Ralph Eggleston, A Cornerstone Of Pixar’s Visual Style, Dies At 56

Ralph Eggleston, a cornerstone of the visual look of Pixar Animation Studios, has died at his home in San Rafael, California. He was 56, and the cause of death was pancreatic cancer.

The history of Eggleston’s career is also the history of the most revered contemporary U.S. animation studio. In an era when artists jump from studio to studio and project to project, Eggleston made Pixar his home for three decades and played a key role in defining the look and feel the studio’s films. More than that, he set the production design standard for depth and richness in visual storytelling at the studio, and his influence can be felt throughout the studio’s body of work.

Eggleston joined Pixar in 1993, at a time when few people had heard of the company. Director Andrew Stanton, who recruited him, spoke of the difficulty of finding someone to become the production designer of Toy Story, the first cg-animated feature produced:

When we got the green light for Toy Story and it became clear that we were really going to make the film, I started calling everybody I knew, saying, ‘You know how we used to always say there’s got to be a better way to make an animated movie? Well, we’re going to do it; come on up!’ But I think for many of them it was too much of a leap to make; cg was still too new and unfamiliar. Over the years, all the people I called eventually made their way up here one way or another. But the only person out of all those people I called that said yes right away was Ralph Eggleston, who came in to be our production designer. And thank goodness, because he really became a cornerstone of the look of our films.

When the end credits of Toy Story begin, Eggleston’s name is first listed. He is credited as art director, but he was also the film’s production designer, a credit that the studio hadn’t yet started using. Having never worked in cg before, Eggleston became responsible for the cohesive visual appearance of the 400 cg characters, props, and sets made for that film, providing detailed drawings and written notes to the fifteen or so modelers and technical directors.

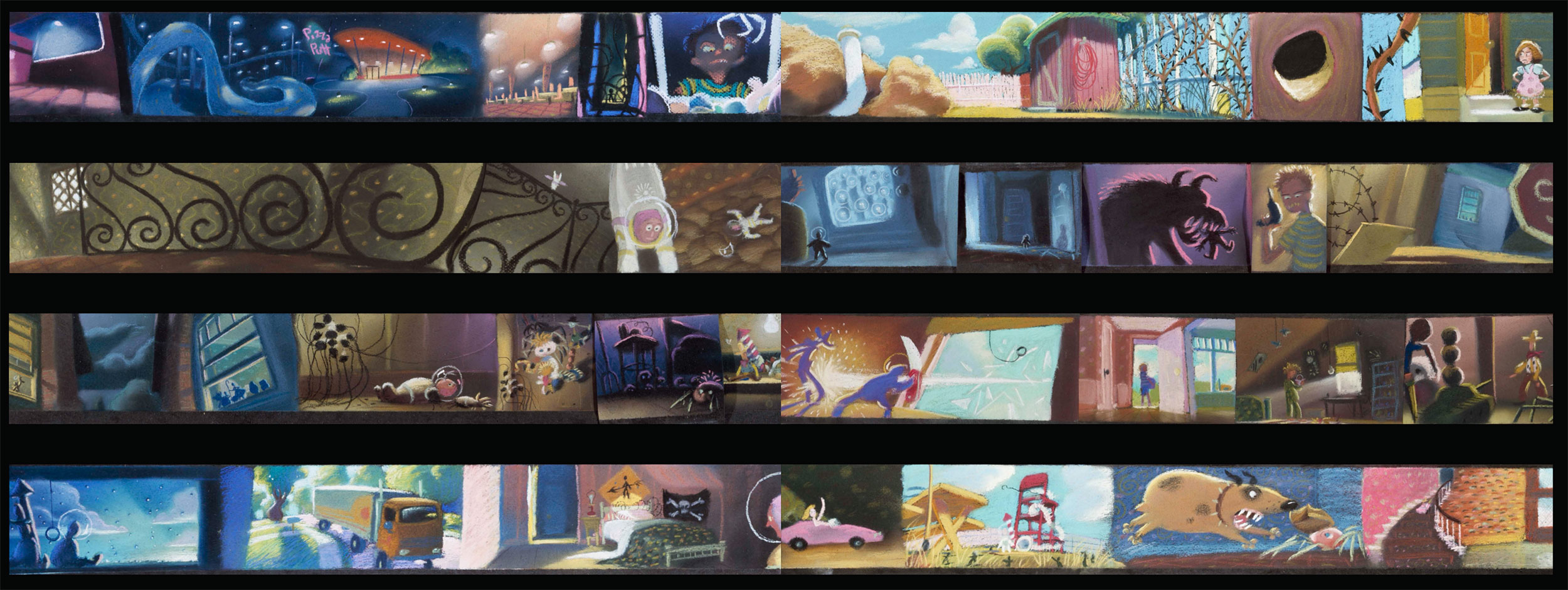

He did plenty of other work on the film, such as designing background layouts and creating the color script, a technique that he had first used when he was the art director of FernGully: The Last Rainforest (1992). Color scripts, he had discovered by accident, were an efficient way to convey color, light, emotion, and mood, as well as to give others on the production a sense of what the final picture would look like. When I was writing The Art of Pixar, Eggleston explained why he had first started using color scripts on FernGully:

There was a sequence at the end of [FernGully] and we had no time… there had been some embezzling going on and some other horrible stuff going on. But we had so little time to do this huge chunk of the movie, and we had 14 producers and it was just like a nightmare. And so to get [the producers] on the same page, an image was worth a million words. If I did a little quick pastel, they got it… move on. Or they didn’t like it and I would do another one. And in order to convey the entire sequence in one fell swoop… that was the only way I could do it, it was to do these little strips and kind of just block it out. I kind of hit my high point and my low point, what’s the story, and what are the characters and contrast and color and where did I want that to go. So when I started doing these strips [it allowed us to be] on the same page for this huge enormous sequence that was being done in different parts of the world. Once I did that, I was able to kind of take the layout drawings, give a chunk of the color script to the painter and with all the background paintings they knew exactly what to do within that – within a range of these colors, paint it like this. And then we could kind of farm it out that way and then adjust it later for contrast or color or specifics. And I literally stayed up one night, I actually did [the color script] in like… maybe two nights. I blasted through it, and it was almost like a stream of consciousness. It sounds so full of it, you know. Like method drawing.

Following Toy Story, Eggleston showed his versatility by helping to develop the story for Pete Docter’s Monsters, Inc. as well as directing the comedy short that would appear in front of the film, For the Birds. The latter film would go on to win numerous awards including the Annie award for animated short subject and the Oscar for animated short film.

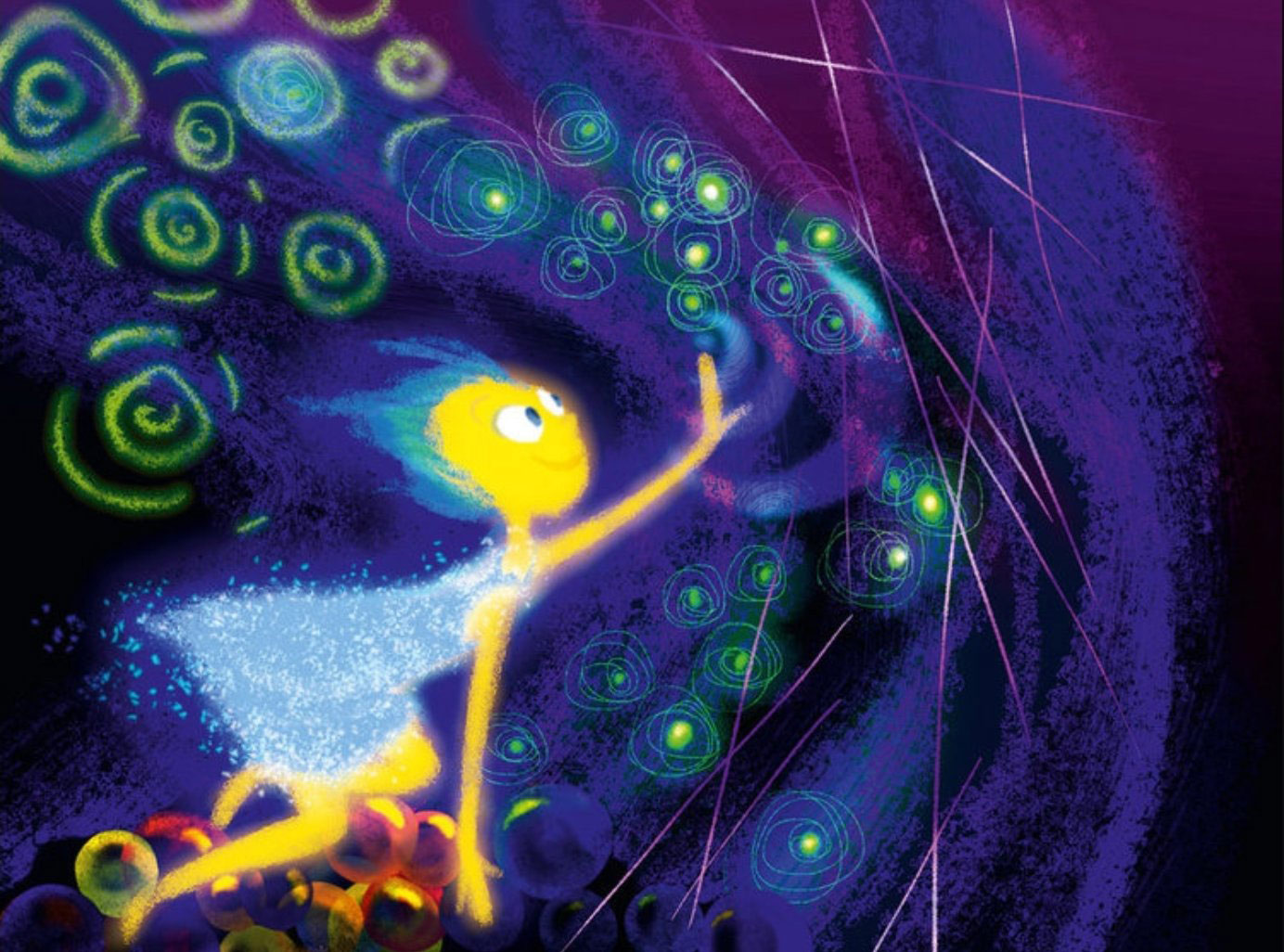

He was a workhorse at the studio and became the production designer of four other Pixar features – Finding Nemo, Wall-E, Inside Out, and Incredibles 2 – as well as an contributing art direction on The Incredibles, lighting direction on Up, lighting key design on Soul, and helping out on numerous other projects.

As a production designer, Eggleston approached the role with this mantra: “Start from the character and then everything else will follow.” It was his strict adherence to this principle that separated Eggleston from the pack and made him a venerated talent at Pixar, where storytelling is king. Brad Bird, speaking about Incredibles 2, gave an example of how Eggleston’s approach could complicate a production, yet also make the journey of the characters richer and more meaningful:

Ralph loves movies like most people at Pixar. He really loves films, and he’s always reading a new book, and he has a thing to show you. And he’s always disgorging art and books and things that he found and sketches he’s made. He’s just kind of spewing them out in every direction all the time. The film really benefited from this fuel.

The house that the family wound up in is a great example. He suddenly came in one day and we had already put a lot of effort in another house… and we were under a lot of pressure because they took a year off of our schedule. And he said, ‘Okay I have this idea for the house. And it’s really going to screw things up for everyone including me. But I just have to say it: the house should not work for them. It should be initially impressive, but then you get in there and everything is wrong for a family. There are these things that are beautiful originally, but they become like this problem. There’s no real place for the baby’s room: there’s a fireplace in the baby’s room for no reason.’ I’m listening to everything he’s saying. ‘That’s going to ruin everything; we’re gonna have to start again. But he’s totally right… and damn, why is he right?’ So I agreed to it. And it totally screwed up everything that I had set up. Suddenly everything was a giant problem. And yet, it was right because Ralph was right. The Parrs aren’t in a comfortable place yet. They have to find their way there. That was a way of making the surroundings help tell the story… which is really what good production design is.

Ralph Eggleston was born in Lake Charles, Louisiana on October 18, 1965. He graduated from Calarts in 1986.

Eggleston’s early pre-Pixar career was a grab bag of industry roles: character designs for Pound Puppies; animation on Garfield tv specials and Brad Bird’s “Family Dog” episode of Amazing Stories; film title designs for Hollywood Harry. “I always wanted to work at Disney, but I was never good enough,” he once said in an interview. “And so I kind of went around many places in the industry doing different jobs and before I knew it, I had a lot more experience than I anticipated or thought I would.”

No immediate information is available on surviving relatives.

Colleagues are remembering him around the internet, with one of the nicest tributes from James Baker, who recalled his first impressions of meeting Eggleston:

I first worked with Ralph in early 2000, on my first ever job working for Pixar, doing freelance visual development on what would become Finding Nemo. When I met Ralph, he was buzzing around like a caffeinated bee, talking a mile a minute, ping-ponging between subjects almost too fast for me me to follow. Given how much I came to love the man, it is funny now to remember that my very first impression of him was dread. On that first day, I was excited for the new gig, but feared that working for this coke fiend production designer dude was going to be an utter nightmare, and braced for the inevitable brouhaha.. I couldn’t have been more wrong, as working with Ralph was an absolute dream, and a major leap forward in my career. He encouraged me, inspired me, and pushed me to new levels without ever belittling as some creative leaders tend to do. I soon realized that his frenetic pace was not due to drugs, but simply the way Ralph’s mind naturally operated; at top speed, on about 150 channels at once.

Some other tributes from industry colleagues:

when other people disregarded them. He had a crazy sense of humor which I always appreciated. He was a man of unlimited energy, sometimes to his own detriment. My buddy once said working with Ralph was like trying to herd a bag full of cats…

— Neil Blevins (@ArtOfSoulburn) August 29, 2022

The animation world has lost a giant today. Ralph Eggleston will be remembered not only for his immense contributions to the art form (incalculable) but for who he was as a person. pic.twitter.com/MMj7MeD2t7

— Josh Holtsclaw (@joshholtsclaw) August 29, 2022

RIP Raph Eggleston. Truly one of a kind. His massive talent was matched only by his kindness. 💔 pic.twitter.com/GkD5Tt5X9B

— Angus MacLane (@AngusMacLane) August 29, 2022

Ugh. So fucking sad. Ralph Eggleston was such a inspiration. I reached out to him on my first AD gig for some advice about color and story. He shared his wisdom & time and gave me the confidence to trust myself. I’ve always cherished that! Gonna miss him. ❤️

— Dave BLEICH (@dbleich) August 29, 2022

Ralph Eggleston – you will be missed forever. Working with you was always the absolute best. ❤️❤️❤️ Also, fuck cancer. pic.twitter.com/asyFczehyb

— Oren Jacob (@orenjacob) August 29, 2022