Walt Peregoy, ‘101 Dalmatians’ Color Stylist, RIP

Walt Peregoy, the legendary artist who was the color stylist of Disney’s One Hundred and One Dalmatians and headed up Hanna-Barbera’s background department for a time during the late-Sixties, passed away yesterday at the age 89. The news was first reported by Disney’s official D23 Twitter account, which misidentified Peregoy as an animator.

Born Alwyn Walter Peregoy in Los Angeles in 1925, and raised on a small island in San Francisco Bay, Peregoy often described his background as “American white trash.” As a teenager, he attended Saturday art classes at Chouinard Art Institute. He dropped out of high school in the tenth grade, and was hired at Disney at the age of 17 in the position of “traffic boy,” the lowest-rung employees at the studio who ferried artwork and supplies between offices. He quit after just a few months, saying that the studio felt too much like a factory, and wouldn’t return for another eight years.

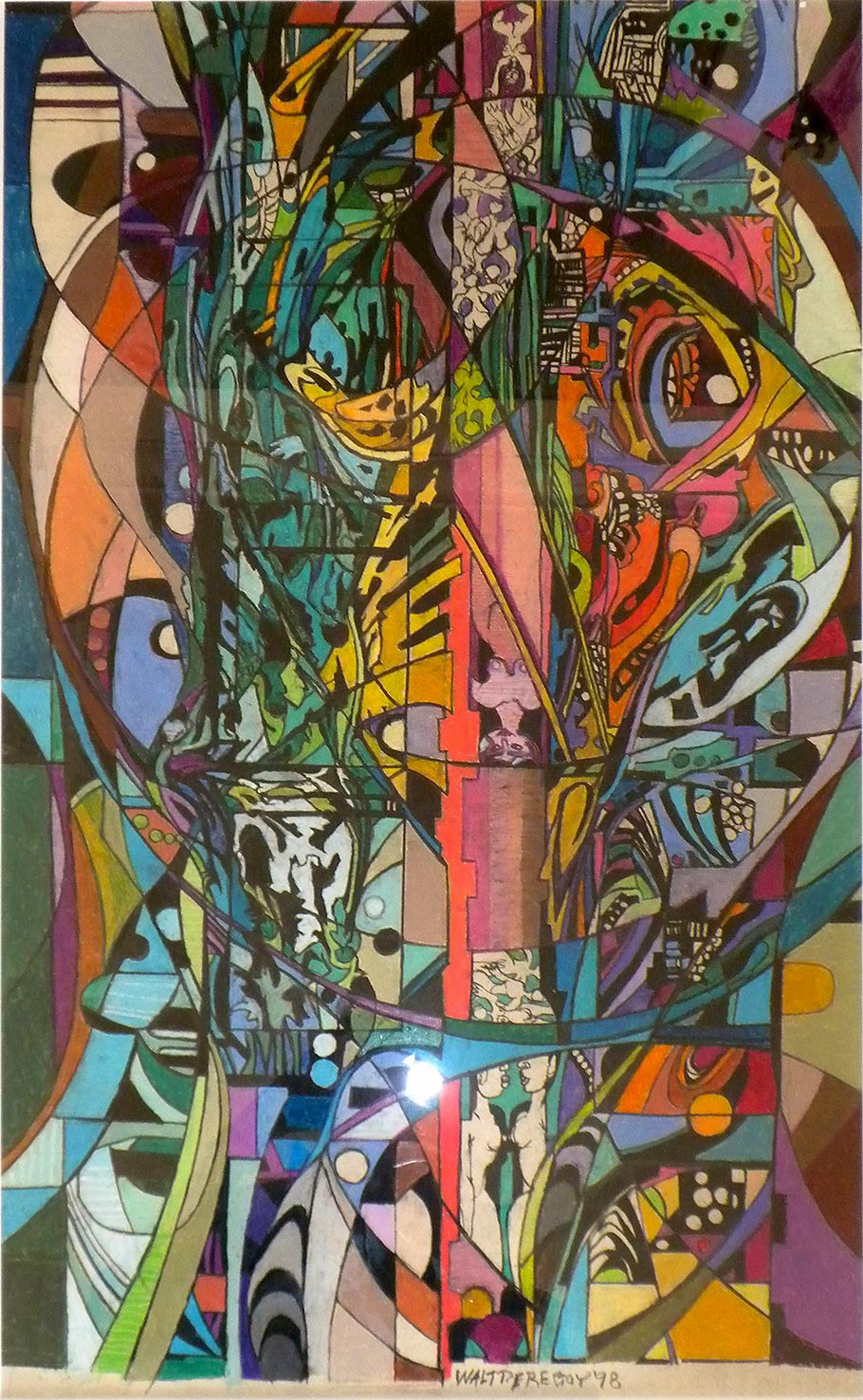

Following a short stint as a cowhand on the Irvine Ranch and a tour with the Coast Guard during World War II, Peregoy moved to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, where he studied painting and sculpture at the Escuela de Bellas Artes “under the influence of [David Alfaro] Siqueiros, Diego Rivera and [José Clemente] Orozco.” Later in the 1940s, he lived in Paris where he studied painting. A key influence on him at this time was the French painter Fernand Léger.

He was rehired at Disney in 1951 where “he started at the bottom again.” Peregoy worked for four years in the animation department as an inbetweener, assistant animator and clean-up artist, before production designer Eyvind Earle recruited him to become the first background painter on Sleeping Beauty in 1955.

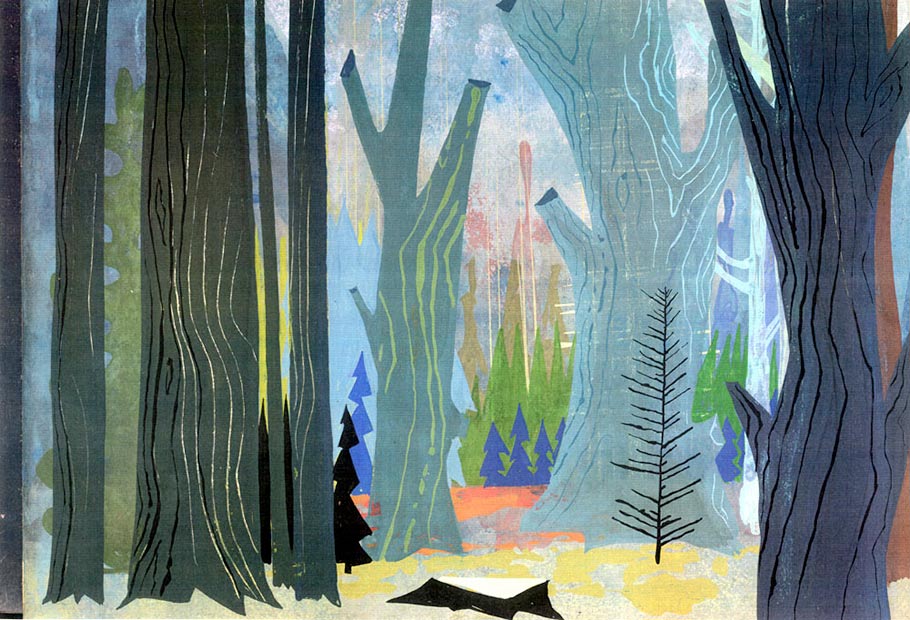

The studio’s next feature, One Hundred and One Dalmatians, was the project that allowed Peregoy to apply his fine art training on a Disney film. As the film’s color stylist, Peregoy worked closely with production designer Ken Anderson to devise a new way of painting backgrounds. With the background linework printed on a separate cel level (thanks to the innovation of the Xerography process) and overlaid on top of the painted artwork, Peregoy designed the paintings as broad flat areas of color “with the awareness that it was not necessary to go in and render the hell out of a doorknob, or a piece of glass, or a tree.”

“Peregoy in the 1950s was a true ‘Modernist’—a talented fine art painter who brought Modernism to Disney with strong abstractions in both layout and painting technique,” Pocahontas art director Michael Giaimo told me when I wrote the book Cartoon Modern: Style and Design in Fifties Animation. “His work was a purer abstraction of reality as opposed to, say, the beautifully designed but more grounded work of Eyvind Earle.”

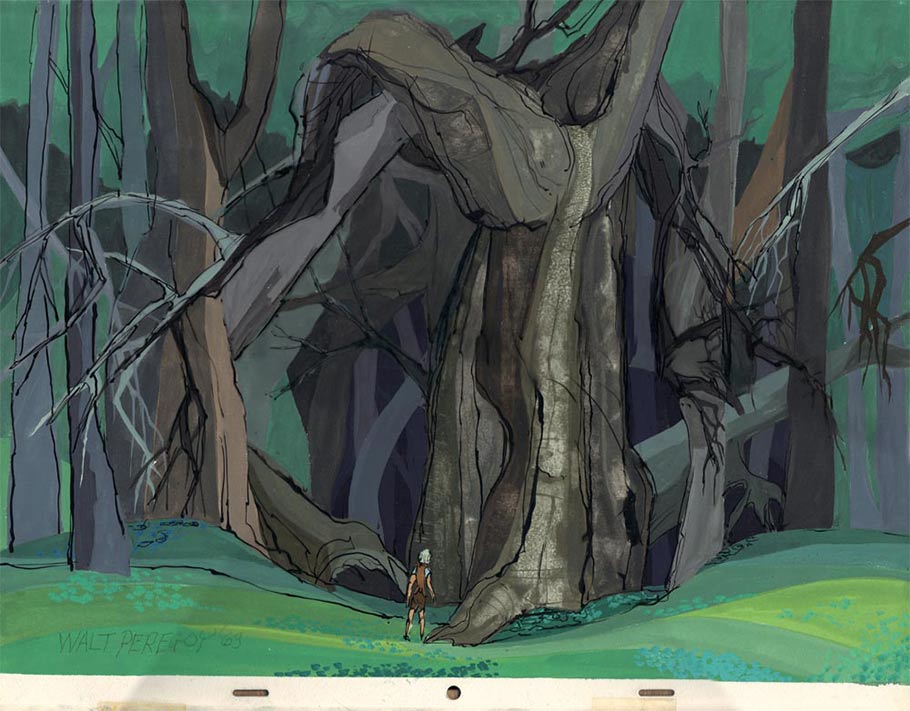

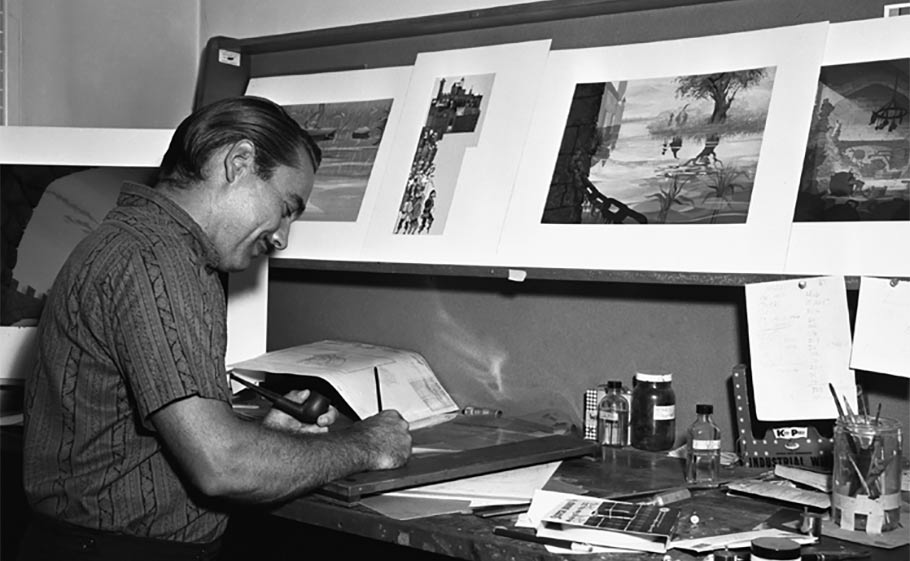

Peregoy made significant contributions to other films at Disney including Paul Bunyan, (1958), The Saga of Windwagon Smith (1961), The Sword in the Stone (1963), Mary Poppins (1964) and The Jungle Book (1967). While at Disney, he appeared in the famous Disney documentary 4 Artists Paint 1 Tree alongside artists Marc Davis, Eyvind Earle and Joshua Meador:

After being let go from the studio in the mid-Sixties, he started working in television on Format Film’s The Lone Ranger. On that show, he used a daring combination of grease pencil-on-cel with torn-construction paper underneath. Below, you can see a de-constructed background from the series that shows the grease pencil cel level and the separate color level underneath. “Powerful for Saturday morning, but you couldn’t say the backgrounds were Saturday morning crap because they weren’t,” Peregoy told interviewer Bob Miller.

His innovative work on The Lone Ranger led to being hired at the TV powerhouse Hanna-Barbera in 1968, where he headed the background department for five years. He either styled or supervised the background designs of The Perils of Penelope Pitstop, Scooby Doo Where Are You!, The New Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Dastardly and Muttley in Their Flying Machines, and Where’s Huddles?, among other series.

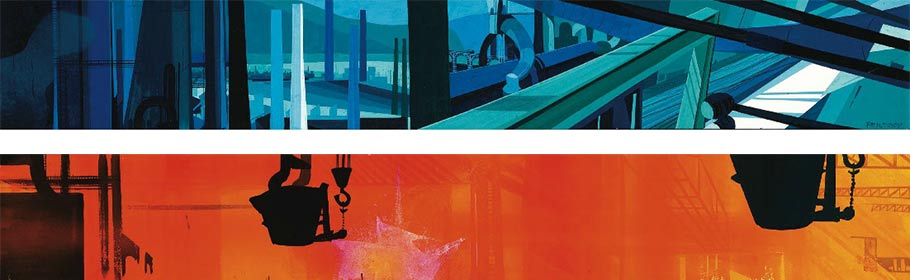

In the late-1970s, he returned to Disney’s theme park division WED, working on attractions for EPCOT such as Kraft’s The Land pavilion and Kodak’s Journey into Imagination. He continued freelancing in the animation industry during the Eighties and Nineties on projects that included My Little Pony: The Movie, Foofur, Tiny Toon Adventures, Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child, and The Specialists (below), a segment on MTV’s Liquid Television:

In later years, Peregoy was known as much for his colorful profanity-laced tirades against the industry as he was for his art. An interview with Peregoy (warning: very crude and offensive language) can be heard on the Animation Guild website. He was honored with an ASIFA-Hollywood Winsor McCay Award for lifetime achievement in 2012.

Below, a gallery of artwork by Peregoy: