Remembering British Animation Giants Harold Whitaker and Richard Taylor

Late last year, we lost two noted animation talents from the United Kingdom: Harold Whitaker (above, left) and Richard Taylor.

Early in his career, Harold Whitaker worked for the pioneering British cartoon director Anson Dyer; he was amongst the staff members of Dyer’s company to be hired by Halas & Batchelor, which was where he made his name. He contributed to many of the studio’s best-known productions: Animal Farm, Automania 2000, Foo-Foo, DoDo the Kid from Outer Space, Tales from Hoffnung (one short in this series, The Hoffnung Palm Court Orchestra, earned Whitaker a BAFTA nomination), parts of Heavy Metal (Grimaldi and So Beautiful and So Dangerous) and more. His other work includes providing key animation for TVC’s When the Wind Blows, and the 1981 book Timing for Animation.

Amongst Whitaker’s admirers in the animation community is Michael Sporn, who has blogged about him a number of times. In 2010 Whitaker was the subject of a BBC Gloucestershire article, which emphasised the local interest aspect of his career—one of Halas & Batchelor’s studios was based in the Gloucestershire town of Stroud, which was were Whitaker still resided after retirement. He passed away on Christmas Day at the age of 93 from kidney failure.

Richard Taylor began his career at the W.M. Larkin Studio, a protégé of the studio’s brilliant creative director Peter Sachs. After Sachs left in 1955, Taylor moved upward, first becoming the studio’s director of production, and in 1960, its executive director. At Larkins, Taylor directed heavily stylized industrial films such as Earth is a Battlefield (1957) and inventive theatrical commercials including “Put Una Money for There,” made for Barclays Bank branches in Africa.

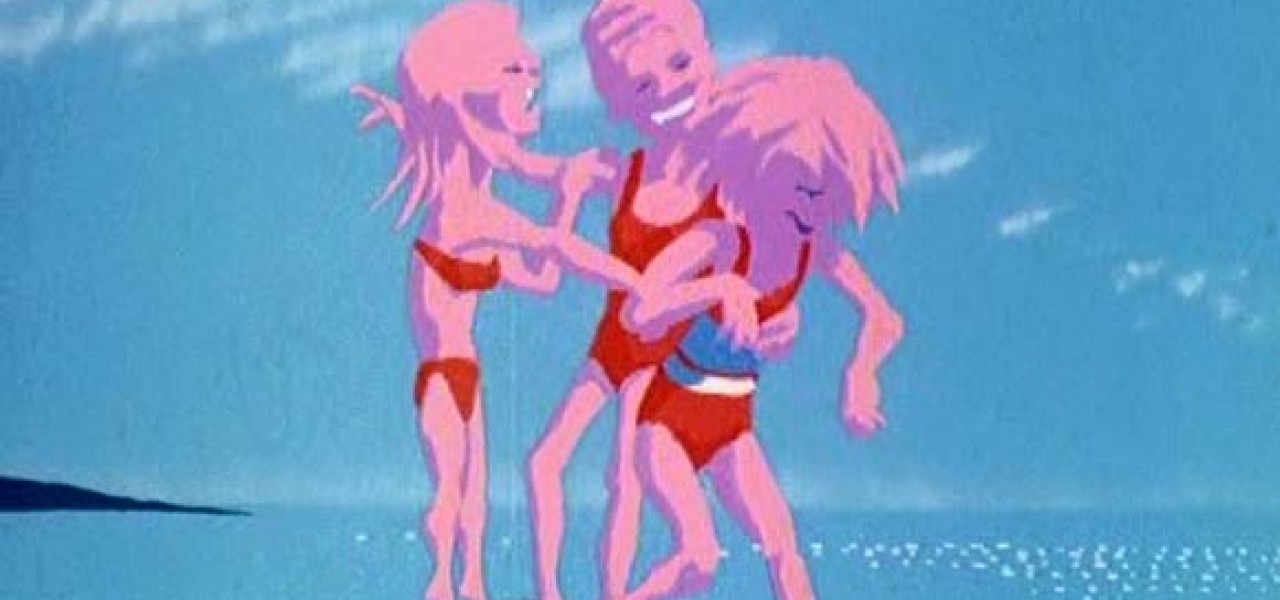

At his own studio Taylor Cartoons in the 1960s, he directed and animated entertainment shorts, among them Demonstration, Uhuru and The Revolution in the Sixties. He also animated Crystal Tipps and Alistair, a Seventies children’s series that remains a cult classic due to its funky designs. However, his main legacy lies in the dozens of public information films and educational shorts that he made from the Fifties to the Eighties.

Of these, it is the Charley series—widely known as Charley Says—that holds the firmest place in the British popular imagination, but these cut-out shorts about the everyday safety concerns faced by a boy and his cat are only the tip of the iceberg. Taylor had the natural ability to work in a range of styles, ensuring that his films remained entertaining while imparting their messages within limited budgets.

While encouraging children to swim in Swimsong, he used a bold style with no outlines and emphasis on rippling water. Elsewhere, he used inventive techniques to convey motorway fog and the dazzling that can be caused by car headlights. Even his work on Bill Stewart’s infamous Protect & Survive series—which Taylor acknowledged had a flawed premise—stands as a worthy example of infographic animation. In 1994, after retiring from animation, he imparted some of his experience in the book The Encyclopedia of Animation Techniques.

His daughter, Kitty Taylor, has written an obituary in which she provides a more personal look at the life and work of her father, who passed away last year at the age of 84.