Yōji Kuri, Pioneering Japanese Indie Animator, Dies At 96

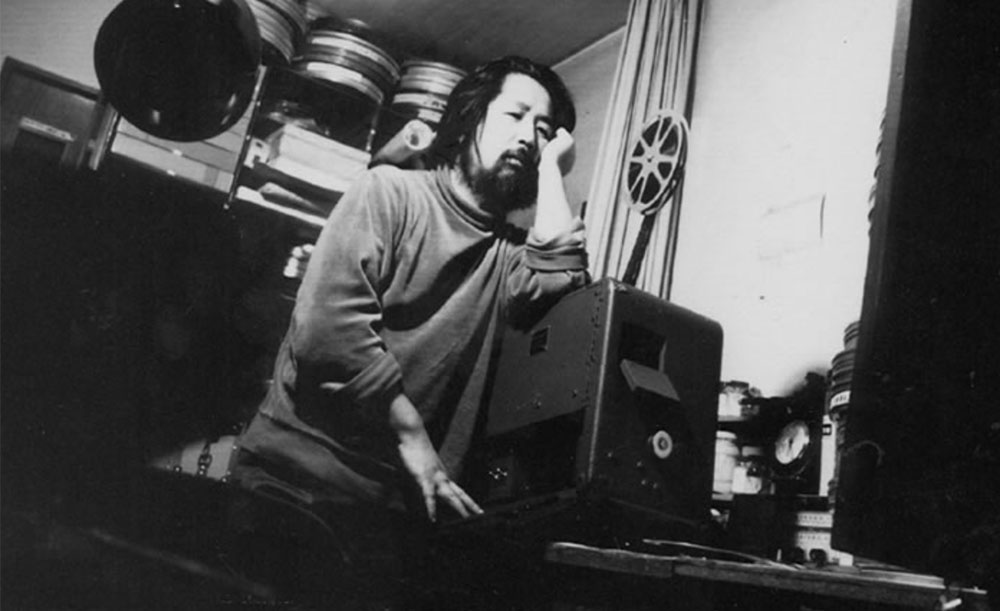

Yōji Kuri, the legendary Japanese animator and filmmaker, passed away from natural causes on November 24, 2024, at the age of 96. His death was announced on December 14 via his social media and official website. A private wake and funeral service are to be held.

Born Hideo Kurihara on April 9, 1928 in Sabae, Fukui Prefecture, Kuri was celebrated for his surreal and biting animated shorts, which challenged conventions in storytelling and societal norms. Inspired by the satirical works of newspaper manga artist Taizō Yokoyama, Kuri defied his family’s disapproval and moved to Tokyo to pursue a creative career. After graduating from the art department of Bunka Gakuen University in 1956, he started as a one-panel satirical manga artist for Kyodo News, earning the prestigious Bungei Shunjū Manga Award in 1958.

In 1960, Kuri partnered with two other illustrators – Hiroshi Manabe and Ryohei Yanagihara – to form the organization Animation Group of Three (Sannin no Kai), which is widely considered to be the beginning of independent animation production in Japan. Kuri became the most prolific of the three and started winning awards at major film and animation festivals around the world, including an award at the Annecy animation festival in 1963, where he became the first Japanese filmmaker to ever be honored by the event.

Kuri’s influence in animation was profound and his films carved a unique path for Japanese animation, moving it away from cozy, narrative-driven works into realms of graphic and conceptual experimentation. His films often mocked modernity and critiqued societal issues like overpopulation, consumerism, and urban alienation. At their heart, they reflected Kuri’s disillusionment with Japan’s rapid post-war transformation and the rise of materialism.

In Two Grilled Fish, an early work, Kuri critiques modernization through the story of a couple who build a peaceful life on a deserted island, only to see it destroyed by industrialization, pollution, and war. Similarly, The Man Next Door portrays a man seeking refuge from noisy neighbors, only to find himself in an even worse environment — an allegory for Tokyo’s overcrowding and urban chaos.

Kuri’s films brim with cynicism. In The Window, he depicts a city apartment as a microcosm of vice and despair, while Au Fou humorously yet darkly addresses violence and Japan’s struggles with suicide. Relationships are also stripped of romantic ideals; in Human Zoo, a man and woman locked in a cage engage in brutal and dehumanizing interactions. Its sequel, Love, pushes the theme further as a woman obsessively chases, devours, and discards a man in a grotesque cycle.

Thematically, he often explored the monotony of modern life, the tension between individuality and conformity, and the violence lurking beneath societal norms. Works like The Chair choreograph everyday human movements into absurd, mechanical displays, questioning the frenzied pace of contemporary existence.

Kuri also delved into stream-of-consciousness and avant-garde animation, often blending surrealism with harsh social commentary. In The Midnight Parasites, he depicts a barren landscape populated by grotesque creatures locked in cycles of predation, embodying his dark view of humanity. His collaboration with Yoko Ono on AOS combined her avant-garde vocalizations with surreal black-and-white visuals of dismembered body parts, emphasizing isolation and disconnection.

Stylistically, Kuri’s minimalist, experimental approach stood in stark contrast to the Disney-inspired traditions of early Japanese animation. Instead, his work drew from Western influences like James Thurber, Saul Steinberg, and the Zagreb School of Animation. His films’ surreal, graphic aesthetic and satirical edge redefined the possibilities of animation in Japan, paving the way for future animators to embrace bold, unconventional storytelling.

Besides his personal shorts, beginning in 1964, Kuri created a weekly animated segment for the Nippon Television Network program 11 PM. The series, titled “Mini Mini Animation,” ran for 18 years.

Director and animator Koji Yamamura reflected on Kuri’s passing, telling Cartoon Brew:

When I heard the news of Yōji Kuri’s passing, I thought that one era of Japanese independent animation had come to an end.

In the 1970s, Kuri, a taciturn artist, appeared every week on late-night tv as ‘Kojimachi no Musina (Badger in Koji-town),’ presenting his freewheeling short animations. Those nonsense animations cracked the ordinary and gave us glimpses of other worlds.

The intensity of Kuri’s animated shorts and his influence through the Animation 3-nin no Kai (Three-Person Animation Club) in the 1960s illuminated a path different from Japan’s industrial animation. Collaborating with leading musicians and graphic designers like Toru Takemitsu, Yoko Ono, Makoto Wada, and Tadanori Yokoo, Kuri’s work inspired countless creators. Unfortunately, such a creative synergy feels hard to replicate today.

Taku Furukawa, an animator and close friend of Kuri’s, also shared his thoughts:

When I was a student, I was deeply moved by Human Zoo. The film changed my life. Since then, Kuri has been my master — not just in animation but in life. People often misinterpret his work as being about the battle between men and women, but it’s much deeper. He says, ‘Look at the human zoo; love humanity.’ Rest in peace, Kuri-san.

Kuri’s legacy is that of a playful provocateur who dared to question, subvert, and redefine the boundaries of animation. His films remain a testament to his unflinching critique of modern society and his visionary contributions to the art form.

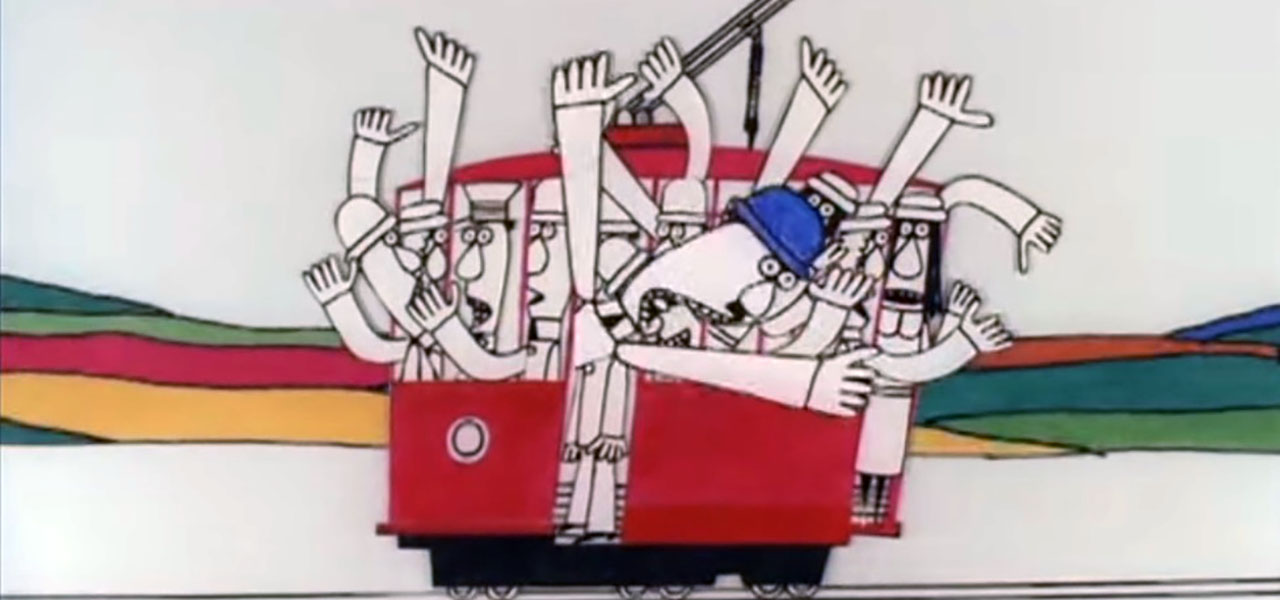

Pictured at top: Yōji Kuri’s 1968 short film Love of Kemeko.