Richard Williams (1933-2019), A Director, Animator, And Educator Who Pushed The Art Of Animation Forward

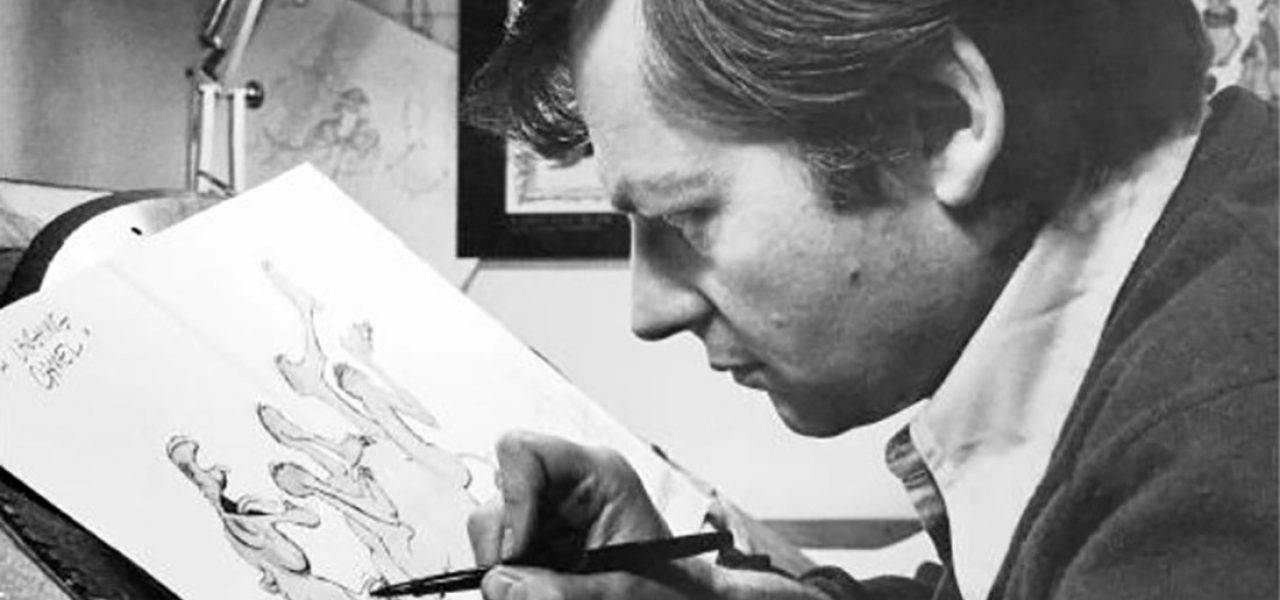

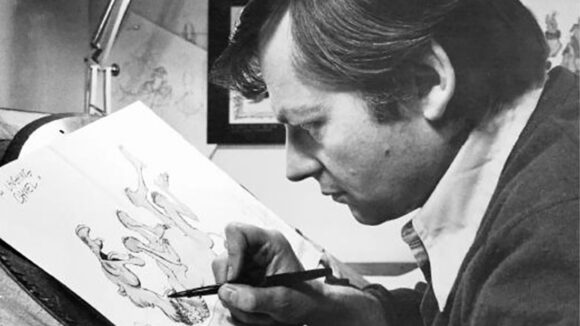

The animator and director Richard Williams died on Friday at his home in Bristol, U.K, after a battle with cancer. He was 86. His passing has prompted a torrent of tributes to his work in all its aspects: his skill as a draftsman, his innovation of the language of animation, his generosity as a mentor, his sheer longevity. As Cartoon Brew editor-in-chief Amid Amidi wrote in his reminiscences about Williams, it’s hard to know where to begin writing about such a varied, distinguished career.

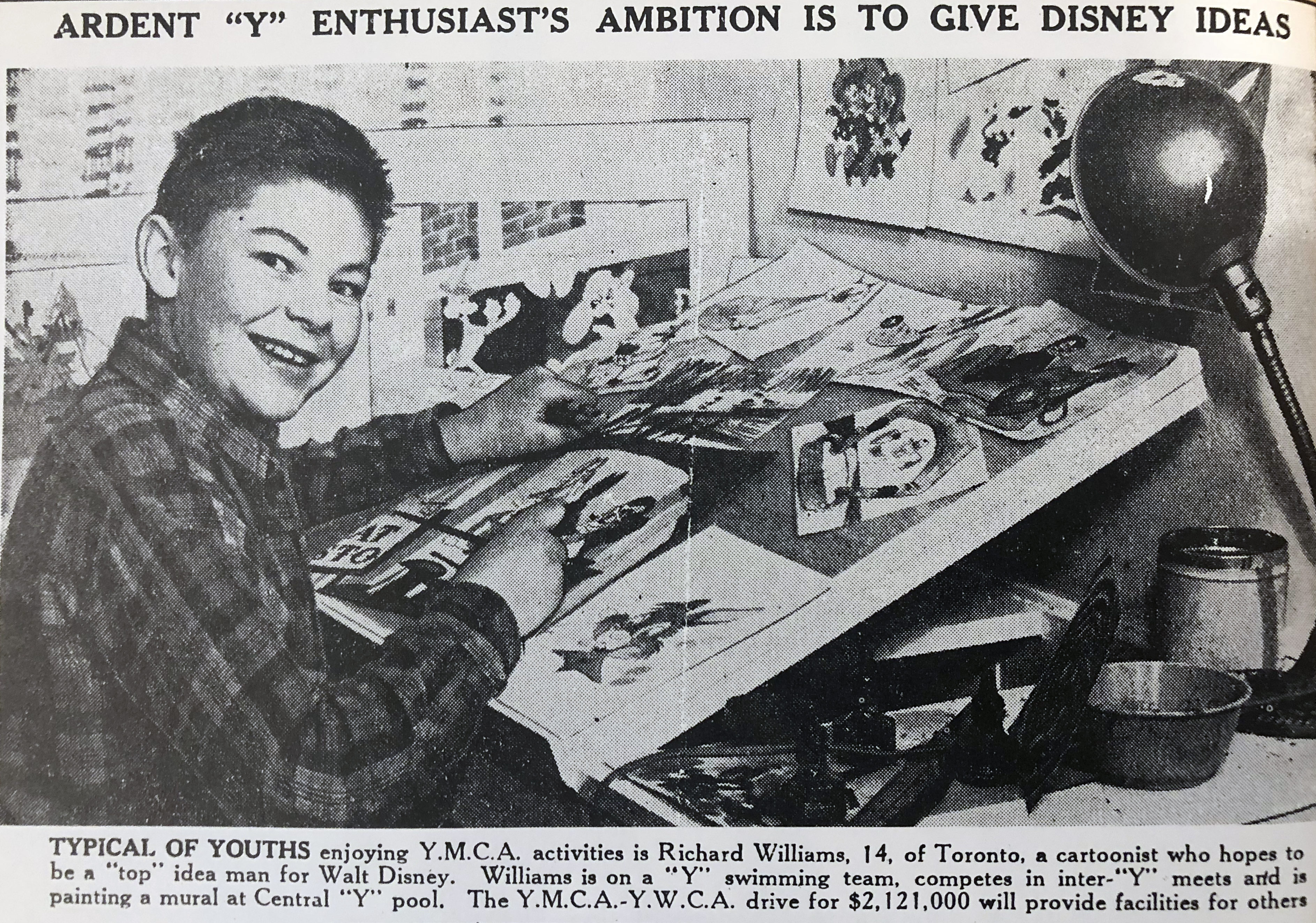

Richard Edmund Williams was born in Toronto on March 19, 1933. As a child, he was fascinated by Disney’s productions: in a 2016 interview at the Museum of Modern Art, he recalled that his mother — an illustrator who had turned down a job at Disney — once told him, “You saw Snow White when you were five, and you were never the same.”

Aged 15, he ran off to California to discover the studio for himself. He was keen to discover how its production pipeline worked, although he wasn’t interested in Uncle Walt himself, as “he didn’t draw.” As a publicity stunt, the company allowed Williams in for two days on the strength of his artwork, before art director Dick Kelsey told him to go off and “learn to draw.”

It wasn’t immediately to be. Williams claimed that he then “lost interest” in animation for some years, turning to fine art. He attributed his newfound interest in drawing and painting to seeing a show of Rembrandt paintings in Toronto. “I didn’t know anything about fine art, but I saw these Rembrandts and I went to pieces,” he told John Canemaker in a 1970s interview. “It made such an impact on me that I immediately dropped anything to do with animation or cartoons.” Following studies at the Ontario College of Art, he earned money from his illustrations and spent two years painting on the Spanish island of Ibiza, where he also played jazz. He was only drawn back to animation in his early 20s, because — as he told the BBC — “my paintings were trying to move.”

In the 1950s, by then disenchanted by Disney’s “sentimentality,” Williams moved to London. It was there that he established his animation career, using the modern cartoon styling that had been popularized by the UPA studio. His first short The Little Island (1958), in which three cartoonish humanoids engage in philosophical debate without speaking a word, won him a BAFTA (the British equivalent of an Academy Award). He wrote, produced, directed, animated, and financed the film himself.

Following the success of that short, he started working at the London commercial studio TV Cartoons, started by George Dunning. “It’s really a studio Dick Williams has had a lot to do with in the sense that he did a great deal to help in the early days to get it started,” Dunning once said.

Williams established his own studio in the early 1960s — Richard Williams Animated Films, Ltd. (later Richard Williams Studio) — and spent the following decades juggling commissions and personal work. His company swiftly became known for its very high technical standards; it was behind a run of lauded tv commercials and film titles like the Casino Royale and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.

His titles and animated interscenes for The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968), created in a labor-intensive editorial illustration style, drew new attention to his work and burnished his reputation for craftsmanship and quality.

He won his first Oscar for his 1971 adaptation of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, which was originally produced as a holiday special for ABC network. The film was executive produced by Looney Tunes director Chuck Jones, who once spoke of Williams’s quest for excellence: “[He] is a potential genius, but he will never be so in his own eyes. He will live and die in uncertainty. So there is great hope for him. We need more and more and more.”

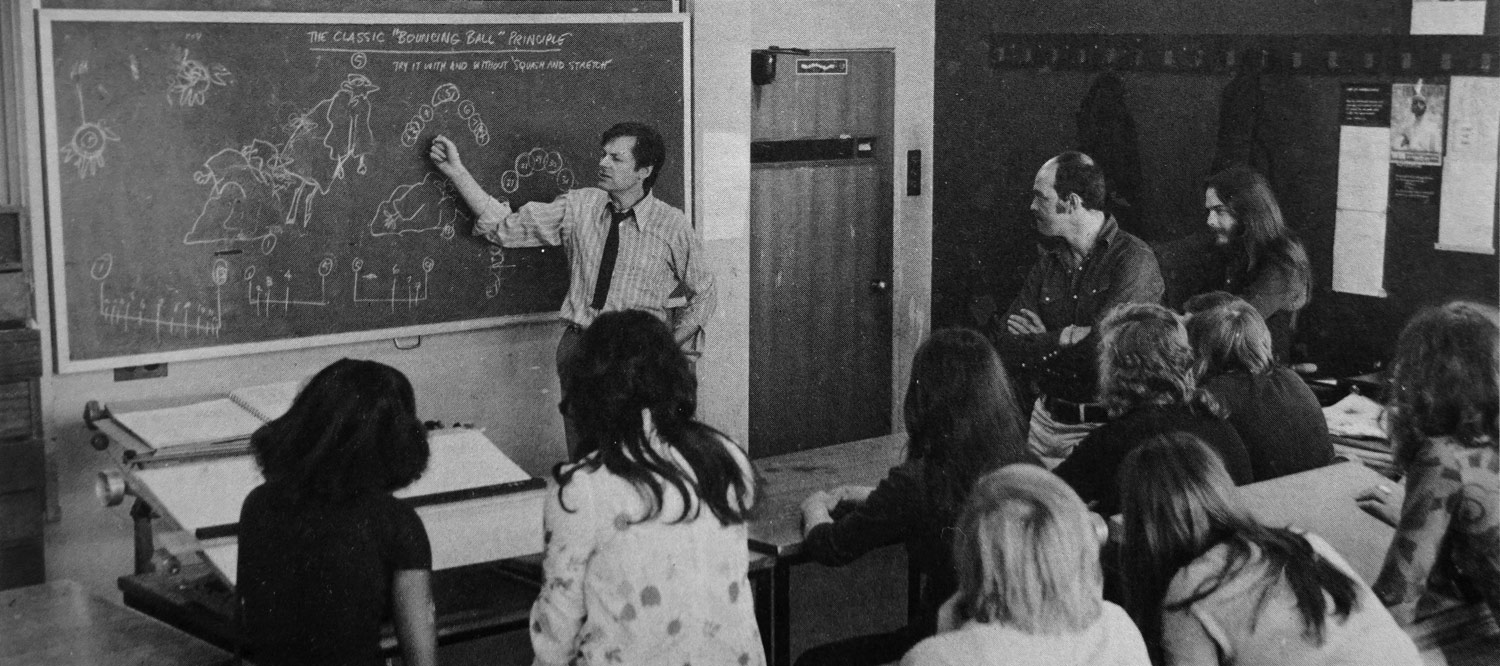

By this point he had started work on The Thief and the Cobbler, whose production would take on an almost mythical reputation over the years. Concurrent with the production of his own feature, which took place in between commercial jobs, Williams initiated an in-house training program at his studio to develop the skills of his employees.

As Williams himself recounted, the early 1970s marked a turning point in his animation career: “When we completed our work on The Charge of the Light Brigade we were a highly acclaimed animation studio, but I knew there were severe limitations to our individual ‘artistic’ and ‘stylistic’ approach. Flashy titles and tv commercials might make critics rave and might hold an audience’s attention for a few minutes, but they would not support characters and a story for, say, twenty minutes. And certainly not a feature-length cartoon.” For the next decade, Williams used his company’s profits to invite veteran industry animators, including Art Babbitt, Grim Natwick, Chuck Jones, John Hubley, and Ken Harris, to conduct workshops at his studio and sometimes work alongside his younger staff. The idea of launching an intensive training program at a mid-sized studio like Williams’s was unheard of then as it is now, but it is a reflection of Williams’s ultimate pursuit of knowledge and skill.

Williams had a chance to show audiences how far he’d come with his feature directorial debut, Raggedy Ann and Andy: A Musical Adventure (1977), an adaptation of the children’s book characters created by Johnny Gruelle. To make the film, Williams set up studios in both New York and Los Angeles, and put together an all-star team of industry veterans (Grim Natwick, Irv Spence, Gerry Chiniquy, Art Babbitt, Tissa David, Emery Hawkins, Warren Batchelder, Hal Ambro) and industry newcomers (Eric Goldberg, Dan Haskett, Sue Kroyer, Tom Sito, Michael Sporn).

The $4 million production was one of the most lavishly animated and visually inventive cartoon features of the 1970s, but it tanked at the box office and was criticized for its slow pacing and story. A representative opinion was Charles Champlin, who wrote in the L.A. Times: “Animation freaks are certain to take delight in the movie for the opportunities it has offered so many talented artists. At that it may have the episodic and accumulative nature of the project which worked against pace and exhilaration, and has provided a pretty and innocent children’s film falling well short of a classic.”

Williams followed that project with Ziggy’s Gift, an ABC holiday special in 1982 based on Tom Wilson’s newspaper comic. The project earned him an Emmy Award. In the mid-1980s, back in London, Williams embarked on what would become his most commercially successful and lauded achievement: directing the animation in Disney’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988). The Robert Zemeckis mock-noir comedy, a co-production between Disney and Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment, attempted something unprecedented: the seamless integration of 2d animation and live action. Williams was chosen over Disney’s own artists to oversee the animation. His work won him two Oscars — one for visual effects, and another special statuette for his animation direction and for creating new characters.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit was a triumph. However, as he would admit later in life, Williams only took it on to finance another feature. For decades, he worked on The Thief and the Cobbler, an immensely ambitious passion project inspired by the Arabian Nights. In the early 1990s, financiers took over the film and released it in bowdlerized versions — an experience that devastated the director. Although never finished in its intended form, the feature has more recently screened in a Williams-approved print, its animation displaying all the fluidity, visual extravagance, and dynamic staging for which he had become known.

With the success of Roger Rabbit and the collapse of The Thief behind him, Williams spent much of the 1990s touring the world with his masterclasses, while honing his life drawing skills. His teaching career culminated in the publication of his book The Animator’s Survival Kit (2001), which swiftly became an iconic reference work for students. More recently, Williams regularly fielded questions about animation as a craft and career on his Twitter account.

In his later years, Williams lived in Bristol, U.K., home of Aardman Animations (which provided Williams with his own studio space). His final film was the six-minute Prologue (2015), for which he received another Oscar nomination. Loosely based on Aristophanes’s anti-war play Lysistrata, it was entirely animated by Williams with pencil on paper — “the 3B system,” as he humorously described his lifelong commitment to hand-drawn techniques. The result is a stunningly virtuosic work which the animator regarded as his most accomplished, as he told Cartoon Brew in 2016. He hoped to develop the short into a feature, that he jokingly called, Will I Live To Finish This?

“A lot of [artists] do one kind of thing,” Williams said soon after the release of Prologue. “I wanted the whole whammy… I thought, ‘It doesn’t matter what I do. I’m going to master this damn thing, so I can really do anything I want.’ And I, fortunately, have achieved it.”

Williams is survived by his wife and longtime producer, Imogen Sutton; six children (Alexander Williams, Claire Williams, Timothy Williams, Holly Williams, Natasha Sutton Williams, Leif Sutton Williams); and seven grandchildren.

Plans for a public memorial have not been announced at this time.