Belgian Animation Master Raoul Servais, Director Of Palme d’Or Winner ‘Harpya,’ Dies At 94

Belgian filmmaking legend Raoul Servais passed away on March 17 at his home in Leffinge, Belgium. The animated short films he created over a 60-year period earned global acclaim, including top prizes at Cannes, Venice, and Annecy, and made him a national hero in his home country.

Servais was born on May 1, 1928, in the seaside town of Ostend, Belgium, just a few miles away from where he passed away. A happy childhood was interrupted at the age of 12 when Germany invaded Belgium in May 1940. Servais’ father, who had been drafted into the military, was taken as a prisoner of war, and his family’s home and business were both destroyed, leaving the Servais household homeless and penniless.

Memories of World War II had a lasting impact on Servais and informed his approach to filmmaking, which often warned of intolerance and authoritarian ideologies. “I deal with various themes, but what they all have in common is mankind, his longing for freedom, peace and justice,” he once told an interviewer. “ I have always tried to emphasize the dangers which threaten humans.”

Following the end of World War II, Servais enrolled into the fine art program at Royal Academy of Fine Arts (KASK) in Ghent. He spent most of his twenties as a struggling artist, taking whatever work he could find to support his wife and two children. He worked odd jobs – from dishwasher to longshoreman to factory worker to graphic designer – while continuing to develop his skills as a painter and fine artist. He was among six painters hired to paint an oversized mural designed by Belgian surrealist René Magritte, and though Magritte fired Servais after an argument over technical issues, they later reconciled and Servais was allowed to finish the job.

He tried his hand at producing live-action shorts and experimental films during this period. Animation was in the back of his mind too, but the lack of technical resources and know-how prevented him from completing animated films. Despite several attempts to produce animation, Servais didn’t finish his first professional animated film, Harbor Lights (1960), until the age of 32.

In 1963, Servais was invited to set up an animation school at his alma mater, KASK. At the time, no animation schools existed in mainland Europe, and the only way to learn the craft was through a studio apprenticeship. “We can say that in Europe, it was totally disconcerting to enter a studio,” he recalled. “What happened in there was almost ‘top secret.’” At one point, while still trying to learn animation, Servais had pretended to be a journalist and visited several companies, including Ray Goossens’ studio in Antwerp and Paul Grimault’s studio in Paris, so that he could see how the films were made, but his undercover attempts never got him any closer to understanding animation production.

Servais would oversee KASK’s program for decades afterward. The school ensured that future animation filmmakers wouldn’t struggle for equipment, knowledge, and resources as Servais had. Students could now learn the basics of animation in mere months, rather than the years it had taken Servais – and they wouldn’t have to pose as journalists to acquire the information.

One of his students at KASK in the 1970s was Paul Demeyer, who has since gone on to direct Rugrats in Paris and episodes of Duckman and The Rocketeer. Demeyer who would become a friend of Servais, remembered him as a teacher:

He was very systematic, something I later recognized as his way of working. We students were rather intimidated by his presence. He was quite formal, not necessarily in his appearance, which was always a blue jeans suit and a little hat, but in his calm demeanor and his reflected way of speaking. Balanced and at ease, always attentive and present, almost like a monk. He was not the kind of teacher who joked around, or tried to be liked by the students, he was just himself.

Servais hit a stride in the 1960s, and between 1963 and 1973, he directed eight animated shorts, including Chromophobia (1965), a deceptively cheerful-looking allegory about a fascist regime that sucks the color out of society, and Operation X-70 (1971), which he created as a response to seeing images of the American military gassing the Vietnamese. “I decided to produce a parody of the war,” says Servais of the latter film. “It was my way of expressing my horror, of protesting against the violence.” Servais’ films were well received at international festivals, winning dozens of awards, including first prize at the Venice Film Festival (Chromophobia) and a special jury prize at Cannes (Operation X-70).

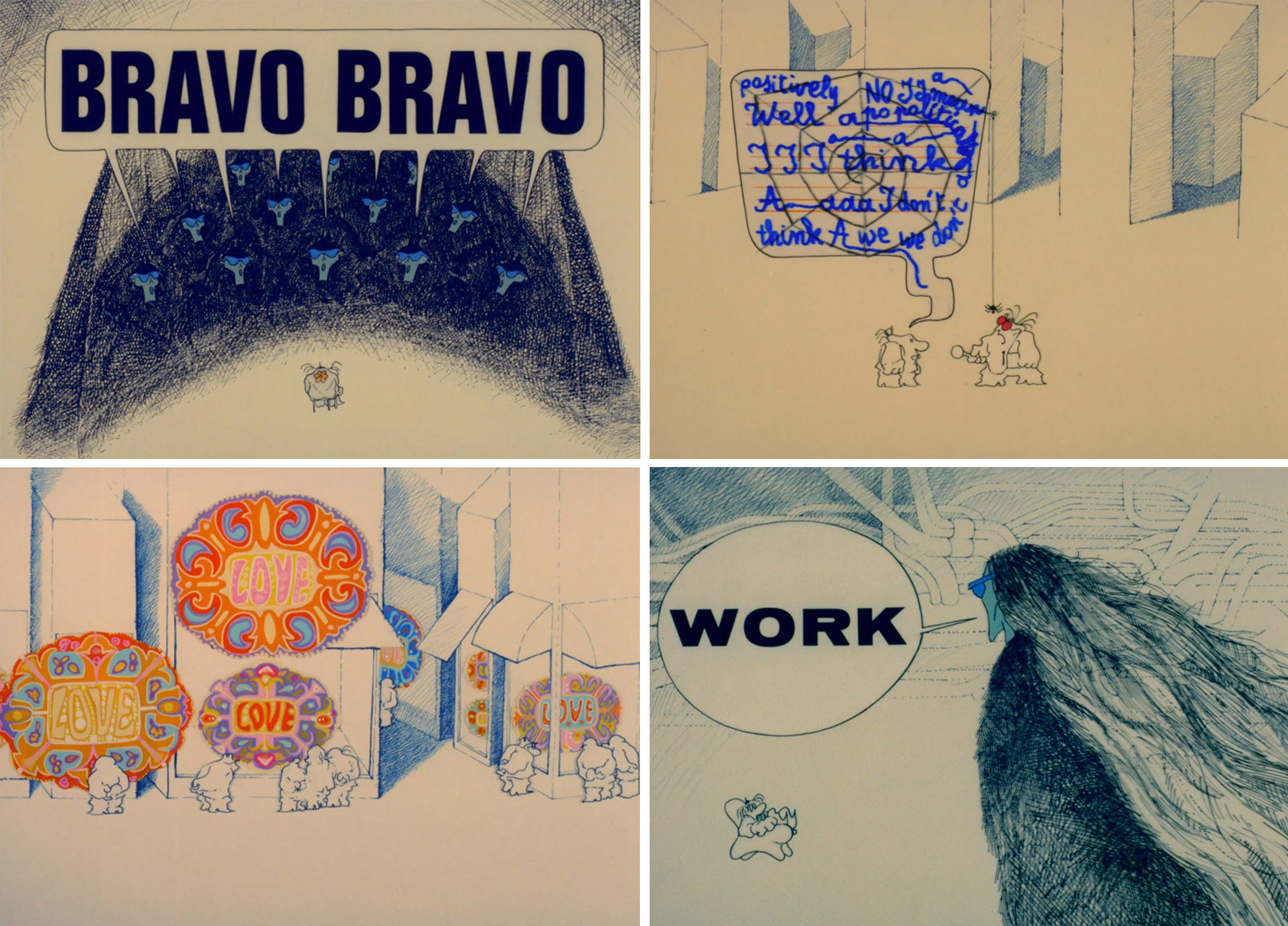

Servais was always in conversation with contemporary culture and art around him. Goldframe (1969) is a satire of Hollywood hubris, while To Speak or Not to Speak uses comic speech bubbles and Pop Art elements in its exploration of, in Servais’ words, “the manipulation of the individual, which exists in an aggressively capitalist world of money as well as in a fascist, militaristic world.”

Another film, Pegasus (1973), about man’s fear of being replaced by technology, references Flemish expressionists such as Constant Permeke, Gustave De Smet, and Frits Van den Berghe. Servais said that using these artists as inspiration was an easy choice: “I couldn’t comprehend why people were so keen on imitating Hollywood. Why not use our own graphic tradition, our own personality?”

The varied graphic styles and visual techniques that Servais employed in his films led one film critic to observe, “We could say that every film by Servais is not only an anti-Disney film, but also an anti-Servais film, in so far as he refuses to repeat itself.” Nowhere is this truer than Harpya (1979), a standout example of animated horror that uses a hybrid technique of live actors combined with optical and animated effects. The film was a remarkable success, earning Servais the Cannes Palme d’Or for short film and cementing his reputation as a major force in European animation.

One filmmaker who was impressed by Harpya was future Pixar creative chief John Lasseter. He recounted a story to me while I was writing The Art of Pixar Short Films that took place in the mid-1980s. Lasseter was presenting animation tests of a Luxo lamp at an animation festival in Belgium. Servais, who was in attendance, asked him afterward about the film’s story. Lasseter said that the film didn’t have a story; it was just a character study. The answer left Servais unsatisfied, and he told Lasseter that a piece of animation, no matter how brief, must have a story with a beginning, middle, and end.

While Servais’ own work could be ambiguous and open to interpretation, his comment to Lasseter told of his own approach to filmmaking. Servais’ films might not have followed the conventional narrative beats of Hollywood (which, incidentally, is likely why he was never nominated for an Oscar), but he nevertheless placed a strong value in storytelling and communicating with audiences through his artwork. Lasseter took Servais’ advice too and developed those animation tests into Luxo Jr. (1986), the iconic two-minute film that would serve as a calling card for the fledgling Pixar.

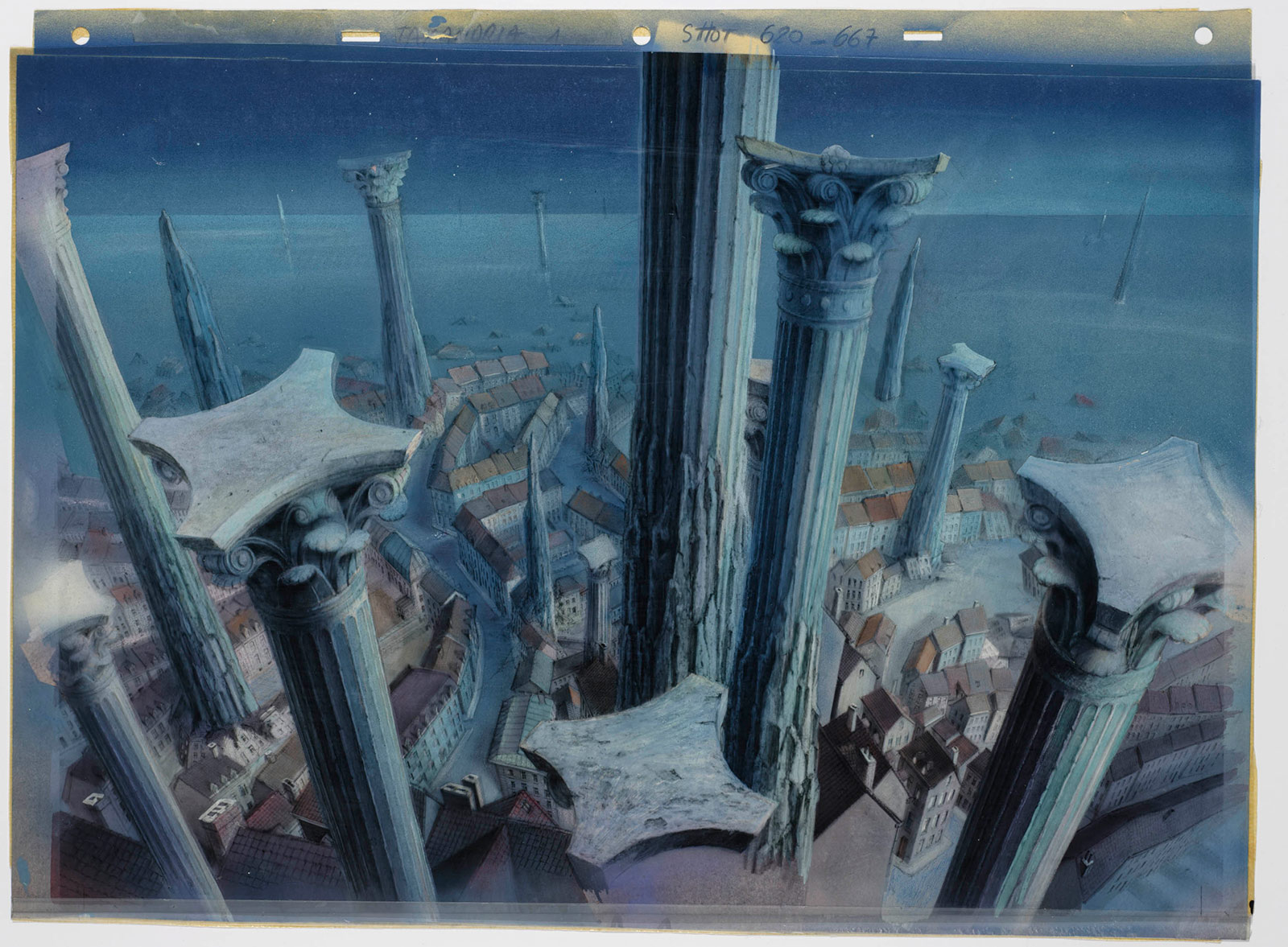

Following Harpya, Servais didn’t release another film for 15 years. When he did, he surprised everyone with the feature-length Taxandria (1994), a fantasy about a totalitarian regime that has banned the concept of time. An ambitious but flawed film, the years-long production and post-production didn’t go as he’d envisioned. He battled with producers over the film’s script, which was reworked repeatedly by different writers, and he could never convince the financial backers to fully embrace his vision for a hybrid film, so the film ended up being mostly live action. Although the experience was a personal and financial disappointment for Servais, the film holds an interesting spot in his oeuvre as the only long-form work he created, while also being notable for its use of early digital compositing techniques. Simultaneous to the production of the film, Servais also served as the president of ASIFA, the International Animated Film Association, between 1986 and 1994.

Servais returned to form in 1998 with Nocturnal Butterflies, a short film that was a tribute to Belgian surrealist painter Paul Delvaux and which earned Servais his first grand prix at Annecy. The hybrid film was made using a patented technique called Servaisgraphy that he had originally developed for Taxandria and which made it possible to blend live actors with animation techniques. With the advances in digital compositing though, the laborious Servaisgraphy technique was never used beyond this film.

Servais continued to make films until the end of his life . His last film, The Tall Guy, was released in 2021. In later years, Servais was the recipient of countless honors and exhibitions dedicated to his films. A major 2021 retrospective in Belgium, entitled “Raoul Servais: Between Magic and Realism,” has made its catalog available for free HERE and it contains detailed information about Servais’ life and work for anyone interested in learning more about him.

François Schuiten, the Belgian illustrator who curated “Between Magic and Realism” and was also a key creative collaborator on Taxandria, reflected recently on the qualities that make Servais’ work timeless:

The fact that he never made any concessions. His work is extremely pure, true to the intentions and convictions of its maker. Raoul doesn’t do whatever it takes to please. He approaches everything with meticulousness and rigor. His creations are sober: no part of them is accidental, everything has meaning. And the concept of time in his oeuvre is unlike any other. Time in Raoul’s films often stands still, is infinite, or lasts for all eternity. Taxandria existed outside of time entirely. Raoul kept reinventing that film, re-editing it over and over, until I could no longer see the film itself – only all the different films he’d woven into it over time.

Pictured at top: Harpya (1979).