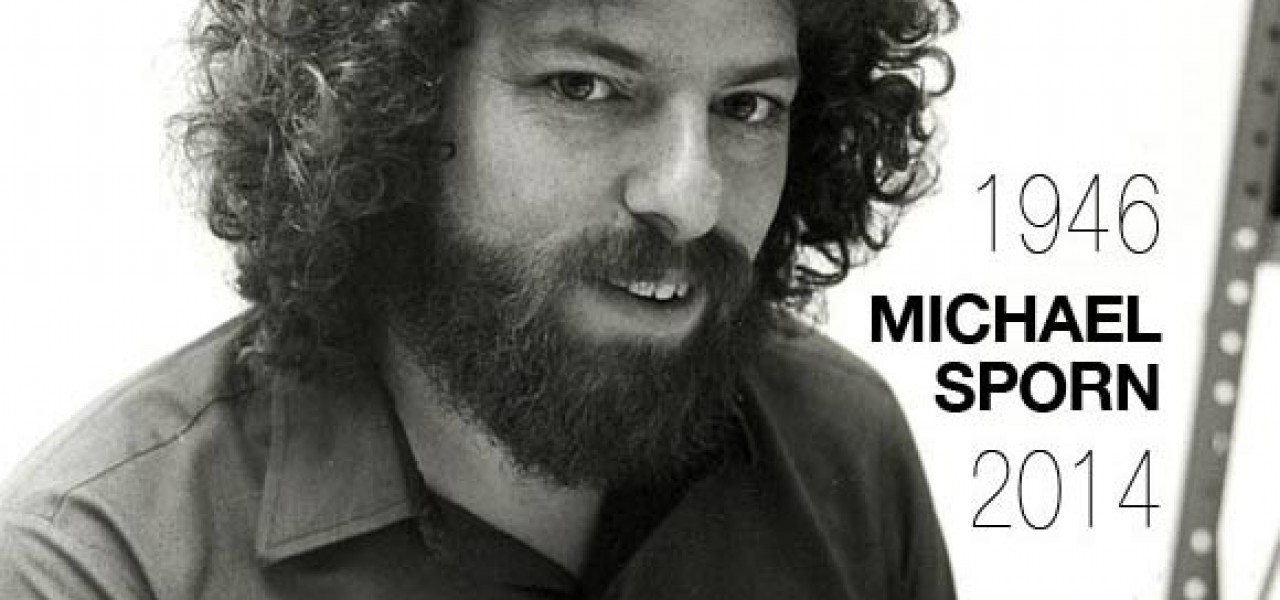

Michael Sporn, A Passionate Film Director, RIP

Animator and filmmaker Michael Sporn, a man who represented the spirit and vitality of New York’s animation scene as much as any other single individual, passed away from pancreatic cancer on January 19. He was 67.

Michael started his career working with some of the animation industry’s biggest names—John and Faith Hubley, Richard Williams, R. O. Blechman—before setting out on his own. Working with small budgets and a fine-tuned sense of personal aesthetics, he directed dozens of singular short films, TV specials and children’s book adaptations, and received an Oscar nomination for his adaptation of William Steig’s Doctor De Soto (1984).

Michael Victor Sporn was born in New York City on April 23, 1946, and grew up in Jackson Heights. Sporn had the cartooning bug “right from the beginning,” he told historian and friend John Canemaker in an unpublished interview. He taught himself animation with the materials that were available in the 1950s, including Preston Blair’s famous book and the how-to segments that appeared in the the 1950s TV series Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color and The Woody Woodpecker Show.

At the age of 11, he bought a used movie camera with tips that he earned from delivering medications for the local pharmacy. He, then, purchased a projector, and began collecting 8mm cartoons and live-action short subjects. “I jiggered the projector to maneuver the framing device which allowed me to see one frame of the film at a time, so that I could advance the frames one at a time,” he wrote. “I could study animation. [Ub Iwerks’] Jack and the Beanstalk and Sinbad the Sailor were the first films I’d bought and watch endlessly over and over frame by frame. In short time, I knew every frame of Jack and the Beanstalk backwards and forwards. I didn’t realize that it was Grim Natwick who had animated (and directed the animation) on a good part of the film. Meeting Natwick years later, I think I surprised him by saying as much. He just moved on to another subject, appropriately enough.”

Sporn earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts at the New York Institute of Technology, and afterward enlisted in the US Navy serving as a Russian language decoder in Alaska. While serving in the Navy in 1970, Sporn wrote a letter to the Disney studio in Los Angeles asking for advice about working in the animation industry. “I have been very interested in animation for quite some time and hope to someday gain a position as animator. I have geared my education toward this goal by majoring in Fine Art at college and receiving a BFA degree. I have spent many hours reading about the field and many more hours in making amateur films.” He went on to write that “despite the reading I’ve done in the past I know little of what to expect in the first few months.” In the letter, he wondered about the best way to acquire a position in the industry and questioned whether it would be better to move to Los Angeles for greater work opportunities.

The animation industry was experiencing a deep slump at the time, and jobs (and worthwhile projects) were few and far between. Disney director and animator Ward Kimball responded to Sporn, advising him to take a cinematography course and find experience or training in a studio setting. Kimball concluded the letter by asking, “Have you considered something more solid as a career? Like dairy farming?,” a line that Sporn enjoyed recounting years later.

Sporn didn’t move West and started his professional career in New York City working for independent filmmakers John and Faith Hubley. Among the projects he contributed to were the short Cockaboody (1973); The Adventures of Letterman series for the 1971-77 PBS series The Electric Company; and the TV special Everybody Rides the Carousel (1975). Sporn considered working with the Hubleys “one of the high spots of my life. It was all that it could have been and more.”

Next, Sporn served as the assistant animation supervisor of the Richard Williams feature Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical Adventure (1977). “He’d been thrown into the deep end of the pool on that, for sure,” recalled veteran artist Dan Haskett in an online comment. “Yet he ran interference for a large group of nervous apprentices, and did it with grace, knowledge, and an unfailing wit.”

Disney animator and director Eric Goldberg, who started his career on the film, wrote, “Mike was my first real ‘boss’ on my first real job. I learned a lot from Mike in my formative years, and I truly appreciate the confidence he had in me…I was always struck by his knowledge, generosity of spirit, and passion for the art, craft, and medium of animation.”

In the late-Seventies, Sporn also worked at R.O. Blechman’s The Ink Tank studio, where he supervised numerous TV commercials and served as assistant director of the PBS special Simple Gifts (1977).

Sporn formed his own production company, Michael Sporn Animation, Inc., in 1980 where he avoided lucrative advertising gigs in favor of doing short films, including many adaptations of children’s books. John Canemaker summarized some of the highlights in an obituary notice he wrote:

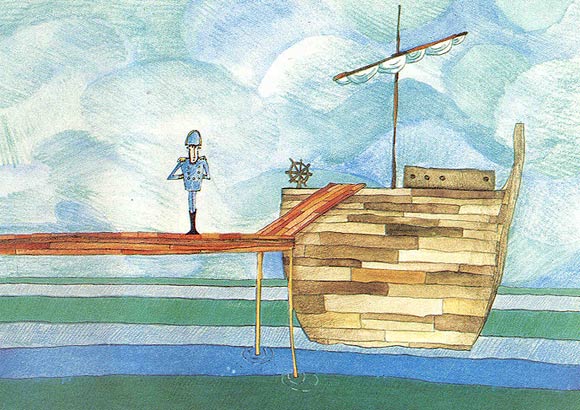

Michael Sporn earned a 1984 Academy Award nomination for the short film Doctor De Soto, adapted from William Steig’s children’s book. It was one of fifteen short children’s films Sporn produced and directed for distributor Weston Woods, including Steig’s Abel’s Island (1988), which was nominated for an Emmy Award; The Amazing Bone (1985), winner of a CINE Golden Eagle; and The Man Who Walked Between the Towers (2005), winner of the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Children’s Video and Best Short Children’s Film award from the Ottawa International Animation Festival.

Sporn’s animated HBO specials adapted from children’s books and tales include: Lyle Lyle Crocodile (1987); The Red Shoes (1989); Mike Mulligan and His Steamshovel (1990); The Marzipan Pig (1990); Ira Sleeps Over (1992, CableACE Award winner); Goodnight Moon and Other Stories (1999, Emmy winner); Happy to Be Nappy and Other Tales (2006); Whitewash (1995, Emmy winner); I Can Be President (2011).

Sporn’s studio served as a training ground for many artists entering the industry in the Eighties and Nineties. Ray Kosarin, who animated on over a dozen of Sporn’s films, remembered what is was like to work for him:

Working with Michael was exhilarating. His love of the films made you love them too. His studio atmosphere was perfectionism checked by humility: your work had better be good, but not conspicuous about it. Michael’s direction was firm but also intuitive and, wonderfully, open-minded. He’d hand out full sequences, casting animators according to their sensibility, and if you wanted to do a particular sequence, he almost always made sure you got it, apparently trusting there was probably a good reason it spoke to you. He made clear what he felt most at stake in the story but seldom gave too-specific directions, preferring to watch where your instincts carried the scene. When busy on a production, Michael moved swiftly and spoke little, which sharpened you to the small but critical signals whether you were giving him what he wanted. When OK’ing a line test of a scene you’d just animated, he might offer half a grin and say, “It moves,” then get on with something else. (It was some small comfort that that’s also what he usually said when reviewing a scene he’d just animated.) But when you gave him something he really liked, he’d often just say, “Great.” At least you were pretty sure that’s what he said. But he said it quickly, while already striding away toward his desk: no time for an end-zone dance. When the studio was humming, it felt like a large family, all cooking dinner.

Mark Mayerson, who also animated on some of the studio’s films, wrote about Sporn’s principled creative stance in which his artistic freedom and working on projects that mattered to him took priority over all else, including the lure of bigger budgets:

The animation I did for him had to be on three’s in order to stay within the budget. Working for cable channels or PBS, it was a given that budgets would not be as high as those from the networks. However, the freedom these outlets provided allowed Michael to make films that he cared about. The Red Shoes, Happy to be Nappy and Whitewash all dealt with race. The Little Match Girl dealt with urban poverty. Abel’s Island, based on a book by William Steig, dealt with loneliness and the power of art. That film and other Steig adaptations, Dr. Desoto and The Amazing Bone, are far more faithful to Steig’s work than DreamWorks was.

In addition to commissioned works, Sporn produced personal films such as his droll adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark, and the hard-edged but uplifting Champagne (1996), which is a personal favorite of mine. Narrated by a teenage girl who at the age of four had witnessed her mother killing a man, the sensitivity and humanity of Michael’s animation and direction elevates it above the typical narration-driven animated film into a powerful and poignant work of art.

Sporn also created dozens of spots for Sesame Street such as this one:

His studio created titles and inserts for live-action features including Prince of the City (1981), Garbo Talks (1984), and Desperately Seeking Susan (1985), and interactive elements for the Broadway musicals Woman of the Year (1981) and Meet Me in St. Louis (1989). At the time of his death, Sporn producing and directing Poe, an animated feature based the life of Edgar Allan Poe.

When an artist dies, there is often regret in not having recorded their views on the art form. Fortunately, in Michael’s case, he leaves us with a remarkable legacy in the form of his online journal/blog which he updated daily since 2005. Filled with thousands of posts, the blog is a treasure trove of artwork from his own career, rare historic materials from his personal collection and the collections of his friends, personal thoughts, and observations about the animation industry past and present. An insomniac, Michael worked on the blog in the wee hours of the morning, often scanning in dozens of images for a single post, not to mention creating pencil tests of the drawings. The blog expressed his unmitigated love for the art form, and his desire for artists to push themselves to not create junk and instead use animation to tell stories that matter. That was what he personally did throughout his career. The blog remains one of the most valuable resources on the Internet for aspiring animators and a lasting testament to his spirit of generosity.

Sporn is survived by his wife, Broadway singer and actress Heidi Stallings; his sisters Patricia Sherf and Christine O’Neill; and brothers Jerry Rosco and John Rosco.

On a personal note, I first began corresponding with Michael in 2003 when I started working on the book that would become Cartoon Modern. We had many back-and-forth correspondences in which he shared his vast knowledge about the New York animation scene, but his generosity went far beyond that. When I wanted to come to New York for the first time in 2004 to do research for the book, he offered the use of an empty apartment he had for as long as I needed. It was an unexpected gesture that meant far more to me than he could imagine, and allowed me the luxury of spending two weeks in New York, something that I otherwise would not have been able to afford on my meager finances at the time. That experience was what made me fall in love with the city, and eventually move here, and for that, I will always be grateful to him.

A few years afterward, when I won an award for Cartoon Modern, Michael showed up at the ceremony like a proud parent. After the show, he and John Canemaker treated me to dinner. The friendship and support of Sporn and Canemaker, artists whom I respect and admire so much, meant as much as the award itself.

It’s those individual gestures and acts that can never be properly accounted in an obituary. Michael’s time on this planet impacted the lives of others in big ways and small—through his actions and through his art—and for that we are infinitely richer.