From Teeny Little Super Guys To Animated Dogs: Paul Fierlinger Dies At 89

Award-winning independent animator Paul Fierlinger, fondly remembered by the general public for his Sesame Street work, passed away at age 89 on Friday, April 4, 2025.

Known for his warm, reflective style and a career that straddled both commercial and personal storytelling, Fierlinger lived a life shaped by privilege, exile, and resilience. The son of a Czech diplomat, he carved out a singular path in animation — one marked by a distinct visual voice, a relentless work ethic, and a deep emotional honesty.

From a modest home studio in Penn Wynne, Pennsylvania, Fierlinger worked with his wife and creative partner, Sandra Schuette, producing films that felt deeply personal even when they were commissioned by corporations. Schuette was far more than a collaborator — she was his anchor, steadying him emotionally while also contributing artistically. Their partnership, both in life and in work, was central to the second half of his career. Together, they created films that pushed animation toward documentary, introspection, and philosophical reflection.

Fierlinger’s work earned him numerous accolades, including three Peabody Awards. He won these prestigious honors for Still Life With Animated Dogs (2000) and A Room Nearby (2003), both of which explored deeply human themes of loneliness, isolation, and emotional resilience. These works were celebrated not just for their innovative animation but for their ability to capture profound human experiences through animation.

He was also nominated for an Oscar for It’s So Nice to Have a Wolf Around the House, further cementing his place in the world of animation and film. But it was “Teeny Little Super Guy,” the beloved segment he created for Sesame Street, that became one of his most iconic contributions to children’s programming. The tiny, plucky superhero drawn on a plastic cup became a standout character and was adored by generations of young viewers. Fierlinger’s work for Sesame Street continued for decades, as he contributed numerous educational segments on letters, numbers, and more, leaving an indelible mark on the show’s legacy.

Throughout his career, Fierlinger balanced the demands of commercial work with an indie sensibility, creating films that were distinctly his own. Whether he was animating for a corporate client or crafting deeply personal narratives like Drawn From Memory, his style remained unmistakable: fluid, sketchy drawings reminiscent of James Thurber and Saul Steinberg, set in gently saturated palettes. His themes — nostalgia, memory, personal history — threaded through everything.

At a glance, his films can appear sentimental, even quaint. But like the work of Norman Rockwell or Frank Capra, they carry emotional weight not because they reflect the world as it is, but because they offer a version of it we might yearn for. His animation is a portrait of domestic kindness, imagined community, and human vulnerability. In cynical times like these, such visions risk seeming naive. Yet they speak to something deeper: a shared longing for connection, dignity, and safety in the everyday.

But behind this idealized world stood a man who was fiery, outspoken, and sometimes difficult. Shuffled between countries as a child, largely overlooked by his parents, Fierlinger grew up isolated and unsure of where he belonged. That estrangement never quite left him, and his honesty, shaped by hardship and recovery, often rubbed others the wrong way. Still, beneath the prickly exterior was a fiercely intelligent and empathetic soul who saw more than most gave him credit for.

Early Years

Born Pavel Fierlinger in Japan in 1936, his family moved to the United States as a toddler. He was raised in Burlington, Vermont, in relative material comfort but emotional solitude. “I didn’t have parents so much as caretakers,” he once said. Socially awkward and unathletic, he found refuge in drawing. It became both his shield and his language.

At 11, his family returned to Czechoslovakia. It was there that he created his first animation, a flipbook sequence shot with his father’s Bolex camera. The spark was immediate: “The moment I saw my drawings move, I was hooked.”

He studied animation at the Bechyně School of Applied Arts and later served in the military, where he continued to animate. Despite the oppressive climate of Communist Czechoslovakia, Fierlinger managed to launch the country’s first independent animation studio, AKF Studio. This was no small feat. At a time when owning a typewriter required a permit and film stock was state-controlled, television’s rise and the availability of 16mm film gave him a narrow path to work within. “Because I was a member of the artists’ union, I was allowed to work at home,” he said. “The animators at the Czech state studio were shocked.”

Between 1958 and 1967, he created nearly 200 shorts, mostly for children and television station breaks. These early works carried a sly defiance, a testament to a man working around the system while quietly shaping a career that would eventually span continents.

Escape and Reinvention

In 1967, Fierlinger fled Czechoslovakia to Holland, where he worked briefly for Dutch television before moving on to Paris as a spot animator for Radio Télévision France. He then traveled to Munich, where he worked as a key animator on a feature film.

To ease his labor in exile, Fierlinger had developed a unique style in Prague, using non-permanent magic markers. “If you used it on a plate, you could make a line and then smudge it a bit. All I needed was a ceramic tile, and I would do this under the camera.” This technique worked well, but there was a challenge — where could he put the camera? With so little space to work with, he had to improvise: “I’d put the camera on a tripod, then put a table against the wall and place the tripod on the table. I was between the legs of the tripod, with my back to the wall. I put one light to shine on the stand.” This mobile studio allowed Fierlinger to work quickly while maintaining consistency in his style.

The United States and Sesame Street

In 1968, the now-married Fierlinger briefly returned to New York, where he did some documentary work for Universal Studios. In 1969, with a son in tow, the family settled in Philadelphia, where Fierlinger remained for the rest of his life. He worked with Concept Films, a company that created political commercials for Hubert Humphrey and other candidates. He stayed with Concept for a year-and-a-half but soon realized that Philadelphia, lost in the smoky shadows of the Big Apple, offered little work in animation. Despite the new family, these years were a period of struggle and loneliness for Fierlinger.

In Czechoslovakia, the art community had been very close-knit; artists drank together, argued, talked, and shared. There was no such community in Philadelphia. Then again, Fierlinger was not the most likable fellow and, horror of horrors, he was a commercial artist.

In 1971, Fierlinger found much-needed support in the form of Dave Connell, an executive at the Children’s Television Workshop. Connell commissioned Fierlinger to make a variety of short films for both Sesame Street and The Electric Company. Fierlinger also ended up creating one of Sesame Street’s most popular series, “Teeny Little Super Guy,” for Sesame Street.

“Teeny Little Super Guy came out of insecurity. I wanted to make a series. I needed a series. I needed a steady flow of work, but Dave said that I was too small and that I couldn’t produce fast enough.” Fierlinger took a plastic cup, drew on it, and surrounded the character with other household objects. “It’s like a cel, and you can draw on it. You can pre-fab all the steps. Then we set up scenes with everyday household objects.” Connell liked the idea, and Jim Thurman (a long-time Fierlinger collaborator) wrote the first stories. “Then they trusted me.”

“Teeny Little Super Guy” received some of the highest ratings from test groups, and Fierlinger made thirteen installments. He was surprised that he was not asked to produce more, though he produced many other projects for Sesame Street, and in the end, the experience at Sesame Street turned out to be a great asset. “It’s got me work. Clients don’t want Sesame Street, but they know you are a good animator if you worked there.”

While working for Sesame Street, Fierlinger founded his own animation company, AR&T Associates (Animation Recording and Titling Services). Nestled in the Philadelphia suburb of Penn Wynne, AR&T produced an astounding 700 films, commercials, and IDs in its twenty-nine-year history, including a lot of work for health care and corporate clients.

The most notable film of AR&T’s early years was It’s So Nice to Have a Wolf Around the House (1979). The film was commissioned by the Learning Corporation of America (LCA) and was based on a book by the same name. Voice actor Jim Thurman ad-libbed the entire film. “We had no script; [Thurman] just looked at the pictures on every page and said something, so we pretty much made things up as we recorded.”

In the film, an old man living with his old cat, old dog, and old fish decides to look for a ‘charming companion.’ The companion arrives in the form of one Cuthbert Q. Devine. Owing to the man’s poor eyesight, Cuthbert, a wolf, is hired. The flamboyant wolf instantly brings life into their stagnant lives; he cooks, cleans, paints, and entertains the tired souls. Paradise falls, however, when it is revealed that Cuthbert is actually a wolf. Eventually, the companions learn that appearances are not important, and in turn, they learn to become more independent.

While the film is somewhat dated, it clearly marks the first signs of Fierlinger’s distinctive style. The thick black lines, dark, warm colors, and the strong, confident voice of Jim Thurman are evident. In content, Wolf is a tale of everyday folk, little voices that Fierlinger would amplify throughout his career.

Wolf went on to receive a number of festival awards and was nominated for an Academy Award. Once again, success was not kind to Fierlinger. “After I got the Oscar nomination, I never heard from LCA again.”

Art and Survival

Despite working within commercial constraints, Fierlinger infused many of his commercial pieces with personal detail and tonal complexity. His best-known commercial work came in the 1980s and ’90s through pieces like The Quitter, We Sure Know How to Pick ‘Em, and I’ll Be There, each using humor or intimacy to approach heavy themes like addiction, fatherhood, and loss.

But by the late Eighties, Fierlinger was unraveling personally. Drinking heavily, clashing with collaborators, and alienated from loved ones, he finally hit bottom in 1989. A commission to create a film about alcoholism (And Then I’ll Stop) became the catalyst for his sobriety. Using audio from real recovery interviews, the film ends with Fierlinger’s own voice narrating his descent and recovery — a raw, unflinching moment that remains one of animation’s most powerful autobiographical sequences.

Drawn From Memory

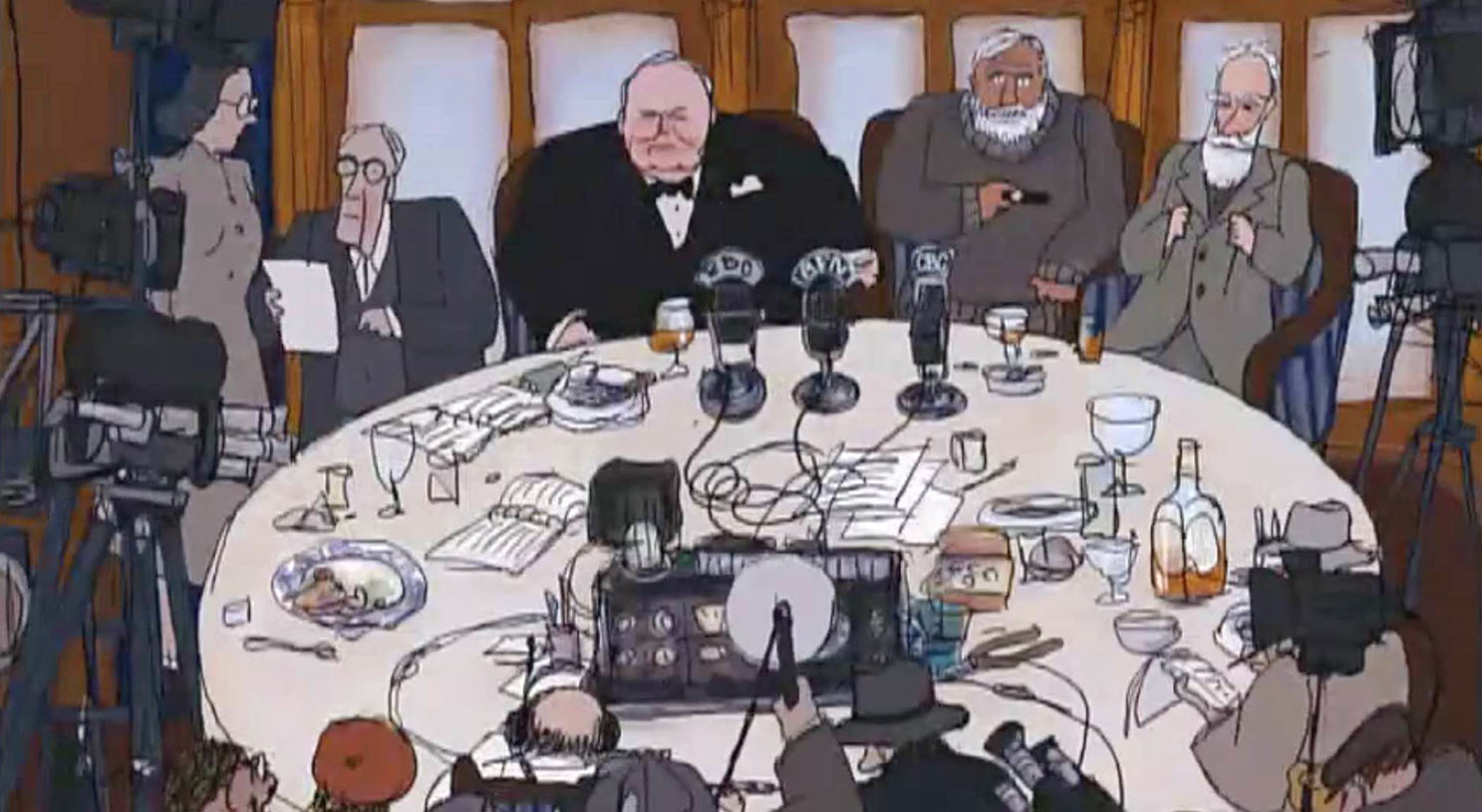

Drawn From Memory (1995), his most ambitious work, was both autobiography and reckoning. Originally imagined as a political chronicle, it evolved into a fierce portrait of a toxic father-son relationship, colored by the traumas of post-WWII Europe.

Animating his father, Jan, frame-by-frame, became a strange catharsis. “He never wanted me to be an animator. So I brought him to life and did what I wanted.” Sandra’s presence here was crucial, both in visual contribution and emotional grounding. Her input helped soften some of Fierlinger’s sharper edges, offering visual warmth to even the darkest memories.

The film, while often called “forgiving,” is anything but gentle. It’s honest, often brutal, and in its final moments, turns inward: Paul asking for the forgiveness he never gave his own father.

The Domestic Turn

In the 2000s, Fierlinger and his wife began exploring everyday life and emotion through deeply personal shorts. Still Life With Animated Dogs (2000) reframes Fierlinger’s life through his dogs, loyal companions who gave him the stability people often hadn’t. “They make you feel important,” he said. “They teach you to survive.”

Then came A Room Nearby (2003), where the couple blended interviews with visual interpretation to explore loneliness and hope. In one segment, Milos Forman reflects on the grief of losing a beloved dog. In another, a man finds peace in realizing he’s just “another speck of stardust.” The animation, set to John Avarese’s music, is whimsical, haunting, and unsparing.

These later works, shaped so intimately by Sandra’s steady influence, revealed a softer, more contemplative Paul, one willing to share the stage, even the spotlight.

In 2009, the Fierlingers released My Dog Tulip, an adaptation of J.R. Ackerley’s memoir, featuring voice work by Christopher Plummer and Isabella Rossellini. It was Paul’s last major film, a love letter to the loyalty and messiness of dogs, life, and everything in between. The film screened at Annecy, won special mention in Ottawa, and took the grand prize for best feature at Animafest Zagreb. (In 2018, he was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Zagreb festival organizers.)

Chris Sullivan, an independent animator (Consuming Spirits) and a teacher at the Art Institute of Chicago, reflected on Fierlinger’s impact:

His work has inspired me and many around me in its insistence and roughness. He just moves forward — each frame can be beautiful and painterly or a quick sketch. In that, there’s a sense that someone is truly speaking to you, without the need to dazzle or refine. It is raw expression. He always described his work as ephemeral, and immediately in the past. I find this wonderfully refreshing.

Producer and director Richard O’Connor (Ace & Son Moving Picture Company), who originally hailed from Philadelphia and remembered seeing many of Fierlinger’s commercials on local TV, shared: “The only fan letter I’ve ever written was to Paul Fierlinger. When we met a few years later, he didn’t pretend to remember — or to care. Maybe that’s what made his work extraordinary: the unwavering focus on telling his story.”

In the end, Fierlinger’s films told the story of a man trying to make sense of the world — and of himself. Through hand-drawn lines and gentle humor, he mapped loneliness, redemption, and love, both the kind we lose and the kind we’re lucky enough to keep. He leaves behind a body of work that is emotionally vivid, visually distinct, and profoundly human.

Many of Fierlinger’s films can be seen on his Vimeo channel.

Pictured at top: Teeny Little Super Guy, My Dog Tulip.