Remembering An Animation Titan: Richard Williams

Director and animator Richard Williams died Friday evening at his home in Bristol, England. He was 86.

It is almost impossible to know where to begin writing an obituary about Williams, as no single individual has had as great an impact on the animation art form in the last fifty years as this Canadian-born artist. A full length obituary will follow this piece, but for the moment, I wanted to share a few off-the-cuff and rambling thoughts about Williams and his impact on our art form.

Williams animated for 74 years of his life. Here is the first animation he produced as a 12-year-old in 1945:

Richard Williams animated for 74 years. Here is the first animation that he ever made, age 12. pic.twitter.com/XKWoOe6ls0

— cartoonbrew.com (@cartoonbrew) August 17, 2019

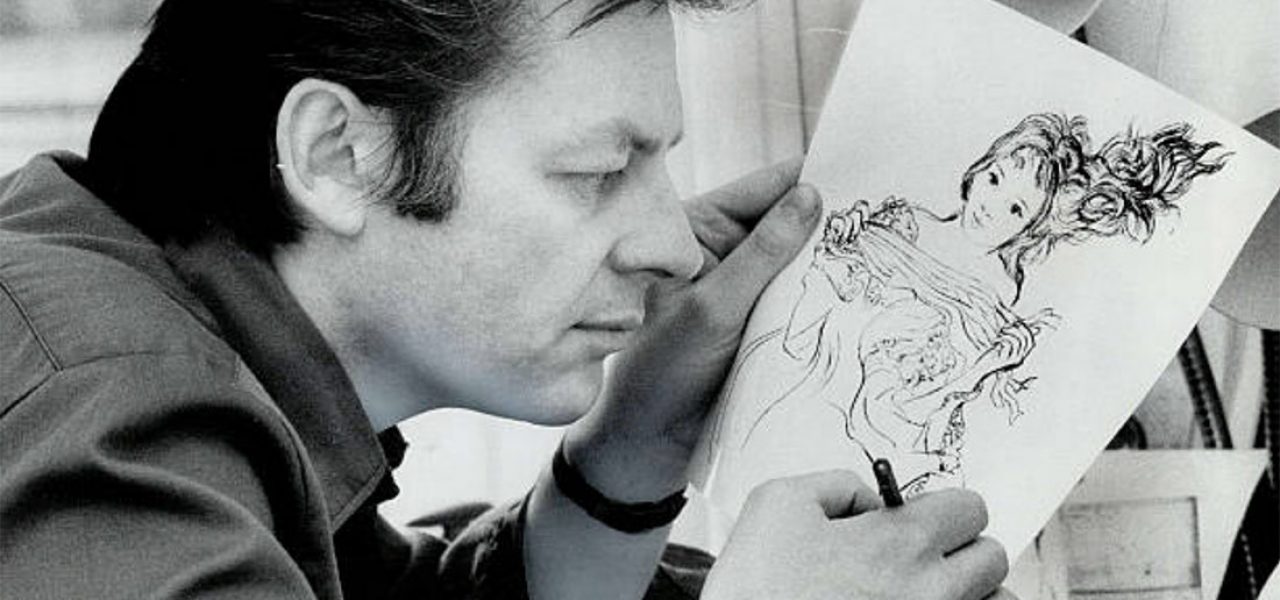

He was the encapsulation of the idea that life is a marathon, not a sprint. The documentary posted below from 1967 shows Williams as a successful 34-year-old commmercial filmmaker. By this point in his career, he’d won a BAFTA and he was running a successful commercial studio in London. For many, this would be a sign of having made it. But as Williams often reflected about this era in his journey, he really felt that he knew nothing about animation; he was just getting started.

For Williams, learning was not something that you did in your teens and twenties, and then started a career — it was a lifelong mission. It’s a journey that most don’t have the physical or mental wherewithal to pursue for as long as he did, and it’s both inspiring and intimidating to see someone who has accomplished so much before the age of 35, but whose work still doesn’t even approach what he would accomplish in the second half of his life.

I asked him a few years ago how he retained his skill level into his ninth decade. He attributed it to his continued study of life drawing. “It’s the hardest thing you can do,” he told me. “When you get out of it for six months and you go back in, you realize you’re a bum. That’s why people don’t go back to it. They say, ‘Oh, I did that in art school. We don’t do that anymore.’ And then you get stuck with cartoons.”

There are so many seminal accomplishments to write about from Williams’s career, but for my money, the most important one in terms of industry impact was his work as animation director of Who Framed Roger Rabbit. In today’s world, where almost every major film is a vfx spectacle or fully-animated film, it’s difficult to communicate how different the film landscape was in 1988 or what the phenomenal success of Roger Rabbit meant for animation. It was the film that put the wind into animation’s sails and swept us into this modern animation/vfx-driven era — its massive-for-the-time $350 million-plus worldwide gross awakened Hollywood to the idea that general audiences would accept animation in film if the storytelling was intelligent.

But Roger Rabbit very easily could have been a disaster in the hands of another animation director. The integration between animation and live action was more complex than anything that had ever been attempted up to that time, and pulling it off would require a caliber of skill that was uncommon in the late 1980s. Williams was one of, if not the only, animation director of the era who was capable of pulling off something as crazy and ambitious as what the film demanded, and his accomplishment did not go unnoticed. He not only shared the Academy Award for visual effects with other vfx artists, but won an additional special achievement Oscar for his animation direction.

Last year, when I moderated a talk with Williams at Annecy, I said something to the audience that I’ll repeat here: Williams is the only contemporary animator who, in my opinion, has built on the legacy of the classical Disney approach to character animation and added to what animators like Grim Natwick, Art Babbitt, Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston, Bill Tytla, Milt Kahl, and Marc Davis did a generation before him. He knew all of them, and worked with some of them closely. But he did not merely copy their principles. He expanded on their pioneering work, and evolved the art form to ever greater heights. His last short film, Prologue, released in 2015, is a graphic masterpiece that pushes his technical mastery further than he’d ever done before. As he told me back in 2015, “I’ve only just gotten to the point where I could marry my draftsmanship to the animation knowledge. It’s always been a battle for me.”

In fact, this may be Williams’ greatest legacy: setting a technical standard for the craft of hand-drawn animation. We know what’s possible and how we can build upon it in large part due to Williams’s single-handed dedication to pushing the craft’s limits and extending its boundaries.

What is equally remarkable about his career is that he set new standards regardless of what he was making. Artists tend to compartmentalize their work: This is a commercial job and I will only do what’s necessary to deliver on time and on budget; this is a personal project and I will make it beautiful. Not so with Williams. His standard always was excellence, regardless of whether he was producing a commercial, a tv special, a movie title, or an animated feature. There is never the feeling with his work that something was just a job or that it didn’t matter. It’s a remarkable ideal to uphold – to treat every piece of animation with the same dedication and commitment to craft. How do you do that for 60 years without burning out? I simply can’t imagine.

But here’s the trait that set apart Williams from other greats: his generosity. He was not selfish about what he had learned, nor did he believe that he was the chosen one or that only he could create this type of work. He wanted everyone around him to aspire to an exemplary level of craft. During his company’s heyday in London, his outfit was as much school as it was production studio. He invited countless animation greats to conduct workshops at his studio, and to work alongside and inspire the new generation of artists. After he closed his studio, he doubled down on his educational efforts, teaching masterclasses all over the world. Later, he compiled that knowledge into The Animator’s Survival Kit (2001), which in less than twenty years, has become an iconic reference book for anyone who aspires to create this standard of animation.

One of the great honors of my life was having the opportunity to moderate a talk with Williams last year at the Annecy animation festival. Here’s someone who had been at the very earliest editions of the festival, and yet he seemed as genuinely excited and energized to be at Annecy in 2018 as he probably was some fifty-some-odd years earlier. The night before our public talk, we had a three-hour dinner, and with a twinkle in his eye, he told stories that I’d never heard before. He knew that I was writing a book on Ward Kimball, and it was a surprise to me that he was just as enthused about hearing new tales about Kimball as he was talking about his own experiences. With Williams, one has the sense that animation was never really a career or job, it was a way of life, a religion, and until the end, he could never get enough of it.

There is so much more to say about his work and life. For now, let’s share some of the thoughts of the animation and film community who have been flooding social media with their tributes to Williams:

Richard Williams.

Damn, this one hit me. Everyone has their “Star Wars”, the film that blew their mind and forced them into filmmaking. Mine was/is Roger Rabbit.

I thank you, Mr. Williams…. on 1’s.https://t.co/X7bI61I5kU— Josh Cooley (@CooleyUrFaceOff) August 17, 2019

RIP legendary animator Richard Williams. The obituaries will (rightly) be full of references to Roger Rabbit and The Pink Panther, but my childhood memories are full of his brilliant adverts… pic.twitter.com/KBBuBej6NF

— Scarred for Life (@ScarredForLife2) August 17, 2019

A titan and true inspiration to me as a student and now as a teacher. RIP @RWAnimator https://t.co/EPTynxDMpr

— Elyse Kelly (@elysekelly) August 18, 2019

Today the entire animation community lost our teacher, Richard Williams. He was so impactful that every single animator owns his book. I never gone to an animator’s house and not seen the survival kit on their shelf.

Go watch people walk today – https://t.co/RZ4uJVyzsB

— April “Pinkie” Davis (@PinkieToons) August 17, 2019

On a sad day, it's uplifting to read the heartfelt tributes to Richard Williams from around the world. All I can add is: Thank you, Dick – for being my mentor, teacher, friend and inspiration for over 30 years. #RichardWilliams pic.twitter.com/MmtyKkYT09

— Neil Boyle (@TheLastBelle) August 17, 2019

RIP Richard Williams. #RIPRichardWilliams pic.twitter.com/P4XH7nh6H4

— Celia Bullwinkel (@Celiatoon) August 19, 2019

Really sad to hear about the passing of Richard Williams. His book, the animators survival kit, helped point me and a lot of young animators in the right direction. Rest in peace.

— Ross O'Donovan (@RubberNinja) August 17, 2019

If you haven't seen "The Thief and the Cobbler," seek it out and marvel at some of the most insanely fun and nuanced classical animation ever drawn on 1's…

The film was never properly completed, but the original scenes are jaw-dropping.#RIPRichardWilliams pic.twitter.com/MWFVVx1MDi

— Jim Zub (@JimZub) August 17, 2019

Richard Williams is and will still be a huge inspiration for many animators right now and animators in the futur.

I could learn so much thanks to his amazing book.So much passion, dedication and joy in his work, he will be missed.

Rest in peace and thank you for everything. pic.twitter.com/LedzDyQ21O

— Kéké 🥖 (@Kekeflipnote) August 17, 2019

old art but i cant believe i woke up to such sad news about Richard Williams, he had always been a huge inspiration for me ever since i watched Who Framed Roger Rabbit when i was little, which will remain my favorite movie of all time.

rest in peace, and thank you for everything. pic.twitter.com/EpIHOiiA89— Ami Guillén 🌱 (@lemonteaflower) August 17, 2019

Seeing so many beautiful tributes to #RichardWilliams today leaves me at a loss. A true master, he pushed the limits of animation and forced audiences to recognize our craft as the art form it is. He was an inspiration. https://t.co/KphnmVgCNN

— Lauren Faust (@Fyre_flye) August 17, 2019

I always loved this poster #RichardWilliams did for the @BFI LFF. In his book he wrote: “I meticulously painted this poster for the 1981 London Film Festival. Everybody said, 'Oh, I didn't know you did collage” pic.twitter.com/ECA313fI2g

— Matt Jones (@Jonezee99) August 18, 2019

Just woke up to the news that Richard Williams has left us. A huge guiding light for how we approach our art form and continue to redefine it. Let’s keep that spirit alive and continue to push things like never before, Ok, you guys? #RichardWilliams https://t.co/EAtmTXJO5n

— Scott Morse (@crazymorse) August 17, 2019

richard williams was without question one of the greatest visionaries in all of animation. his work not only set a standard that others could only hope to try and live up to, but also truly challenged and explored the capabilities of the medium as we know it. rest in peace dude. pic.twitter.com/pnKfugNXZ7

— justin m. morgan (@j_dubba_m) August 17, 2019

Richard Williams was and will always be an inspiration to generations of animators all over the world. His passion lives on. https://t.co/0nS9aqSnPk

— Nora Twomey (@nora877) August 17, 2019

Farewell master animator Richard Williams. These title sequences meant a lot to me as a child. They still do. https://t.co/0RVBIo6tD0

— edgarwright (@edgarwright) August 17, 2019

So sorry to hear of the passing of Richard Williams. He was one of the best and inspired so many. pic.twitter.com/IauRI3HkzM

— Aaron Blaise (@AaronBlaiseArt) August 17, 2019

Richard Williams was so kind to me and @chrizmillr when we met him in London this year. A legend who told us he was working on a new film and still drawing every day. @pramsey342 was star struck, muttering “the thief and the cobbler” RIP and thanks for all the inspiration. https://t.co/noR1IAJeVa

— philip lord (@philiplord) August 17, 2019

When people ask how anyone has the patience to do traditional animation, I show them pencil tests from the Thief and the Cobbler

On a technical level Richard Williams and the projects he helmed did more with pencils and paper than ought to be possible pic.twitter.com/PJ9HF0LT8C

— Akiel! 🌈 (@hereliesakiel) August 17, 2019

The animation industry lost a titan today. Richard Williams has had a profound effect on the art form. I’ve personally carried the wisdom from his books and appearances for decades in my career. Thank you Mr. Williams. R.I.P. pic.twitter.com/p5qEqmnkCp

— Everett Downing Jr. (@Mr_Scribbles) August 17, 2019

I am absolutely gutted. Without Richard Williams I don’t think my life would’ve ended up where it is today. He was beyond an inspiration. His work will live on infinitely. Rest In Peace and thank you for all you’ve contributed to the world of animation. @RWAnimator pic.twitter.com/rQpGfFnHqT

— Sabrina Alberghetti (@TheRealSibsy) August 17, 2019

I really can’t begin to express the inspiration and influence Richard Williams has had on me and so many other animators with his passion and vision for our art form . A true legend has passed.

— tomm moore (@tommmoore) August 17, 2019

This is true, Richard Williams democratized animation. I was a 14 yo in Chile without access to any classes but I was able to figure out a way to get the Survival Kit on Ebay for less than $30. Rest in peace and thanks for everything ✨ https://t.co/yRXxKg8wvk

— Fernanda Frick H. (@FernandaFrick) August 17, 2019

Rest in Peace Richard Williams….Master of animation, historian, and the single most important figure in recording & preserving the methods of animation to have ever lived. pic.twitter.com/dWw9uT0i8i

— Nick Kondo 近藤 (@NickTyson) August 17, 2019

Richard Williams set the bar so incredibly high for what Animation can/could be, and strived to keep working to perfect his craft up to the very end, which is the way all great artists leave this earth.

— Michael Ruocco (@AGuyWhoDraws) August 17, 2019

So sad to hear of Richard Williams passing. He seemed perpetually young & excited about life — fascinated by the capturing of it thru animation. I saw him last winter at a Bafta party, full of passion for life & the film he was working on. RIP

(His drawing of himself & Milt Kahl) pic.twitter.com/mTelje4KgT— Brad Bird (@BradBirdA113) August 17, 2019

richard williams was our michelangelo

— don hertzfeldt (@donhertzfeldt) August 17, 2019

RIP to a giant and true visionary of the medium. Thanks, Richard Williams. https://t.co/KidXbVhxPa

— Peter Ramsey (@pramsey342) August 17, 2019

From pink panthers and screwball rabbits to heroes trapped in intricate Escher-like worlds, Richard Williams’ uncompromising work spanned multiple genres and styles and was a testament to his utter devotion to the art of animation. There will never be another like him. RIP. pic.twitter.com/XCKBl9hxiI

— Shannon Tindle (@ShannonTindle_1) August 17, 2019

Very sad day for our industry. A major figure has passed away. @RWAnimator #RichardWilliams was & is an INDUSTRY GIANT. His worked inspired so many of us working & trying to break into this crazy business. His love for animation infectious #RIPRichardWilliams pic.twitter.com/ztaGRQBILl

— Jamaal Bradley (@JamaalBradley) August 17, 2019

The passing of Richard Williams is such a huge loss for the animation community. I don’t know a single student that doesn’t reference The Animator’s Survival Kit when first starting out; it may as well be a religious text. Rest in peace to a legend. pic.twitter.com/CWOMok2kY1

— Betsy Bauer (@bauerpower) August 17, 2019

A giant of our medium has left us. Once in a generation talent that changed what animation could be and how it was perceived forever. Thank you for all your wisdom and inspiration. A legend FOREVER. You left animation better than you found it. Gracias, maestro Richard Williams. https://t.co/KYErAmWt4G

— Jorge R. Gutierrez (@mexopolis) August 17, 2019

Rest in peace Richard Williams, I heard your voice everyday while I animated at school, and you have always helped keep me on the right track for animation. You have impacted so many lives with your animation techniques. https://t.co/n09BxxafX0

— Mii (@OrdanaVii) August 17, 2019

i never got the courage to say hello to him, but his talks, especially the one he gave for cobbler in london (during a special screening) was inspiring.. he really loved the medium, and i feel he made everyone in that room want to pick up a pencil and draw… rip master

— Paul Williams – ウィリアムズ ポール (@artporu) August 17, 2019

One of my favorite Richard Williams directed pieces of animation. There is so much joy and passion in his work. An inspiring reminder of how much there is to learn. https://t.co/Zc4pb7fbZt

— Adam Paloian (@adampaloian) August 17, 2019

Richard Williams

1933-2019 pic.twitter.com/jiGvvzis7p— Dave Alvarez (@DAlvarezStudio) August 17, 2019

In honor of Richard Williams, make your next shot something you've never done before. If you can, make it something no one's ever done before. It's up to us now. #RIPRichardWilliams

— Chris McCormick (@flatTangent) August 17, 2019