Juan Padrón, Cuban Animation Legend, Dies At 73

A morbid week for the industry continues with the news of yet another death: that of Juan Padrón, arguably the most important figure in the history of Cuban animation. Padrón died on March 24 after being hospitalized for three weeks with a respiratory illness. (Speculation that Padrón had coronavirus were discounted by his son who has said online that the tests for coronavirus were negative.)

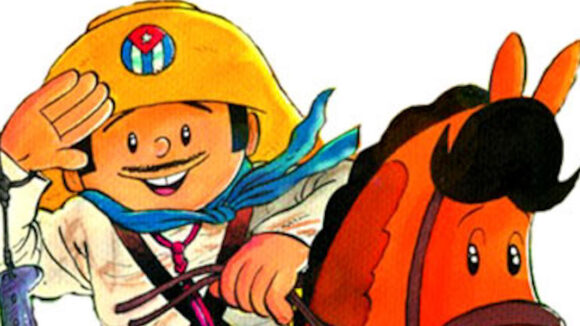

As a filmmaker and cartoonist, Padrón created works and characters — notably the liberation fighter Elpidio Valdés (image at top) — that have transcended their mediums to enter the Cuban popular imagination. He spearheaded many changes in the way animation is made in his country. His status there is comparable to that of Walt Disney in the U.S. or Hergé in the Francophone world.

Born on January 29, 1947 at Carolina Sugar Mills in the Matanzas province of Cuba, Padrón started his career in 1963 as an animator for Cuban state tv. He served as an assistant to Harry Reade, an Australian who had moved to Cuba, drawn by its revolutionary ideals. Together they made the short film Viva papi! (Long Live Daddy!, 1963; remade in 1982).

Padrón acknowledged Reade’s influence on his creative development:

He taught me a lot about scriptwriting and the need to work hard in improving my drawings; to study classic novels and films; that culture is also learning to do things with your hands; to learn from the farmers and very poor people; to learn to call trees by their [given] names.

Padrón also worked for the film section of the Cuba army. Meanwhile, he was making a name for himself as a cartoonist, drawing strips for a range of Cuban publications. Like his later films, many of these were disseminated widely across Latin America and the Soviet Union.

In 1970, the artist launched his most famous creation, Elpidio Valdés, a machete-wielding, horse-riding mambí colonel pitted against Spanish colonists in the 19th century. The charismatic character, who consistently outwits his enemies in the fight for his homeland, proved a hit with readers young and old.

Around this time, the Cuban government began to take a special interest in animation as a vehicle for family entertainment. Funding for the sector was distributed under the auspices of the ICAIC, the national film institute. Among the beneficiaries was Padrón, who was commissioned to bring Valdés to the screen.

He directed a number of shorts about the fighter throughout the 1970s, infusing them with his own historical research. “If I’m making [a film] about a past epoch, I’d like it to be true to life,” he said. The series would eventually comprise some 30 shorts and three features, the first of which — simply titled Elpidio Valdés (1979) — was the country’s first ever animated feature.

Another feature came in 1985: Vampires in Havana told the story of a professor who develops a potion to protects vampires against the sun, only to find that dastardly vampires from the U.S. and Europe want to steal it. The film proved very popular at home and something of a cult hit abroad (it can be streamed on Amazon). Two decades later, Padrón directed a sequel, More Vampires in Havana.

The director struck a more adult tone in his contributions to Filminutos, a long-running show he helped launch which consists of minute-long vignettes, and Quinoscopios, a series of shorts based on the drawings of the Argentine humorist Joaquín “Quino” Lavado.

Cuba’s film industry was hit hard by the collapse of the Soviet Union, and Padrón’s output slowed from the 1990s. While occasionally directing films — including for overseas producers in Spain and elsewhere — he increasingly toured Europe and Latin America as a lecturer and festival guest (the video below was taken during his 2017 visit to the Havana Film Festival New York).

In his homeland, he remained an active teacher and important figurehead in the arts. At the time of his death, he was working to establish La Manigua, a center in Havana aimed at promoting his work and Cuban culture in general.

Padrón’s death has been met with a deluge of praise across Latin America and beyond. Simón Wilches-Castro, the Colombia-born creative director at Titmouse, studied under Padrón, and has written a tribute for Cartoon Brew. Comments from other artists, journalists, and family members are copied beneath.

When I was a kid I used to watch a videotape my father had filled with some cartoons called Quinoscopios: animated vignettes adapting the work of Quino, the world-renowned Argentinian cartoonist. Years later I caught a broadcast of Vampires in Habana on Colombian public tv. The film looked like a crooked version of a Hanna-Barbera cartoon. It was weird, violent, and had nudity in it. There was no internet at the time to look it up, so it took me years to realize both these pieces were the work of the same man: Juan Padrón.

In 2008, I got an email inviting me to apply to the first animation course being taught at the San Antonio de Los Baños film school in Cuba. The course was gonna be led by Padrón, so I didn’t hesitate to apply, despite the forecast of Hurricane Ike being en route to hit the island during the time of the course.

Because life in Cuba is such a unique experience, it is difficult to describe what meeting and hanging out with Padrón was like. In Cuba, Padrón had the same cultural influence of Walt Disney in the U.S. But we got to ride to school with him every day on a ramshackle bus because his car had recently broken down, and the parts to fix it were almost impossible to acquire.

Padrón was kind, charismatic, and a natural-born storyteller. The bus rides with him were filled with anecdotes from his time in the military, his experience as an animator in Cuba, and his trips to Russia, Spain, and even the U.S. He was a historian and a comedian at heart and you can see both these passions come out in his Elpidio Valdés shorts, where he retells the story of the Cuban independence campaign but filled with all the gags you would find in a Looney Tunes cartoon.

Padrón told me that when he graduated school there were no animation jobs to apply to, and most of his classmates held out waiting for the perfect job to appear. Instead, he applied, if I remember correctly, as a designer at a shoe company, confident that his talent would make somebody realize that he could be better used as an animation artist than a shoemaker. And indeed it did.

This is the biggest lesson I remember from my time studying under Padrón, and in a way, it perfectly represents the Cuban and the Latin American spirit. Never wait for things to be perfect because they might never be. But trust your passion and be relentless and you might end up where you were meant to be.

We feel deep sadness at the passing of our friend, the uniquely talented Cuban animator Juan Padron. He created timeless work, like “Vampiros en la Habana” and much more.

He animated the video for "A Thousand Million Reasons:" https://t.co/c1LZUjKenJ

— Colin Hay (@ColinHay) March 24, 2020

Sad news. A true master of the form, Juan Padrón's style established and formed the look of Cuban animation for generations. A few years back, the Havana Film Festival in NY held a reception for him and displayed paintings of his beloved characters. I was lucky to meet him then🇨🇺 https://t.co/4YKwTGE64Q

— Monica Castillo (@mcastimovies) March 24, 2020

Saddened by the passing of iconic Cuban animator Juan Padrón, a legend who directed features like VAMPIROS EN LA HABANA (its sequel MÁS VAMPIROS EN LA HABANA), ELPIDIO VALDÉS, & MAFALDA. I remember scouring Mexico City for a copy of his films. Descanse en paz, maestro. 🇨🇺 pic.twitter.com/sQwsgox7iw

— Carlos Aguilar (@Carlos_Film) March 24, 2020

Buf, qué mal. El mismo día que Uderzo ha muerto Juan Padrón. Excelente dibujante, acojonante animador, currela incansable, divertidísimo conversador y, encima, muy majete. pic.twitter.com/KKsOvNmN1K

— Mauro Entrialgo (@Tyrexito) March 24, 2020

Cuban animator and director Juan Padrón passed away yesterday at age 73. I spent last night watching his amazing 1985 film VAMPIRES IN HAVANA. If you're a fan of independent adult animation, watch it on @PrimeVideo. It's a $1.99 rental and absolutely worth checking out. Q.E.P.D. pic.twitter.com/PqRX9cNo0P

— Ted Geoghegan (@tedgeoghegan) March 25, 2020