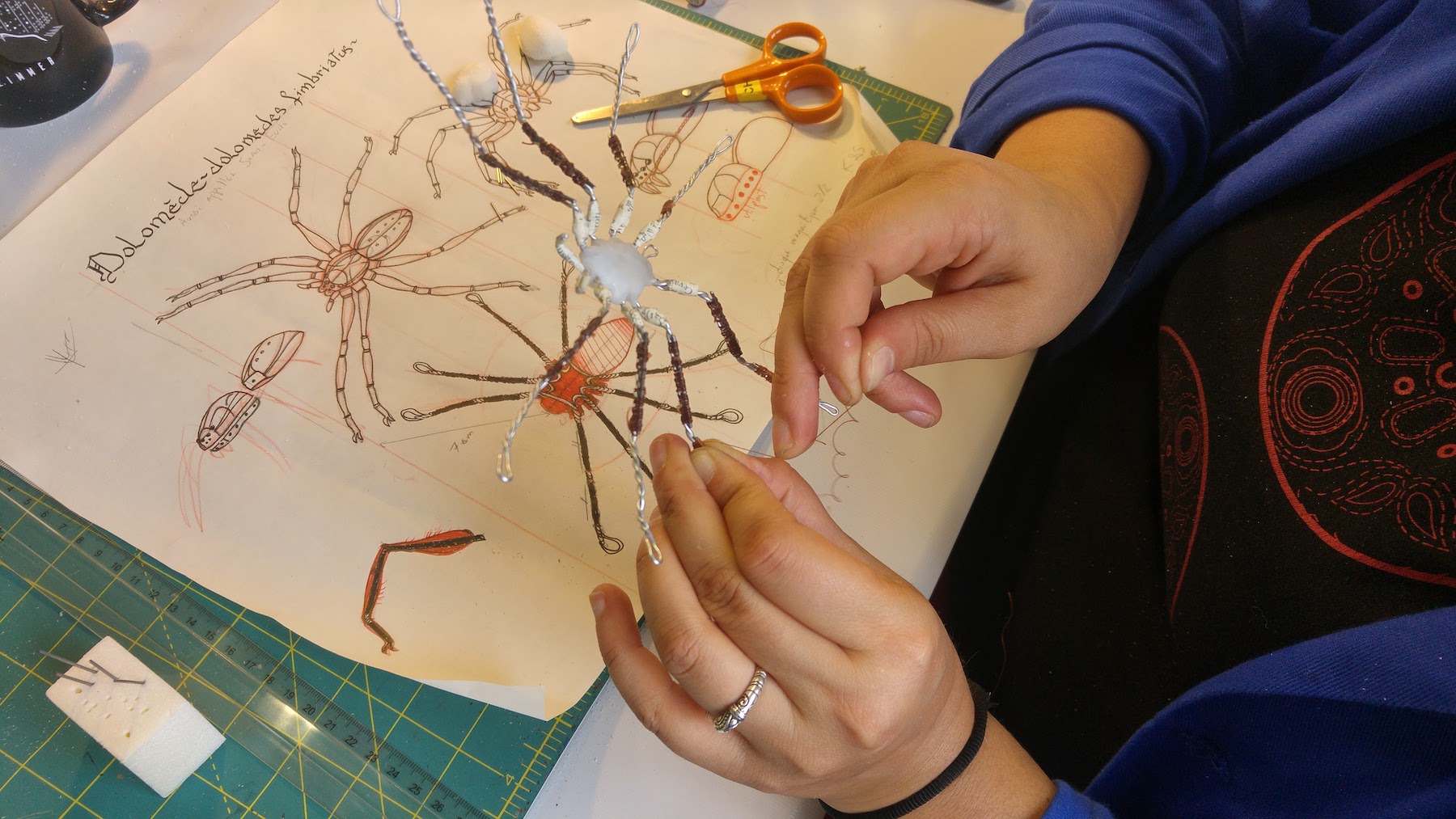

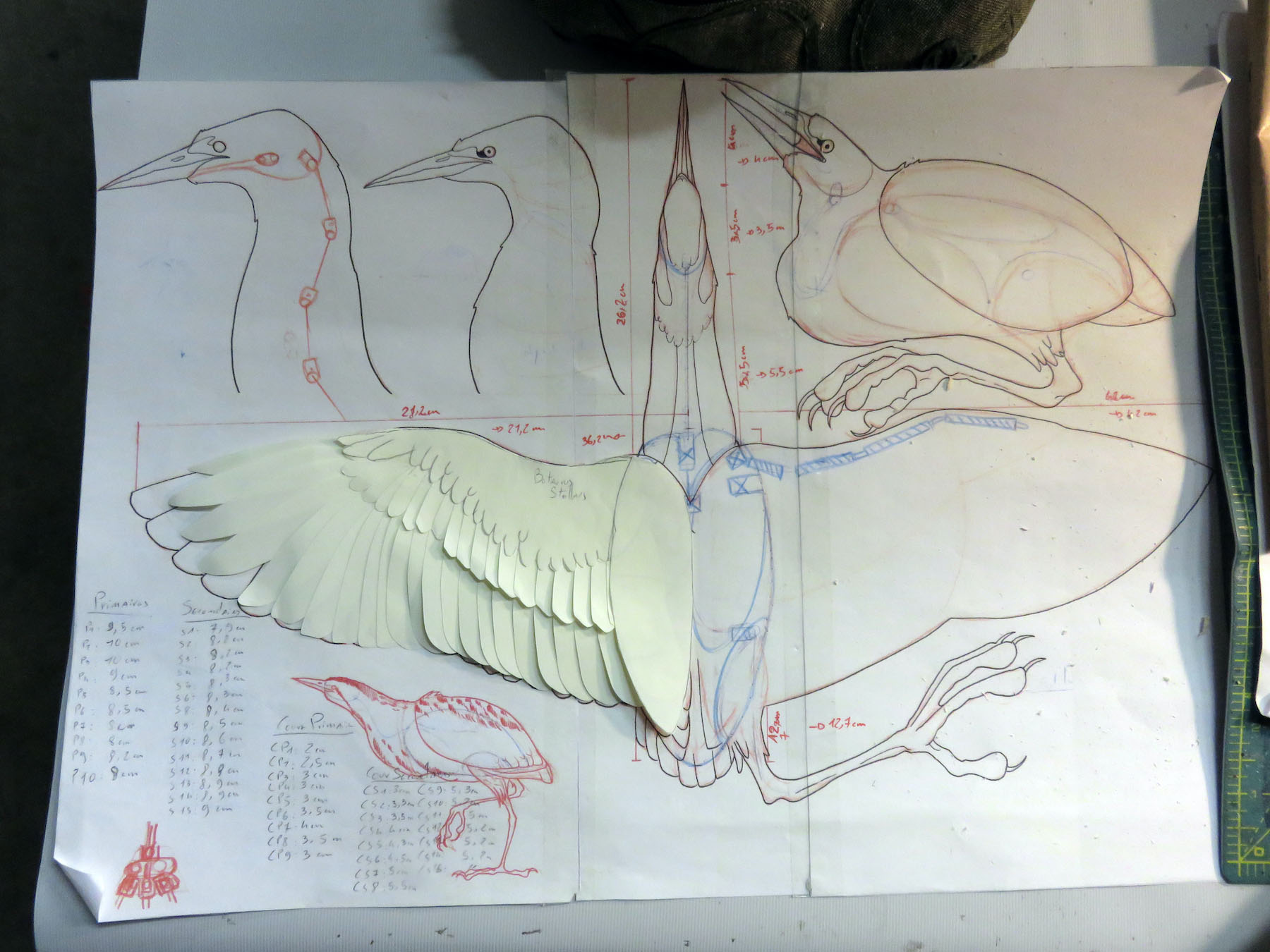

The puppets were made by a team of 15, including Koehler and joints engineer Sam Dhaussy. Each artist started by making a life-size sketch of their puppet, says Koehler. “We didn’t have ‘model sheets’ — each puppet was a special creation adventure.” The artist would then make the animal with wood, paper, fabric, and sometimes polyether foam. “After that, I checked the mobility and painted it to keep the same art direction though the project.”

Paper never posed a problem for the team, according to Koehler: “It is a very strong material, easy to sculpt, light, and resistant to use.” Serre adds, “The material’s rigidity is sometimes restrictive, hindering the articulations.”

The team tore their material out of books in France’s La Pléiade collection of classic literature, which uses suitably thin paper. Koehler chose works by authors she likes. A lawyer friend offered the production his old legal books, which covered matters like divorce and fraud. “Seeing all these bad words written made us sad,” says Koehler. “We decided to cover it all with poetry.”

It initially proved hard to gauge the right size for the puppets. The first one Koehler made “was a life-size long-eared owl puppet. When it opened its wings, it had a wingspan of about a meter [3.3 feet], which raised mechanical problems even with very good ball joints.”

Following advice from Barry Purves, an animator she admires, Koehler aimed to make subsequent puppets 10–30cm (3.9–11.8 inches) long. The longest puppet, the big pike, measured 50cm (in nature, these fish can reach five feet). Others were tiny, such as the fish eaten by the birds, which needed to be proportional to the size of the predators’ beaks.

Animating the animals

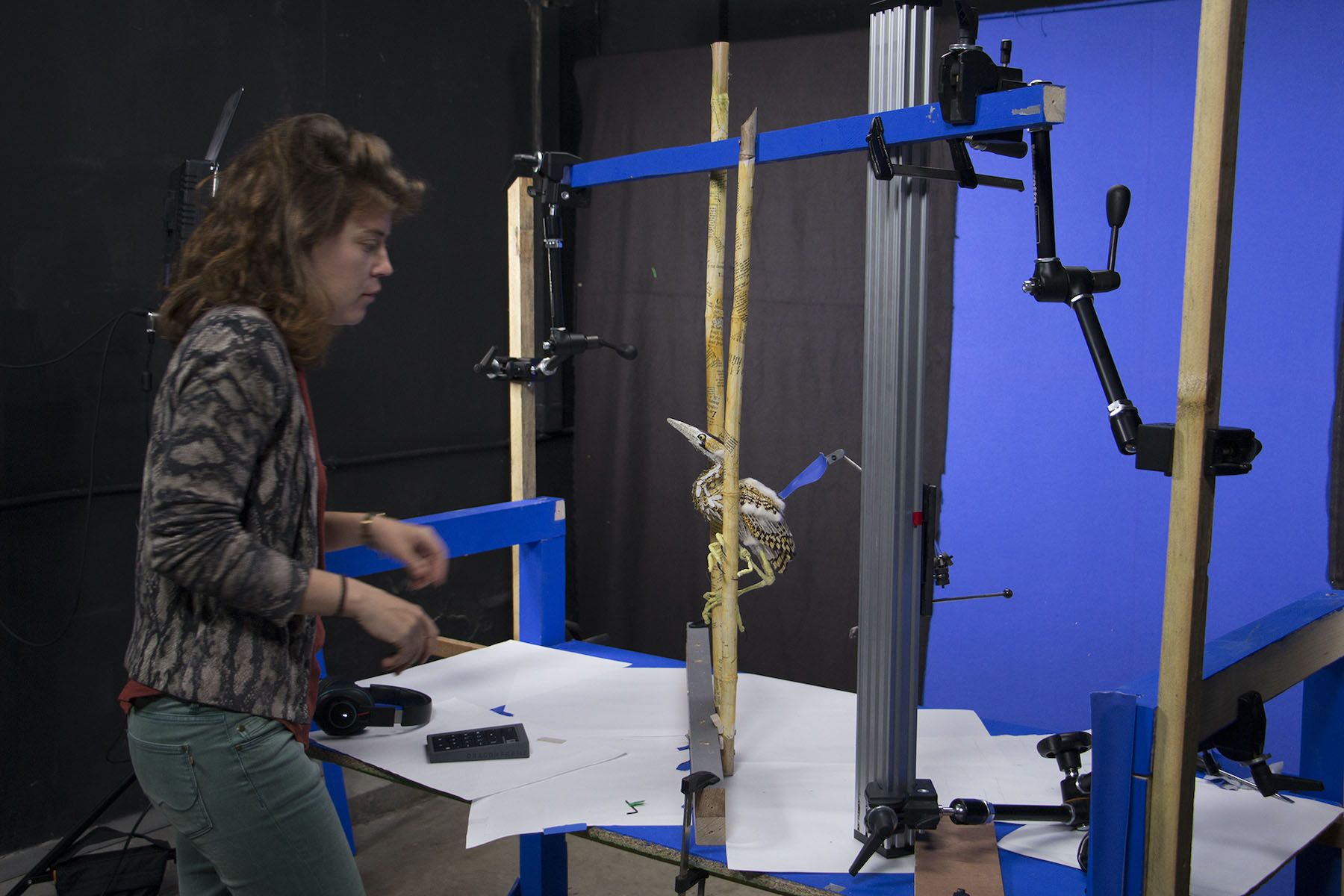

Twelve animators worked to bring these animals to life. Some, like Koehler and Serre, had no experience in stop motion. Serre found this stimulating: “We are here to learn and invent, this is the salt of our job. I also seemed to quickly recognize the strategies of traditional animation: a strict production plan, a camera frame by frame…”

Although the directors saw parallels between animal and human life cycles, they didn’t want the characters to behave like people: the animation had to reflect how animals actually move. “I’d say that the boar, the beaver, and the marten were particularly complex to animate,” recalls Serre. “Supple mammals are difficult to make move.”

But the artists were encouraged to channel their own personalities into their work. “Our animators added their soul to the animals while animating them,” says Koehler. “This project is a team accomplishment.”