Sue Nichols Maciorowski, Veteran Artist Of Modern Disney Films, Dies At 55

Sue Nichols Maciorowski, a veteran industry artist who played a pivotal role in the Disney resurgence of the 1990s, died from cancer on September 1. She was 55.

Nichols’s varied talents placed her at the heart of visual development at Disney. She helped design many of the studio’s most iconic characters and was also a prolific story artist. At a time when these parts of the production process at Disney were largely occupied by male artists, she managed to become one of a handful of women who had a voice in the early development of modern classics like Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Hercules, and Mulan. She also worked on Pixar’s Brave and STX Entertainment’s Uglydolls, among other projects.

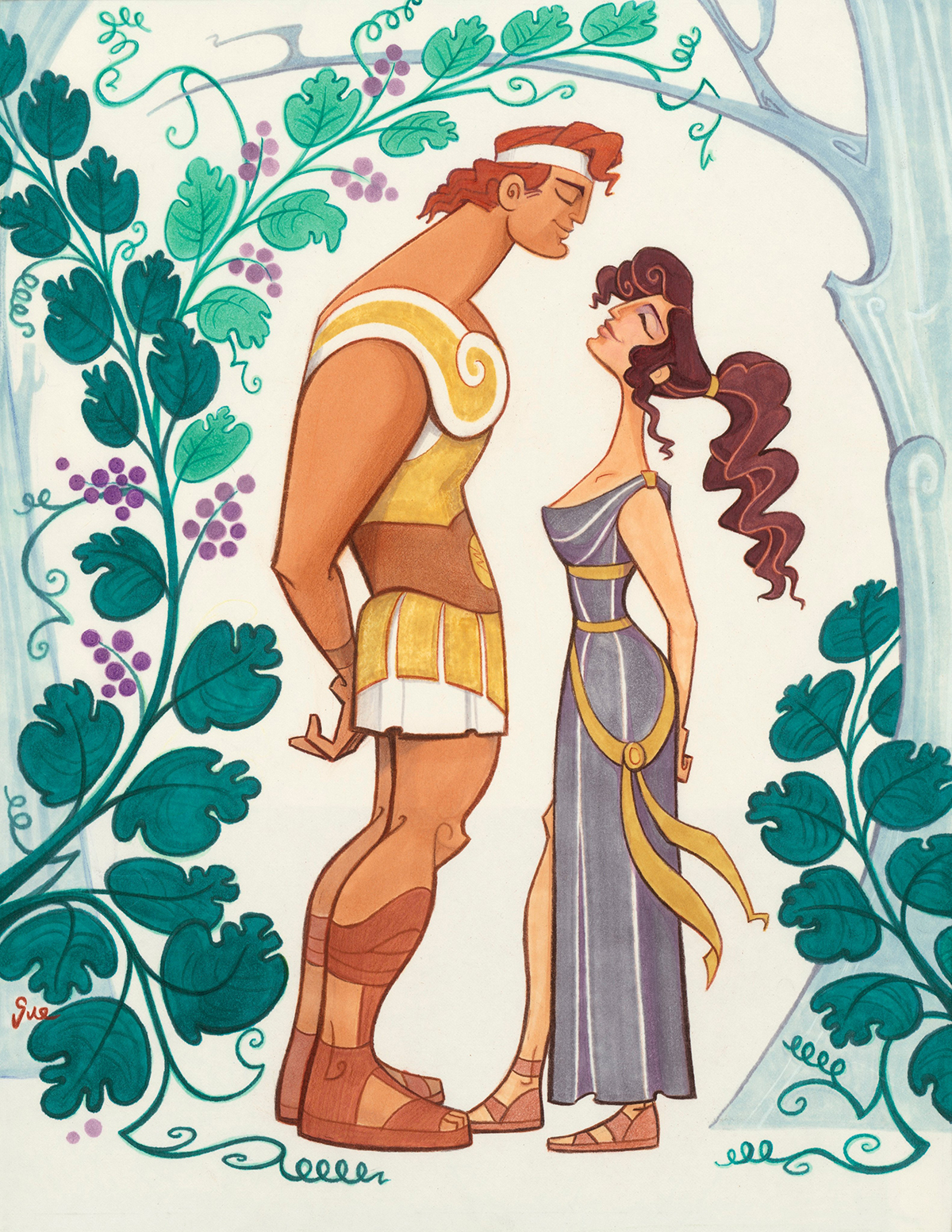

Among her creations, Nichols (the last name she used professionally) especially cherished the villains she developed, including Jafar in Aladdin, Frollo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Doctor Facilier in The Princess and the Frog. With her sharp eye and talent for research, she greatly influenced the production design of several Disney features: on Hercules, for instance, she created a style guide that determined the film’s reimagining of ancient Greek design. Her unique role on the production to help maintain consistency of style throughout the production process was acknowledged with a brand-new title: “production stylist.”

Susan Carol Nichols Maciorowski was born on June 10, 1965 and grew up in East Longmeadow, Massachusetts. She knew she wanted to be a Disney artist from the age of eight, and her passion for drawing led her to Calarts, from which she graduated in 1987 with a visual animation degree.

By then, Nichols had already done paid work on a number of industry productions, including as a model designer on My Little Pony and the Emmy-winning Marvel/Jim Henson series Muppet Babies. She stayed with the latter show after graduating, before moving on to a number of other small studios. “Building a solid reputation helps to keep you from being lost when entering a big company,” she later wrote about this phase of her career.

In her case, the big company was Disney, which Nichols joined shortly after it opened a dedicated development department. On her website, she described the department’s loose, experimental approach, whereby artists worked on multiple projects at once, many of which never saw the light of day.

After working on an animated intro to Cranium Command, an attraction at Disney’s Epcot park, Nichols was assigned to the development team on Aladdin, where she created early designs for the villain Jafar and came up with idea of the Genie as a shape-shifter. The feature also marked her first storyboarding credit. She worked thereafter on almost every 2d animated feature the studio produced in the 1990s, as well as many projects that never went past development.

Brenda Chapman, who worked at Disney with Nichols on films like Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King shared the following remembrance with Cartoon Brew:

There is so much to say about Sue. Her work was extraordinary. Her smile was bigger than life and infectious. Her mischievous sense of humor was pure joy to experience. Her kindness was ever present. I was over the moon when my best friend was hired at Disney, and we could work together for the first time on Beauty and the Beast. I will always cherish that time and those memories.

Over the years, although she contributed great design and story work to many films, Sue was too often overlooked when it came time for job title and credit. “The Grand Dame of Production Design” should have been one of her predominant legacies at Disney.

The animation industry has lost one of its greatest artists, but I have lost my best friend. Sue will live on in the brilliant work she left behind, and her bright smiling spirit will live on in my heart.

Others who have acknowledged her passing include animator Eric Goldberg, her longtime colleague, who said via the Walt Disney Animation Studios Twitter: “She will be sadly missed by those of us who had the good fortune to work with her, but her influence on those films will be there forever.”

Jorge Gutierrez, animator and director (The Book of Life), similarly praised her on Twitter: “Was lucky to attend her design class at Calarts. Profoundly talented and bursting with ideas and theories for designing character FOR character designs. Gracias, Maestra Nichols Maciorowski.”

Hercules marked a turning point in two ways. First, Nichols used computer software for the first time in her work, relishing its efficiency: “When, in story, ideas leave as fast as they come, your art has to be quick to keep up with the development.” Second, she exerted considerable influence on the film’s production design: as well as creating a style guide, she supervised the look across layout, animation, effects, color styling, and more, and even contributed drawings directly to the film. She would be called on to create style guides again for Atlantis: The Lost Empire and Lilo & Stitch.

As Disney’s 2d feature animation division was wound down, Nichols moved on to new technologies, new studios, and a new home. She directed a hybrid cg/live-action short used to test technology that would eventually be used on the feature Dinosaur; she noted that, technically, this made her the first female director at Walt Disney Feature Animation.

In 2002, she left her contracted position at Disney and moved back to Massachusetts, which remained her base for the rest of her life. She continued to freelance, working mostly remotely on several features for Disney, including Piglet’s Big Movie, Mulan II, The Princess and the Frog, Moana, and the live-action Enchanted, for which she designed costumes. She worked early on Pixar’s Brave and did storyboards on STX’s Uglydolls — her final film credit.

Outside animation, Nichols lectured about the industry and her place in it as a woman, and often helped out her community with free design work. She also wrote and illustrated books, including Occupational Therapy for Artists, an e-book of stretches and exercises. Work wasn’t always forthcoming, and in 2014 she took a day job answering phones. “Can’t be too snobby if you want to be an artist,” she reflected.

On her website, she described her career with humor and wisdom, doling out advice for those who would follow in her footsteps (guard against dodgy employers who don’t pay, remember that job titles impress executives, and so on). Her site is also a trove of sketches and other artwork from her career.

Nichols was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014, and tracked the progress of her illness in an online diary.

She is survived by her husband, Chester; parents Brian and Julie Nichols; siblings Mary Cole, Patricia Bleakney, and John Nichols; and two children, Stephanie and Jonathan.