Ken Mundie, Adventurous Artist Who Pushed Graphic Boundaries In Hollywood Animation, Dies At 97

Ken Mundie, a graphic artist with an expressive illustration style who forged his own path in the Hollywood animation industry, died of natural causes on April 3, 2023. He was 97.

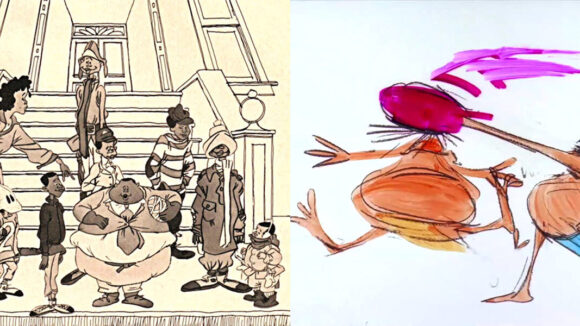

Mundie was a one-of-a-kind artist who bridged mainstream-indie line for years. Among his best-known credits are the Fat Albert television special Hey, Hey, Hey, It’s Fat Albert (1969), which was entirely different from the Filmation series that followed, and the outré short The Door, which scored distribution by Warner Bros. in 1968.

Mundie was born on October 7, 1925, in Los Angeles, California. He spent the first part of his life in Detroit, but when the Great Depression hit, his family relocated to Virginia to live with his grandparents. His father was a house painter and, according to Mundie’s obituary, a moonshiner during prohibition. It was Mundie’s father’s illicit second career that compelled the family to move back to Detroit in 1931, when the Virginia authorities made it clear that the moonshiner was no longer welcome there.

In 1942, at the age of 17, Mundie enlisted in the United States Marine Corps. He was stationed in San Diego and served in the South Pacific. He later used the GI Bill to enroll in art school in California, where he studied under Elwood James Fordham and Mentor Huebner.

Early in his career, Mundie was accepted to the Disney trainee program, though it’s unclear how long he spent at the company or what productions he worked on. According to his family, in the 1950s Mundie worked as an illustrator for The Washington Post, did freelance animation for various studios, and worked as an artist for North American Aviation. The earliest confirmed screen credit that we could track down for Mundie was the 1959 teenage road safety film Stop Driving Us Crazy, produced by Washington D.C.’s Creative Arts Studios.

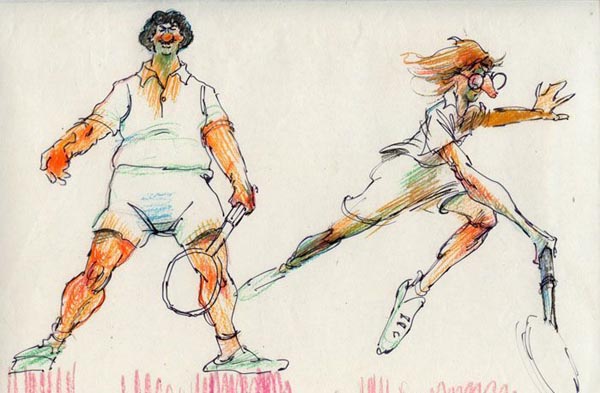

Mundie’s career flourished in the 1960s. It’s not that all the projects he was involved with were hugely successful, although some definitely were, but Mundie was able to lock down consistent work using his own personal illustration style, which was rooted in anatomical figure drawing and far removed from animation character design tropes.

From 1964-1966, Mundie worked at DePatie-Freleng Enterprises as a background painter on theatrical shorts including the Pink Panther series. Studio head Friz Freleng also employed Mundie to design title sequences in his own style for several major Hollywood films like The Trouble with Angels (1966):

Mundie illustrated the brilliant opening sequence to Blake Edwards’ The Great Race (1965):

His work can be seen in the opening credits for the final season of the iconic Clint Eastwood series Rawhide:

As well as another classic western series, The Wild Wild West:

In 1968, one of Mundie’s best-known works, The Door, scored a release from Warner Bros. The eccentric short, which Mundie made entirely by himself, was produced by Bill Cosby’s production company Silver-Campbell-Cosby Corporation. Mixing animation and live-action stock footage, the anti-war short is a pure expression of Mundie’s visual style, with his rough gestural figures appearing to have been drawn in grease pencil directly onto cels.

Working with Cosby once again, Mundie directed the tv special Hey, Hey, Hey, It’s Fat Albert in 1969. The program aired on NBC on November 12, 1969, and was rebroadcast twice after that, but has unfortunately never been released onto home media and is incredibly difficult to find today. A copy is held at The Paley Center for Media in New York City, but online only a few brief clips have surfaced.

Vastly different aesthetically and tonally than the later tv series, the pilot was a real artistic statement. Mundie and his team of animators worked 18-hour days for six months to meet NBC’s deadline, drawing on cels with grease pencils and coloring each cel themselves. Those cels were then photographed, with live-action footage from Philadelphia used for backgrounds.

Veteran Disney animator Will Finn has written about the short in the past, saying:

Visually, it may be one of the most experimental and offbeat cartoons ever run on a major network. Director Ken Mundie and his band of independent animators make a point of rendering each scene with as much spontaneity as possible, almost no single movement is animated, timed, or assisted conventionally or formulaically. One very unique choice was that the characters’ faces are less exploited than are their highly expressive figures. The poses and proportions are remarkably gestural and adapted loosely as possible for whatever purpose fits… More than just about any piece I could name, this 26-minute film embraces the possibilities of xeroxing animators’ roughest drawings and capturing them at their most vital.

The Fat Albert pilot’s eventual erasure by NBC (or more likely, Cosby himself) is a good metaphor for Mundie’s larger animation career. His adventurous spirit and personal style never meshed well with the norms of an industry that thrives on formulas and standardization, yet this also means that his earlier work was truly unique and deserves to be reevaluated today. He was a natural illustrator and fine artist who was able to bend that skillset and apply it to the commercial opportunities that came his way, making the projects in which he was involved all the more special.

Later in his career, Mundie regularly worked as a storyboard artist, frequently in advertising. He spent time at the Leo Burnett ad agency in Chicago and also worked at Hanna-Barbera. Even at a company like Hanna-Barbera, which had strictly circumscribed house styles and production pipelines, Mundie managed to sneak in his distinctive characters, such as in this musical sequence he directed for the series Yogi’s Galaxy Goofs-Ups:

In the 1980s, he did development work for the Japanese feature film Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland.

According to his obituary, Mundie “slowed down” in semi-retirement in the 1990s by contributing storyboards to numerous animated series including Pinky and the Brain and Life with Louie. He was also hired by Wallace Creative Inc. to work on cut scenes for the 1997 video game Captain Claw, which featured an impressive mix of 2d and cg animation that felt revolutionary at the time.

Wallace Creative founder Donald Wallace said of Mundie in an interview:

I hired additional artists/animators for the project. One gentleman was a veteran Disney animator who was semi-retired and living in Idaho. He and I would have story discussions over the phone and then he would send me art and animation through the mail, except for a couple times when he traveled to Portland and worked in the studio with us. He was amazing. I think he was in his late sixties at that time but could work tirelessly and for very long hours. Between the two of us, we created all the storyboard panels. He was an excellent storyboard artist. He had an incredible sense for layout and storytelling, and I had a lot of fun working with him.

Mundie’s obituary explained that:

To him, art was a kind of magic, and it frustrated him when people didn’t appreciate that. He loved talking to and helping other artists. From painting classes to introductory animation courses, he believed his knowledge and experience were meant to be shared.

Mundie is survived by his wife, Delores; his son, Morgan; his sister, Hazel Crljenko; his nieces, Sally (Greg) Hands and Nancy (George) Kelbley; and his nephew, John (Susan) Crljenko.

Picutred at top: Hey, Hey, Hey, It’s Fat Albert; The Door